Asef Bayat, a professor of sociology and Middle Eastern studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who previously taught at the American University in Cairo, has been studying social movements and revolutions in the Middle East since long before the Arab uprisings began a year ago. The Iranian scholar has written extensively on political sociology, social movements, urban space and politics, contemporary Islam, and the Muslim Middle East. His areas of focus include the Iranian Islamic Revolution, Islamist movements in comparative perspective since the 1970s, and the non-movements of the urban poor, Muslim youth, and women.

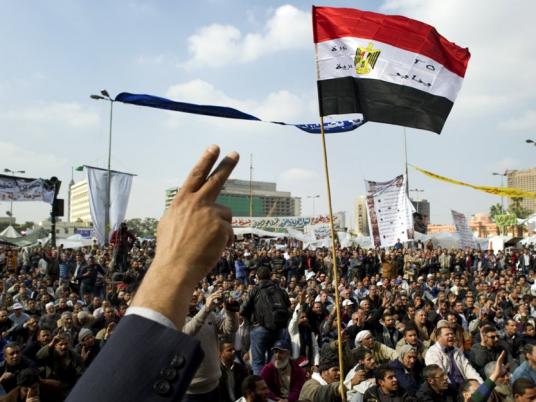

With the one-year anniversary of the start of Egypt’s revolution approaching, many are questioning whether the revolution has succeeded or failed, and how to situate the events of the past year in the context of other revolutions. Egypt Independent recently discussed these issues and more in an extensive online conversation with Bayat.

Egypt Independent: What is your overall evaluation of the Egyptian revolution so far in terms of achieving its goals?

Asef Bayat: The balance sheet of the revolution, so far, is a mixed bag in favor of disappointment for democratic forces. After all, some groups, like the old guard of the Muslim Brotherhood, not to mention the Salafis, are terribly happy with how things are going. But those forces which have fought for and continue to fight for a meaningful democracy, human dignity, and justice, must be disappointed.

Of course all is not gloom. A dictator has been removed. Elections have taken place, even though not to the liking of liberal democratic forces. There is still a good degree of civil society openness. There is still space for good media to operate, and the possibility of popular mobilization in society. The military, after all, is likely to hand over formal power to civilian rule, but is likely to want to maintain a good degree of control over such a government. But the point is that thus far those who made the revolution are not in power. A significant number of the institutions of the old regime — the military, some media outlets, the security apparatus, and such — continue to wield power. These institutions and individuals are acting with an attitude and arrogance as if nothing has changed. This is astonishing!

Egypt Independent: Do you believe that it is time to give up the revolutionary path and focus on the political in order to impose gradual reform? Some people think that revolutionary fervor has waned, and that the general public is tired of continued protests and wants stability.

Bayat: It was of course predictable that revolutionary fervor would wane. Nowhere in the world would ordinary people continue revolutionary, extraordinary struggle for a long time. Egyptians who aim to wage their revolutionary campaign to realize the aims of the revolution probably know this, and so they need to adjust their strategy accordingly. If street politics at this juncture is untenable, then they should seek other avenues.

Egypt Independent: What would determine the fate of this revolution? What would make it succeed or what should be done to make it succeed? On the other hand, what would make it fail? When can or should we say that it has failed?

Bayat: Revolutions are extremely complex processes, because countless factors are involved in shaping them. In Egypt, a minimum requirement to allow revolutionary change to continue — and by this I do not mean continuous street action — is for the military to hand over power to representatives of the people who are democratically and fairly elected. Then you have to wait and see what kind of parliament and then what type of an executive you will get.

Will they be democratic enough to protect the rights of the opposition? Protecting the rights of the opposition — this is the yardstick to measure how much a legislature and an executive are democratic. Otherwise, the country can turn into a ‘majoritarian rule’ where the majority can decide ‘democratically’ to suppress the minority — whether political, religious, or what have you.

In addition, a new democratic government should democratize state institutions: the police, the security apparatus, the bureaucracy, those which are infested by the authoritarian norms of the old and new regime. Finally, it should work hard to realize the social justice component of the revolution — something that most ordinary Egyptians deserve to enjoy. But these cannot be done overnight. It will take a long process to accomplish them. But the point is to make power-holders commit to such a road map. If you have such commitment, you can say that the revolution is continuing, but if not, then one can claim that the revolution is failing.

Egypt Independent: In your evaluation of the status quo, how long will it take for the revolution to achieve its goals?

Bayat: A revolution is not a singular event; it is a multi-faceted process. It is empirically difficult to determine when it starts — just 25 January? — and when it ends. But it does have a breaking point, and that usually is the moment of regime change. But mere regime change is not the end of a revolution; it is rather an essential requirement. Regime change, in theory, allows a revolution to actualize its objectives, depending on what they are. In the case of Egypt, sadly, even that first requirement has not been fully achieved yet. And this makes things complicated.

Egypt Independent: What is the option left to revolutionary forces after the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood as the key civilian political player? Do they need to change their tactics?

Bayat: If we assume that Egypt will operate in a fairly democratic fashion, then it is up to the political forces to make themselves electable. And this needs real work — it needs skill, strategy, resources, organization, and the art of mobilization. However, it is the responsibility of the government to provide equal opportunity for all legitimate parties to be active on the social and political stage and contest for political power. If the Muslim Brotherhood is poised to be a dominant force in both civil and political society, then the revolutionary forces should support and cooperate with those (post-Islamist) factions and elements that extend democratic space. But they should equally criticize and expose relentlessly those who pursue exclusivist, opportunistic, or populist policies and practices. At any rate, one should also bear in mind that religious parties are not destined to win every election. In a democratic environment, things can change. Just remember how in Indonesia just following the downfall of Suharto in 1998, Islamist parties emerged and took center stage. But in later years, especially in 2009, they all lost to secular groups.

Egypt Independent: What lessons or parallels can be taken from other revolutions in history with similar circumstances?

Bayat: One can draw parallels from other historical experiences. I have referred to the so-called color revolutions in some of the ex-Soviet republics like Georgia and Ukraine, where mass street protests forced unpopular rulers to leave office. But the Egyptian experience is also quite particular, especially in terms of its quite remarkable urge to continue the revolutionary struggle. Yet I still think that for the time being the Egyptian experience remains a refo-lution, a mix of revolutionary struggle and a reformist trajectory. It is not a full-fledged revolution, at least not yet.