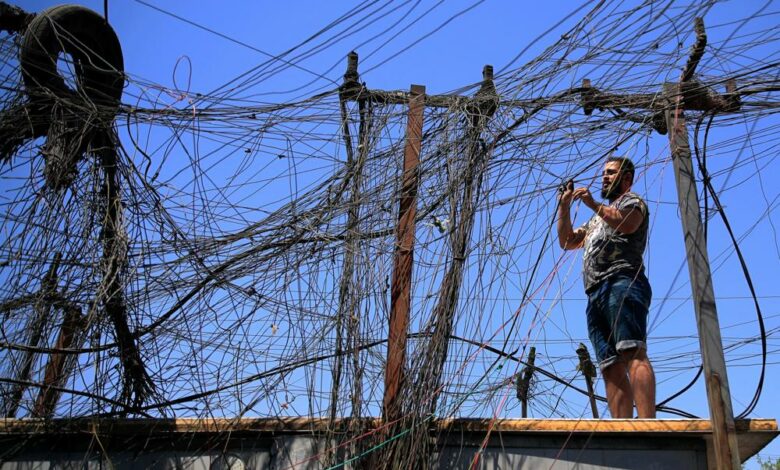

BAGHDAD (AP) — In the Baghdad suburb of Sadr City, glossy election campaign posters are plastered alongside jungles of sagging electrical wires lining the alleyway to Abu Ammar’s home.

But his mind is far from Iraq’s Oct. 10 federal election. The 56-year-old retired soldier’s social welfare payments barely cover the cost of food and medicine, let alone electricity. Despite chronic outages from the national grid, Abu Ammar can’t afford a generator.

When the lights go off, he has no choice but to steal power from a neighbor’s line. He doesn’t have the right political connections to get electricity otherwise, he says, a frail figure seated in a spartan living room.

In this country, if you don’t have these contacts, “your situation will be like ours,” Abu Ammar says.

In Iraq, electricity is a potent symbol of endemic corruption, rooted in the country’s sectarian power-sharing system that allows political elites to use patronage networks to consolidate power. It’s perpetuated after each election cycle: Once results are tallied, politicians jockey for appointments in a flurry of negotiations based on the number of seats won. Ministry portfolios and state institutions are divided between them into spheres of control.

In the Electricity Ministry, this system has enabled under-the-table payments to political elites who siphon state funds from companies contracted to improve the delivery of services.

The Associated Press spoke to a dozen former and current ministry officials and company contractors. They described tacit partnerships secured through intimidation and mutual benefit between ministry political appointees, political parties and the companies, ensuring that a percentage of those funds end up in party coffers. All spoke on condition of anonymity because they feared reprisal from political groups.

“Corruption occurs as an individual act or for political interest,” said ministry spokesman Ahmed Mousa. “It happens everywhere in Iraq, not just the Electricity Ministry.”

Meanwhile, the public seethes, outraged that in Iraq, a major oil-producing country with plentiful energy resources, the prospect of electricity 24-hours-a-day is a distant dream. Neighborhoods nationwide face daily outages — up to 14 hours during peak summer in the impoverished southern provinces, where temperatures can reach 52 degrees Celsius (125 Fahrenheit).

It’s a conundrum that baffles energy experts.

“The technical solutions are clear, and it’s not happening. One has to ask why?” said Ali al-Saffar of the International Energy Agency.

SHADOW CONTRACTS

In June, an Iraqi businessman received a call from the representative of the economic committee of the Sadrist Movement led by Muqtada al-Sadr, a populist Shiite cleric with a cult-like following whose party garnered the most seats in the 2018 election.

The representative, Abbas al-Kufi, wanted to see him. He had been informed the businessman met with Electricity Ministry officials to discuss a multi-million-dollar project to increase languishing tariff collections — bills owed to the government by consumers, which in Iraq are rarely paid.

At al-Kufi’s office, the businessman was instructed to deliver 15% of earnings, in cash, once the deal was inked and the ministry paid out the invoices.

“He told me, ‘The Electricity Ministry belongs to me, to my party,’ and I can’t do anything without his approval,” the businessman recalled being told by al-Kufi, who wields untold influence cemented by the Sadrist Movement’s powerful militia arm.

“They aren’t shy,” the businessman added. “They tell you: ‘If you don’t follow us, we will hurt you.’”

Al-Kufi, once a militia figure in the fight against the Islamic State group, is the latest example of party economic representatives who have strong-armed companies over the years.

Through coordination among ministry loyalists, company officials and lawmakers, representatives like al-Kufi are appointed to ensure certain contracts are approved, a contractor of their choosing is selected to execute them and a cut delivered to the party, according to officials at six companies involved in the process since 2018.

Al-Kufi was named in the local media in July when a letter purportedly penned by former Electricity Minister Majid Hantoush accused him of undermining the ministry’s work. Hantoush, who later resigned, denied writing it.

Nassar Rubaie, the head of the Sadrist Movement’s political wing, said his party earned the electricity ministry because it won the most parliament seats in the 2018 election. The ministry, with its high state budget, is among the most sought after. He confirmed al-Kufi was a Sadrist figure, but denied the allegations against him or the Movement, saying they amounted to “slander.”

If documents exist proving the complicity of Sadrist officials, he would personally see to it that they are prosecuted in a court of law, al-Rubaie added.

Only, no such paper trail exists.

Contractors said intimidation is standard operating procedure in the Electricity Ministry. One official from a major multinational company said he was ordered to subcontract to a local company exclusively as a package of deals worth billions was being negotiated with the government.

“It was made clear to me: ‘Either you join us, or you will get nothing in the end,’” he said.

To secure the funds for payoff, sometimes more expensive materials are invoiced than what is actually bought. One official estimated “billions” have been lost to these schemes since 2003, but accurate figures are not available.

Officials who question why contract prices are inflated receive warnings, including one who objected to a power plant in northern Salahaddin province that was overvalued by $600 million. He got a call when it became clear he would not sign off on the deal, he said.

Be careful, he was told.

DAUNTING EQUATIONS

Every electricity minister since the 2003 U.S.-led invasion that toppled dictator Saddam Hussein has faced this daunting equation: Iraq should be able to produce over 30,000 megawatts of power, enough to meet current demand, but only about a half of that reaches consumers.

Poor infrastructure, inappropriate fuel and theft account for 40%-60% of losses, among the highest rates in the world. In the more impoverished south, heat, urban expansion and illegal dwellings put even more pressure on the aging grid.

Revenue collections are abysmal and subsidies astronomical. The ministry collects less than 10% of what it should in billings. In December, a parliamentary committee reported that $81 billion had been spent on the electricity sector since 2005, yet outages were still the norm.

That is partly to blame on politically appointed civil servants, especially director-generals of key departments, who wield the most influence in the ministry and are empowered to facilitate contract fraud, according to six former and current officials. Negotiations after the 2018 election involved at least 500 such posts. The Sadrist Movement was given the most — 200.

The future is bleak.

Demand is set to double by 2030, with Iraq’s population growing by 1 million per year. The International Energy Agency estimates that by not developing its electricity sector, Iraq has lost $120 billion between 2014-2020 in jobs and industrial growth due to unmet demand.

A HIGH PRICE

A hidden cost of Iraq’s power woes: Sleeplessness.

Uday Ibrahim Ali, a generator repairman, is routinely wakened for urgent fixes in Basra’s Zubair neighborhood. His clients beg him: They have children struggling to sleep in the suffocating heat. “Can I ignore them? I can’t,” he says.

In the summer of 2018, poor electricity service prompted protests in Basra that left at least 15 dead. A year later, mass protests paralyzed Baghdad and Iraq’s south, as tens of thousands decried the rampant corruption that has plagued service delivery.

Independent candidates drawn from the protest movement in Basra are making electricity a priority as they prepare for the elections. With temperatures going down in September, power cuts are less frequent. To avoid protests ahead of the elections, Iraqi officials also improved distribution.

In Baghdad, Sadr City is a front line in the electricity crisis. A bastion of the Sadrist Movement, Al-Sadr’s portrait hangs in almost every home.

Publicly, his movement supports a reformist agenda. Meanwhile, disillusioned Iraqis call for boycotting the elections. Expected low voter turnout will guarantee grassroots movements like the Sadrists win a large share of seats.

That’s because of loyalists like Mahdi Mohammed.

When the lights go out, the 60-year-old asthmatic douses himself with water and wheezes in the dark, barely able to breathe. The parties that came before the Sadrist Movement are to blame, he says, adding that he will vote for a Sadrist candidate.

He has more to say, but in that moment the electricity returns, lights come on and a gust of cool air strikes his face. He closes his eyes and looks up toward the heavens.

“Welcome, welcome,” he cries.