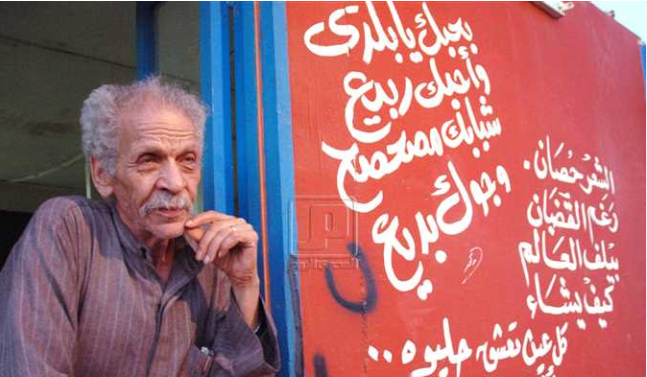

Last Friday at the premises of Prince Taz palace, (under the umbrella of the culture development fund) lyrics of renowned Egyptian poet, Fouad Haddad were sublime

In a spirit of social and political engagement, and with an original artistic twist, family and friends of late Egyptian vernacular pillar Fouad Haddad (1927-1885) gathered to remember him on Friday on the anniversary of his birth. Through the poetry evening titled Ail Al Maash, (A child in retirement) they commemorated the celebrated wordsmith by reciting his poetry and paying tribute to his vernacular wit.

Haddad wrote colloquial poetry throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s in an artistic trajectory that was seldom interrupted, even during his years of incarceration for political (communist) activism. At a time when art was often engineered by the state to promote its national project, Haddad opted to raise the flag of the emancipation of creativity.

Haddad’s overriding passion — alongside Salah Jahin, and later Abdul Rahman el-Abnudy and Sayid Higab — was the revival of colloquial Arabic-language poetry. It is a genre that does not necessarily belong to the folkloric tradition, which generally emphasizes the indigenous over the modern. Nor does it hold itself inferior to classical poetry, even though — in the realm of traditional Arabic language studies — the classical usually supersedes the colloquial.

Haddad’s quest was germane to everyday life — a sphere to which colloquial language is best suited. Through his poetry, he managed to look at issues of public concern through the lens of everyday experience.

For example, he used the well-known character of Al-Messaharati, whose job it is to wake the faithful for dawn prayers during the Islamic fasting month of Ramadan. In "Al-Messaharati" (1964), Haddad employed this character — engrained in society’s collective consciousness — to awaken in the reader notions of apathy and estrangement. Friday’s tribute included a recitation of "Al-Messaharati," which continues to resonate among 21st century audiences much as it did among those of the 1960s.

Imbued with a love for their ancestral homeland despite the difficulties of living in it, Haddad’s children and grandchildren established a dialectical relationship with their audience by posing the question: how can a contemporary sense of belonging materialize in the face of consistent alienation?

Throughout the poetry evening, Haddad’s son Amin performed solo recitals, followed by recitals by other presenters. These readings were interspersed with original compositions by Hazem Shahin, who performed them with his ‘oud alongside Ashraf Nagati and percussionist Amir Ezzat.

While Amin Haddad provided a rather traditional take on poetry recital, Samia Jahin and Ahmad Haddad added an element of performance art. Jahin — daughter of another father of colloquial poetry, Salah Jahin — articulated her words powerfully, while also adding subtle lines of satire here and there.

When Shahin began his musical accompaniment, the group burst into euphoric song, led by the oudist’s enthusiastic vocals. Shahin challenged the limits of experimentation by giving a rap-like percussion accompaniment to Ahmad Haddad, while the latter performed "Al-Duktur Saad" ("Doctor Saad").

At one point, eight-year-old Amina Fahmy reminded the audience of Haddad’s celebrated children’s poetry, which manages to attain a depth transcending age and function. She gave a playful performance of "Belyatshu Sughayar" ("Little Clown"), following a rather ominous recital of "‘Atr al-Saeed" ("Southbound Train"), whereby she reintroduced notions of hope to an otherwise gloomy subject.

Modern Arabic literature scholar Marylin Booth has written extensively about the use of colloquial language in poetry as the "language of the self and the conscience” and the language that “creates and categorizes reality." Friday’s performance of Haddad’s colloquial poetic works served to emphasize these notions.

Experiencing poetic recitation as a collective act, performed with passion, gives a further dimension to its reverberation. A proof of its — and Haddad’s — continued relevance and poetic power today.