Serbs and Kosovars want to take their borders back to the drawing board. Villages and valleys changing hands could help soothe an ancient feud but potentially break a longstanding taboo.

The sanctity of state borders is a jewel in the crown of European state law. In theory. The redefining of boundaries along ethnic-cultural lines in Bosnia and Herzegovina 20 years ago passed without consequence.

The drawing up of borders, in this case, was done in the aftermath of bloodshed. Now Serbia and Kosovo are gearing up to repeat history, but with one difference — they want to redefine their borders amicably between themselves.

The terms of the trade remain vague, but the deal seems done nevertheless. It is a risky endeavor for the two states, and for the region as a whole.

A territory-swap meet?

Negotiations have been going on for more than seven years. But not in Belgrade and also not in Pristina — the bitter enmity between the two prevented that.

Instead, EU chief diplomat Federica Mogherini has been at the center of talks aimed at making the impossible possible.

The nitty-gritty of the deal is intriguing, and the EU’s integral principle of not shifting borders has been flipped on its head. That seems to be precisely the plan: Trade you some of yours for some of mine! It’s the antithesis of the longtime core EU ideal of stabilizing multinational societies and not slicing them up.

Kosovo is a de facto new state in Europe with only a small number of EU countries — where fears of ethnic secession also exist — still not officially recognizing it.

This gives Kosovo a powerful negotiating position that they could only have dreamed of10 years ago.

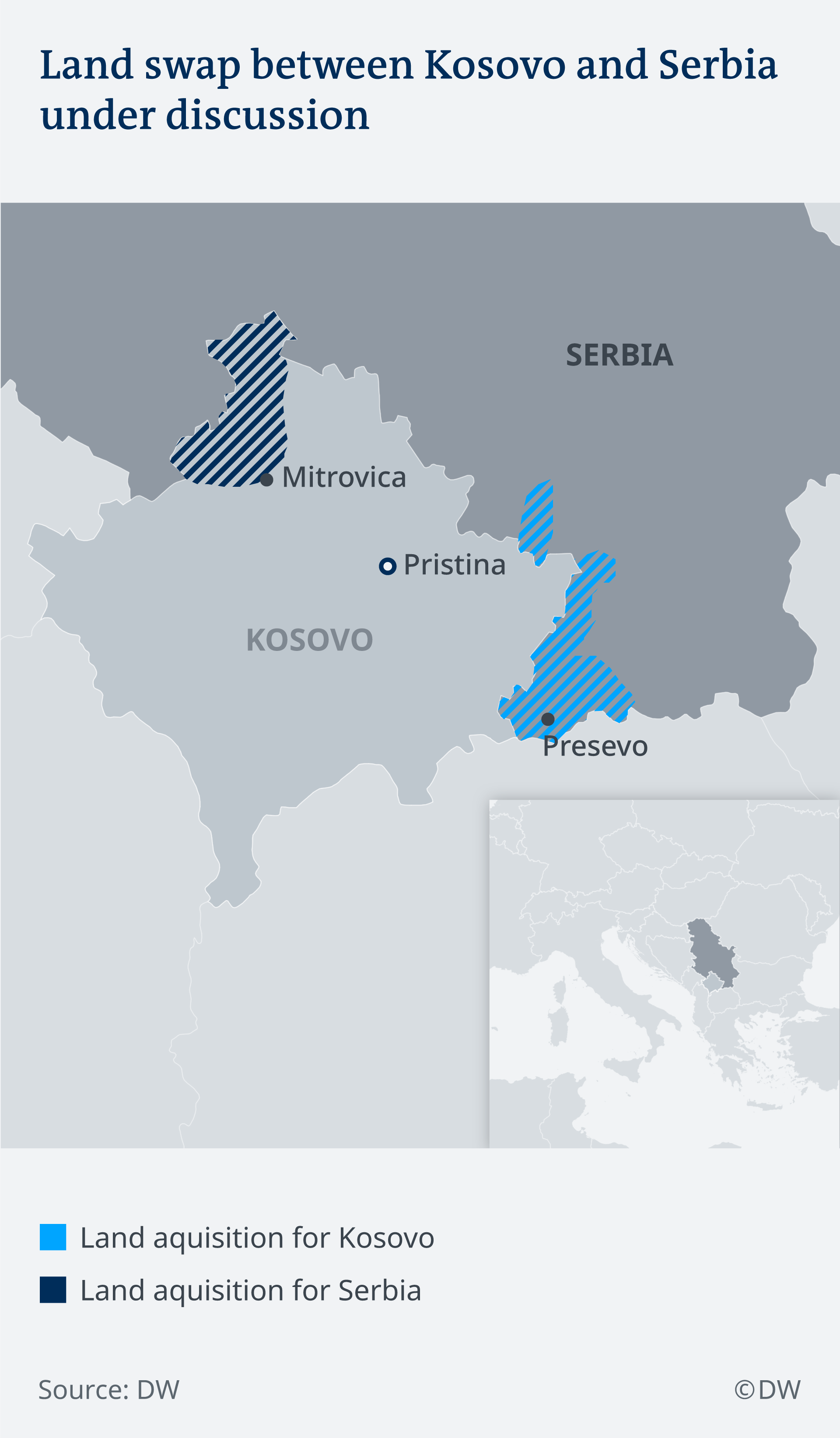

Pristina could be given the Presovo Valley, a predominantly Albanian area in southern Serbia. In return, Serbia would claim northern Kosovo, home to almost 45,000 Serbs.

But the ethnic makeup of the population is not the only factor at play in the territory swap. It is also about resources and cultural monuments. Economic interests motivate both sides, but the presumable loss of Orthodox churches and monasteries also fuels nationalistic sentiment among Serbs. Kosovo — with its legendary battleground, the Kosovo field — is regarded as the “cradle of Serbian culture.”

Myths, wars and prehistories

The Kosovo field, the medieval heartland of the Serbs, was lost bit by bit over the course of the Ottoman invasion of southeastern Europe.

The mythic qualities of the Kosovo field have been repeatedly exploited for propaganda, most notably in 1989. Slobodan Milosevic took hold of the then-Yugoslav province of Kosovo 600 years after Serbian forces faced Ottoman troops in the Battle of Kosovo.

It was the beginning of the end of Yugoslavia, and a course of history that would see a quarter of a million people lose their lives.

When the conflict in Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina finally subsided, the Kosovo-Serbian conflict escalated in the spring of 1998. The media reported on systematic mass expulsions of Albanians by the Serbs — many of which are documented, others were staged.

A marathon of negotiations followed. When talks broke down, NATO launched a bombing campaign of Serbian targets that lasted almost 80 days. Many civilians died in the intervention. As a quasi-international protectorate, Kosovo experienced a short transition period, which led to the declaration of independence on February 17, 2008 — of Europe’s youngest state.

Potentially risky consequences

If there were an exchange of territory between Serbia and Kosovo, it might open Pandora’s box in the Balkans states — at least legally. Other countries in the region might see similar debates reignited. How such an event might play out in the context of Bosnia and Herzegovina remains the most difficult part to predict.

Serbian hardliners in the Republika Srpska have never buried their plans to accede to Serbia; such ambitions have only ever temporarily been put aside. The same applies to Croatian nationalists in West Herzegovina who would pledge sovereignty to Croatia in a heartbeat. Macedonia and Montenegro are also multi-ethnic states.

Paradoxically, the politically and legally controversial trading of land brings both states closer to the EU. Both are among the six Western Balkan countries seeking to join the bloc in the mid-term, but still have to prove themselves.

The EU’s potential inclusion of the Western Balkan states is a divisive issue. French President Emmanuel Macron wants to establish a two-speed Europe of the “forward-looking,” and has his foot firmly on the brakes when it comes to enlargement. Others are keener to allow “problem cases” into the fold before they fall into the arms of China, Turkey or Russia.

Opponents and proponents

The list of supporters and opponents of the intricate plan is long — on both sides. Donald Trump’s security adviser John Bolton is now said to have given his blessing to the deal. How long that approving stance lasts is, however, irrelevant given Europe’s apparent lack of interest in new US foreign policies.

The German government, and Chancellor Angela Merkel in particular, is cautious. As is elder statesmen Carl Bildt, the former EU special envoy to Yugoslavia, and Wolfgang Ischinger, a key figure in the Dayton Peace Accord.

The former top Balkan expert and right-hand man of Richard Holbrooke in Bosnia, James W. Pardew, is also firmly opposed to the Kosovar-Serb border changes. Other critics include Christian Schwarz-Schilling, a onetime minister in Helmut Kohl’s cabinet and the EU High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2006 and 2007, as well as his British predecessor in the role, Paddy Ashdown.

But the political showdown is on. On September 9, Serbia’s President Aleksandar Vucic intends to deliver the “greatest speech of his life” in front of his compatriots at a rally in Mitrovica, Kosovo.

Vucic’s exchange offer in the lion’s den is also about the metamorphosis of a nationalist hawk into an EU-worthy European. Serbia wants to join the Brussels club — that is its priority. The grief over the partial loss of the “cradle of Serbia” is likely to be limited in Belgrade.