Vladimir Putin is set to travel to North Korea for a two-day visit starting Tuesday, the Kremlin said, in the Russian president’s first trip to the country in more than two decades – and the latest sign of a deepening alignment that’s raised widespread international concern.

This is a rare overseas trip for Putin since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began in 2022 and a key moment for North Korean President Kim Jong Un, who has not hosted another world leader in Pyongyang – among the globe’s most politically isolated capitals – since the Covid-19 pandemic.

The closely watched visit is expected to further cement a burgeoning partnership between the two powers that is founded on their shared animosity toward the West and driven by Putin’s need for support in his ongoing war on Ukraine.

Following his visit to North Korea, Putin will travel to Hanoi Wednesday for another two-day trip, in a display of Communist-governed Vietnam’s ties to Russia that is likely to rankle the United States.

Putin’s trip to North Korea will have a “very eventful” agenda, his aide Yuri Ushakov said during a press conference Monday. Both leaders plan to sign a new strategic partnership, Ushakov said, with main events of the visit scheduled for Wednesday.

Ushakov insisted the agreement is not provocative or aimed against other countries, but is meant to ensure greater stability in northeast Asia. He said the new agreement will replace documents signed between Moscow and Pyongyang in 1961, 2000 and 2001.

“The parties are still working on it, and a final decision regarding its signing will be formed in the coming hours,” Ushakov said, according to Russian state media RIA.

Satellite imagery from Planet Labs and Maxar Technologies shows preparations for a large parade in Pyongyang’s central square. One image shows a grandstand being constructed on the eastern side of Kim Il Sung Square, the site where all major parades in North Korea are held. In an earlier image, taken on June 5, North Koreans can be seen practicing marching formations.

US national security spokesman John Kirby told reporters Monday the Biden administration wasn’t “concerned about the trip” itself, but added, “What we are concerned about is the deepening relationship between these two countries.”

The US, South Korea and other countries have accused North Korea of providing substantial military aid to Russia’s war effort in recent months, while observers have raised concerns that Moscow may be violating international sanctions to aid Pyongyang’s development of its nascent military satellite program. Both countries have denied North Korean arms exports.

Putin’s trip reciprocates one Kim made last September, when the North Korean leader traveled in his armored train to Russia’s far eastern region, for a visit that included stops at a factory that produces fighter jets and a rocket-launch facility.

It also comes as tensions remain high on the Korean peninsula amid heightened international concern about the North Korean leader’s intentions as he ramped up bellicose language and scrapped a longstanding policy of seeking peaceful reunification with South Korea.

South Korea fired warning shots on Tuesday after North Korean soldiers working in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating the two Koreas briefly crossed into the South, according to South Korea’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, the second incident of its kind in the last two weeks.

An ‘advancing partnership’

Kim last week hailed the future of the countries’ “meaningful ties and close comradeship” in a message to Putin commemorating Russia’s national day on June 12.

“Our people give full support and solidarity to the successful work of the Russian army and people,” Kim said, according to the official Rodong Sinmun newspaper.

In an article for the Rodong Sinmun newspaper published early Tuesday local time to coincide with the trip, Putin thanked Pyongyang for showing “unwavering support” for Russia’s war in Ukraine and said the two countries were “ready to confront the ambition of the collective West.”

He said the two were “actively advancing their multifaceted partnership” and would “develop alternative trade and mutual settlements mechanisms not controlled by the West, jointly oppose illegitimate unilateral restrictions, and shape the architecture of equal and indivisible security in Eurasia.”

The meeting comes just days after a summit of the Group of Seven (G7) developed economies in Italy attended by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, where Western leaders reiterated their enduring support for Ukraine and agreed to use profits from frozen Russian assets to back a $50 billion loan to the war-torn country.

It also follows a Kyiv-backed international peace summit over the weekend attended by more than 100 countries and organizations, which was meant to drum up support for Zelensky’s vision for peace, which calls for a complete withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukrainian territory.

Putin rebuffed those efforts a day ahead of the gathering by offering his own peace conditions, including the withdrawal of Ukrainian troops from four partially occupied regions and that Kyiv withdraw its bid to join NATO – a position seen as nonstarter by Ukraine and its allies.

Putin’s visit to North Korea is widely viewed as an opportunity for him to seek to bolster Kim’s support for his war – a goal that may be increasingly urgent as long-delayed American military aid for Ukraine comes online.

Last month, US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin told American lawmakers the provision of North Korean munitions and missiles, as well as Iranian drones, had allowed Russian forces “to get back up on their feet.”

Between August and February, Pyongyang shipped about 6,700 containers to Russia, which could accommodate more than 3 million rounds of 152 mm artillery shells or more than 500,000 rounds of 122 mm multiple rocket launchers, South Korea’s defense ministry said earlier this year.

Both Moscow and Pyongyang have denied such arms transfers, with a senior North Korean official last month calling such allegations an “absurd paradox.”

When asked about concerns that Russia is considering the transfer of sensitive technologies to Pyongyang in exchange for those goods, a Kremlin spokesperson last week said the countries’ “potential for developing bilateral relations” was “profound” and “should not cause concern to anyone and should not and cannot be challenged by anyone.”

Putin on the world stage

Putin last visited North Korea in 2000, his first year as president of Russia, where he met with Kim’s predecessor and late father Kim Jong Il.

His travel now to North Korea and then Vietnam comes as the Russian leader appears keen to re-establish himself on the global stage, chipping away at an image of isolation in the wake of his widely condemned invasion of Ukraine by drawing in like-minded partners.

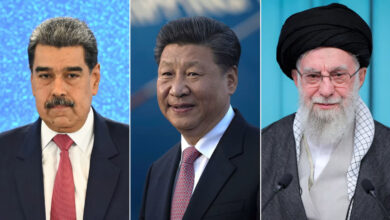

Last month Putin made a state visit to Beijing, where he and Chinese leader Xi Jinping made a sweeping affirmation of their shared opposition to what they see as a US-led world order.

Moscow last week hosted foreign ministers from countries including China, Iran, South Africa and Brazil for a meeting of the BRICS group of major developing economies.

US national security spokesman John Kirby on Monday called Putin’s latest travel a “charm offensive” following the leader’s re-election. Putin won his fifth term earlier this year in a contest without true opposition.

Putin’s move to bolster North Korean ties has also been a boon for Kim, who remains unbowed by years of international sanctions over his illegal nuclear weapons program.

The visit from a leader of a permanent member country of the United Nations Security Council will provide a signal to Kim’s domestic audience of his global clout – and a chance to push for deeply needed economic and technological support from Moscow.

Russia previously backed international sanctions and UN-backed investigations into North Korea’s illegal weapons program, which includes tests of long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles that could in theory reach the US mainland.

But Russia’s apparent increasing reliance on North Korea and rising frictions with the West appear to have shifted that dynamic. In March, Moscow vetoed a UN resolution to renew independent monitoring of North Korea’s violations of Security Council sanctions.

Additional reporting by Mariya Knight, Yoonjung Seo, Betsy Klein and Paul P. Murphy