“Reflections on Islamic Art,” edited by Ahdaf Soueif, appears at a time when Islamic art is surging back into fashion.

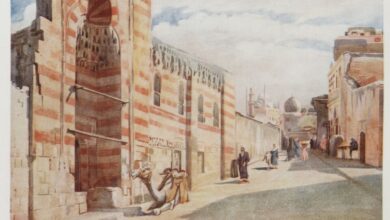

Soueif’s collection, published in November 2011, pairs art from Doha’s monumental Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) with creative writing from twenty-seven internationally acclaimed authors.

The MIA is a recent contribution to the world of Islamic art, having opened its doors in 2008. But it is not the newest addition: In November 2011, New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art opened a new permanent installation, the awkwardly but inclusively titled, “Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia.”

To coincide with its re-vamped collection of Islamic art, the Met also issued a new book of images and essays: “Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

The two publications — “Masterpieces” and “Reflections” — come at roughly the same time, both inspired by work in major museums. But the two projects are markedly different. “Masterpieces” is a coffee-table book, with beautiful images and “informative essays” about the history of Islamic art. Critic Maymanah Farhat, who reviewed the Met’s new installation for Jadaliyya, writes that the installation itself uses the old language of Orientalism, taking “great care to describe the ‘lavish,’ ‘sumptuous,’ and ‘superb’ qualities of these objects.”

The project of “Reflections,” on the other hand, is to shake off this language. The collection won’t give readers a crash course in Islamic art history. But it does offer poems, stories and essays that re-invigorate our understanding of Islamic art, Islam and art.

In her introduction, Soueif explains the idea behind “Reflections” through the email she sent to potential contributors: “‘The Museum,’ I wrote, ‘lends itself particularly well to the idea of this book — that there will be one piece that speaks to you, or a group of pieces that sets of a train of thought/feeling — and that out of this will come a response in words or images…Does this appeal?’”

For the project, Soueif chose a diverse range of excellent writers and thinkers, including art historian Oliver Watson, mathematician Marcus de Sautoy, scientist Jameel al-Khalili, filmmaker Sherin Neshat, philosopher Slavoj Zizek and Egyptian novelists Youssef Rakha and Radwa Ashour.

Each was allowed the freedom to engage with the museum in a way meaningful to them. Some had particular things they were looking for: Youssef Rakha wanted to see his beloved Sultan’s Seal, which is reflected in his latest novel of the same name; Radwa Ashour was looking for a penbox from Granada. Others found new-old things: Lebanese novelist Jabbour al-Douaihy discovered a portrait of the Saint Jerome that set off a series of childhood memories.

The collection ranges widely. But throughout, authors return to the idea of re-inventing the narratives of art and Islamic empire. Some authors, like Pankaj Mishra and Tash Aw, take a new look at Islam’s successes. Mishra comments on Islam’s “astonishing flexibility, its ability to adapt to new conditions” and the Malaysian Aw remarks on Islam’s multiculturalism: “No one told us that we were, in fact, part of a grand narrative of inclusiveness.”

Philosopher Slavoj Zizek goes farther still, re-writing a narrative of Islam as the “third way.” He writes: “Insofar as we tend to oppose East and West as fate and freedom, Islam stands for a third position which undermines this binary opposition — neither subordination to blind fate nor freedom to do what one wants, both of which presuppose and abstract external opposition between the two terms, but a deeper freedom: to alter or to choose our fate.”

Zizek also tries to re-invigorate our idea of art, reminding readers that these museum pieces were once part of daily life. Poet James Fenton, in his essay “A Great Carpet Fragment and a Great Carpet,” also addresses the relationship between life and art, noting that the proper way to view a great carpet is to stand on it.

Not all the essays are equally good. Palestinian writer Suad Amiry’s is a surprising disappointment. But most of the authors took their charge seriously, and were inspired not just to write beautiful creative work, but to shake off old ways of talking about Islam and art and to invent new ones.

As part of his essay, Egyptian poet and novelist Youssef Rakha dreams a conversation with Abdulhamit II in which the two share a handshake and a cigarette. Rakha examines the shorthand with which contemporary Islam has been identified — “beard, burqa, and bomb” — and goes on to imagine another path. He rejects the Anglo-European path of “integration into the rat-race of smoke-free capitalism” and notes that the way forward might just be through Islamic art.

He writes: “Reason, science, and art are perfectly valid aspects of the Muslim legacy, after all.”