Consumers may struggle to understand food nutrition panels that include “added sugars,” a study suggests, illustrating the challenge ahead as US health officials consider putting this detail on food labels to nudge Americans to cut back on sweets and empty calories.

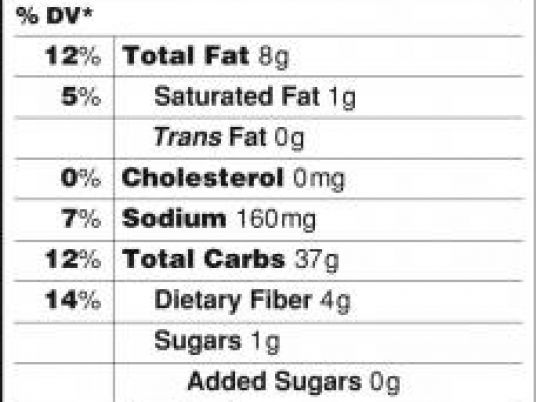

When researchers showed consumers nutrition panels that broke out the grams of “added sugars” as part of the total grams of sugar in the food, many people miscalculated the amount of sugar, the study found.

But when consumers looked at a nutrition panel that didn’t break out “added sugars,” which may more closely resemble what they currently see on grocery store shelves, most of them correctly identified how much sugar was in the food.

“From the consumer perspective, the ability to quickly and accurately synthesize food label information when shopping is paramount,” said study co-author Kris Sollid, director of nutrients communication at the International Food Council in Washington, D.C. “Our research shows significantly greater comprehension occurs when 'added sugars' information is not presented.”

While current food labels must state the amount of sugars, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed overhauling the labels to add an indented line under sugars that breaks out “added sugars” to help consumers understand how much of the sweetener is naturally occurring versus how much is added to the product. Proposed new labels would also make calories and the total number of servings in a package more prominent.

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA), which sets dietary guidelines, considers “added sugars” to be empty calories because they contain no nutrients. Adults eating about 2,200 calories a day should get no more than 265 calories from empty calories like added sugar, according to the USDA.

According to the FDA, the major sources of added sugars in the diet (with the highest sources listed first) are soda, energy and sports drinks, grain-based desserts, sugar-sweetened fruit drinks, dairy-based desserts and candy.

To see how consumers might interpret new labels with “added sugars,” Sollid and colleagues first interviewed 27 adults in Los Angeles, Baltimore and Atlanta. Consumers interpreted the new labels in a variety of ways, including some who thought the “added sugars” were in addition to “sugars” shown in the line above on the label, others who understood that it meant the manufacturer put extra sugar in the product, and some who found products with “added sugars” less desirable.

Then, they surveyed 1,088 men and women to see how they currently used nutrition facts panels and find out if they could accurately interpret “added sugars” displayed in formats that might be adopted in future labels.

Consumers who first viewed the label without any “added sugars” line correctly tallied the total amount of sugar in the food 92 percent of the time. When they saw a label with “added sugars” indented on a line below “sugars,” they were correct 55 percent of the time. And, if they first looked at a label with “added sugars” indented on a line below “total sugars,” 66 percent of them got it right.

Even among consumers who said they frequently read food labels at the store, about 45 percent of them incorrectly identified the amount of sugar when they first looked at the label with separate lines for “sugars” and “added sugars,” the researchers report in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

“There is insufficient evidence that listing 'added sugars' on nutrition facts panels would yield meaningful reductions in calorie consumption or improvement in public health,” Sollid said by email.

But the right design might make a big difference, said Samantha Heller, a nutritionist at New York University's Center for Musculoskeletal Care and Sports Performance who wasn't involved in the study.

“The nutrition facts panel is confusing for just about everyone,” Heller said by email.

Consuming too much added sugar can increase the risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and certain cancers, Heller said.

A better-designed label that made it easy for consumers to understand, for example, that a 16-oz iced tea had 9 teaspoons of added sugar, might lead people to make their own tea or drink water, she said.

“Most people have no idea how much unnecessary sugar they are eating or from whence it comes,” Heller said. “While sugar is a perfectly fine ingredient in many recipes, we are consuming far too much of it and in high amounts in foods that have little or no nutritional value. With the new label consumers will be able to identify the foods that perhaps they should be eating less of.”

At this point, however, the timing of any changes to the labels is unclear. A spokesperson for the FDA told Reuters Health, “FDA is planning to issue a supplemental proposed rule to solicit comment on limited additional provisions and information related to the nutrition facts label. The supplemental proposed rule is currently with the White House Office of Management and Budget for review, and further information will be available after that review is concluded and the document goes on display in the Federal Register.”