Controversy surrounds Saudi Twitter ads depicting Moroccan women for sale as domestic servants in the oil-rich kingdom. The case has highlighted the abuse of foreign workers in Saudi Arabia, but will either nation react?

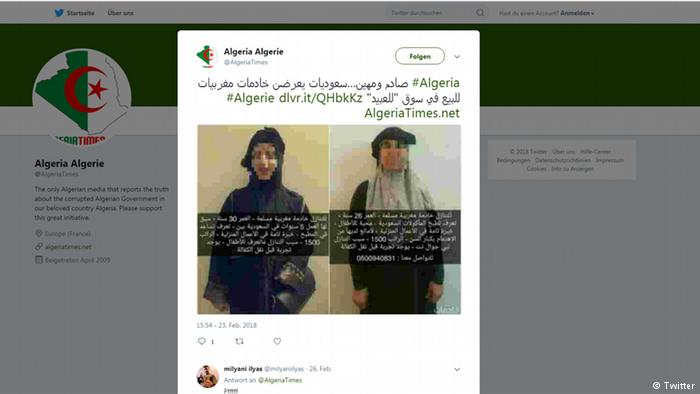

In Saudi Arabia, pictures of Moroccan women have been circulated on social media to be sold as housemaids for lump sums of cash. The Twitter picture above shows two Moroccan women being advertised for “sale” as a domestic worker. The woman on the right is described as being 30 years old, with five years’ work experience in Saudi Arabia, and knows how to cook and clean; she is offered for 1500 Saudi riyal (€325, $397). The woman on the left is described as “able to cook Saudi dishes and enjoys children.” She is also being offered for 1500 riyal.

The case is clear-cut: “This is an example of slavery,” Yasmine Ajoutat, a Moroccan blogger on women’s issues and human rights told DW. She explained that foreign women working as housemaids in Saudi Arabia are severely restricted in what they may do. For example, many Saudis do not allow their maids to own a cell phone to communicate with their families. In one ad the seller complains that they are selling a Moroccan woman as a housemaid due to “her ambition to obtain a mobile phone.” In another Twitter post, a passport of a Moroccan woman had been taken away and used to advertise the maid for sale.

Mistreatment and abuse are frequent

In Saudi Arabia, the women working as housemaids or domestic helpers are not just from Morocco, but from other developing nations such Ethiopia, India, and the Phillipines. Numerous cases have come to light in recent years of female domestics being mistreated. For example, Filipina maids in the kingdom have complained recently that they are being transferred from one employer to another without their consent, which leaves them vulnerable to abuse as the transfers are not covered by their contract. In October 2017, an Indian woman from Punjab working as a housemaid in the kingdom begged her government via video to save her as she claimed to have been denied food for days and been physically tortured.

Foreign maids and domestic servants work under the umbrella of the “Kefala” system, which is a legal structure in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries by which employers sponsor foreign workers and remain responsible for the visa and residence status of the women fur the duration of their stay in the country. The system has come under heavy criticism from rights organizations that object to the restrictive and even abusive relationships it sometimes creates between employers and employees. In some extreme cases, employers abuse their employees physically and mentally, withhold payment, take away their passports and may refuse to let them return to their home countries.

The advertisements have called further attention to other cases of mistreatment of Moroccan women in the kingdom. In 2015, for example, Moroccan Lamia Moatamid, who married a Saudi man, was raped by her husband and then was imprisoned after trying to report the crime. She made a direct appeal to Morocco’s King Mohamed VI to save her and was eventually released from jail a year later. In February 2017, a Moroccan maid was thrown out of a window by her Saudi employer. A video showing her strapped to a hospital bed after the incident was shared widely on social media. And in some cases the mistreatment is allegedly carried out by female employers: many Saudi women were outraged at the influx of Moroccans post-2011 due to fears that Moroccan maids would seduce their husbands, and some reports of violence have emerged charging Saudi women with abuse.

Saudi-Moroccan relations

Saudi Arabia began allowing Moroccan citizens to work as domestic servants there only in 2011. Saudi website Al-Youm reported in late 2017 that such jobs pay around 1200 to 1500 riyals monthly. “Moroccan women who go to Saudi Arabia, like many others, are able there to to earn more money than in their home country,” said Ajoutat.

Moatamid’s appeal to the king notwithstanding, on the whole “Morocco is not interfering in these matters in order to keep the relationship between the two countries stable,” Ajoutat explained. She said her government displays little interest in the issue of its citizens being exploited in Saudi Arabia.

Abdul Aziz al-Khamis, a Saudi journalist, pointed out the strong relationship between Saudi Arabia and Morocco and argued that the case shouldn’t be politicized. He said these cases of Moroccan women being offered for sale online run “contrary to both Saudi and International law.” The publication of these ads on public forums are prohibited by the Saudi Ministry of Information as being material that which would humiliate the individual.

“If the story is true, the perpetrators will be taken before the Saudi authorities,” Aziz al-Khamis continued. In 2015, the Moroccan Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation passed a proposal which puts a moratorium on granting permission to its citizens wanting to work as maids in the Saudi kingdom. The law will enter into force in December of this year.