Angry demonstrations in Libya were sparked in response to an obscure film depicting the Prophet Muhammad as a pedophile, womanizer and criminal. The film was rumored to have been promoted by American pastor Terry Jones and possibly produced by Nakoula Basseley Nakoula, a Coptic Egyptian who holds American citizenship. The attack on the US Consulate in Benghazi, which happened several hours after the assault on the US Embassy in Cairo, started as a peaceful demonstration in the afternoon of 11 September. It quickly escalated to gun fire and rocket propelled grenade attacks led by armed groups resulting in the deaths of US Ambassador Chris Stevens and three staff members.

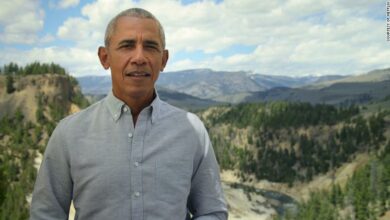

Calling the attacks “outrageous and shocking,” US President Barack Obama promised that “justice will be done,” but without indicating how or in what way. It seems clear that sophisticated military hardware will be used without due process to “neutralize” the perpetrators. Reportedly drones have already been deployed in Benghazi aerospace in order to track the instigators of this attack. Such decisions might make people across the United States feel comfortable, but the experience of using unmanned aerial vehicles in other areas where US forces are involved has not been conclusive; rather, they have nurtured more hatred and resentment toward US foreign policy in the Middle East as a result of heavy collateral damage among innocent civilians.

To translate his words into action, Obama immediately took military measures, such as expediting 50 Marines to reinforce the security of the US diplomatic mission in Tripoli as well as moving two warships to Libya’s coast, namely the USS Laboon and the USS McFaul, both of which are equipped with Tomahawk cruise missiles. Their display is less about establishing an authoritative maritime presence that exerts diplomatic influence by “showing the flag.” Rather, from a military perspective, the deployment of advanced naval surface fire support could be a prelude to “surgical” joint operations seeking to lead deep ground operations by US Special Forces.

The President’s response, however, appears to have become an electoral matter after his Republican opponent Mitt Romney accused him of “sympathizing” with those who carried out the attacks against the embassy. Republican allegations have reacted against the statement released on the evening of 11 September by the US Embassy in Cairo, which was stormed by protesters the same day. The American diplomatic mission pointed out that it “condemns the continuing efforts by misguided individuals to hurt the religious feeling of Muslims –– as we condemn efforts to offend believers of all religions.” The statement adds that “respect for religious beliefs is a cornerstone of American democracy. We firmly reject the actions by those who abuse the universal rights of free speech to hurt the religious beliefs of others.” Romney’s campaign was convinced that this statement was unjustifiably apologetic to the Egyptian protesters and Muslims before the attack against the US Consulate in Benghazi even occurred.

This statement was indeed a balanced one, more concerned about not offending more people in the Muslim world who saw this heinous film. Intelligently written, one can argue that it was not a typical reaction of the US government to such an incident; they are usually very “candid” about morally condemning those who are against the United States, but this statement was unusually concerned with the sensibilities of people in the region.

Insensitive and exploitative, Romney’s campaign tried to manipulate the unusual sensitivity of this statement to cast the president not only as a weak commander in chief, but also as sympathetic to the people who have been targeting American embassies. Given the nature of this rhetoric in an electoral context, it has become clear that this reaction is part of the Republican political calculus. Similarly, in 2010, the so-called ground zero mosque issue was basically a ploy to drum up Republican support for congressional candidates by playing on American values which they alleged were being threatened by Muslims, insinuating that they do not share the same values.

Seemingly, Romney is pursuing his dream of getting into the White House on the back of the death of US diplomats, as if it is ethical to base one’s own political fortunes at the expense of a religious minority.

Instead of each presidential candidate seeking political capital from this tragic event, it would be wiser to help Libya’s fledgling leadership end the security vacuum hat threatens state control and undermines regional stability. Libya’s state-building process will be an empty one without a robust commitment by external actors to support accountable, strong, professional and stable institutions, mainly security forces, the military and judiciary.

Elected on 12 September by the National General Congress (NGC), the new Prime Minister Mustafa Abushagur is aware that Libya’s credibility is at stake. Cultivating confidence with the country’s partners as well as the Libyan people will be the most difficult challenge he has to overcome. To this end, he has to distance himself from the apparent powerlessness of the previous government. The latter offered only fruitless condemnations for 11 months after the fall of Gaddafi’s regime as similar attacks were perpetrated in Benghazi against the International Committee of the Red Cross, the British Ambassador’s convoy, the Tunisian Consulate, and the US Consulate on two occasions, including on 11 September, not to mention the repeated desecration and vandalizing assaults on Libya’s Sufi shrines and Muslim scholars’ graves across the country. As yet, nobody has been apprehended or brought to justice for these criminal acts.

Abushagur’s government needs to take the imperative reinforcing security seriously. It includes, among other measures, a genuine demilitarization of armed groups, curbing militias seeking political power and retribution, effective procedures to control the proliferation of small and mid-caliber weapons across the country, strengthening a monopoly on the use of force by building security institutions based on citizenry rather than tribal and sectarian affiliations, empowering civil society as one of the main players in the security realm, and restoring democratic civil control over security services.

In the absence of a functioning security system, transitional Libya will not be able to provide Libyans with human security based on people’s safety, freedom and socioeconomic wellbeing, nor will it convince foreign investors to trust Libya’s market.

More than ever before, the new democratically elected Libyan government will be under scrutiny from its own citizens. Libyans who fought bravely for their freedom and dignity will never acquiesce to tarnishing their country’s image with useless violence in the name of Islam and its symbols.

Noureddine Jebnoun teaches at the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University.