Once a year, the winding pathways of the Palace of the Arts are filled with the creative efforts of Egypt’s aspiring generation of artists, the most worthy 300 or so culled from a submission pool of over a thousand. Such a massive output of creative effort is a stimulating and inspiring spectacle to witness, and seeking out those works that truly excite in the halls of the palace, Mahmoud Mukhtar Museum and Al-Bab Gallery can be as thrilling as it is exhausting.

This year’s edition of the Youth Salon — or Salon of Young Artists as it has been renamed in 2011 — includes a large number of installation works, as well as video and a few samples of photography. A number of impressive contributions are, however, among the painting, sculpture and printmaking works that make up the bulk of the exhibition.

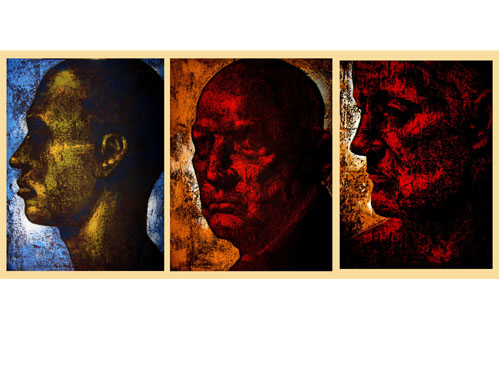

Artists represented in the salon appear to have at last generally rejected the Pharaonic themes that appear in a range of Egyptian modern and contemporary art. Still, there is one work that takes on a slightly less iconic visual tradition of ancient Egypt. Tamer Sayed Ahmed created a collection of portraits taking the Fayoum mummy portraits created in the Late Antiquity as their visual reference. Ahmed’s recreations do not hold the mysterious personality of the original works. He has worked to give them the hazy patina of age to mixed degrees of success. But they are clearly and intentionally images of contemporary young men in modern clothing. While not the most impressive work of painting technically, his figures carry the same quietly mournful gaze of the ancient Fayoum portraits, and the elegiac panels are imbued with an oblique sense of loss that makes one wonder about the fate of these young boys.

Exhibited with the print work and photography was a small piece that stood out for its playful use of paper as two-dimensional sculpture. In nine postcard-sized works, arranged together in a square, Dina Khaled Fahmy cut strips, opened flaps and pinned on ribbons, experimenting with negative space and creating a kind of tiny world of trap doors, tunnels and evocative shapes. Her work is unique for its experimentation with a medium generally considered “traditional.”

Unfortunately, the photographic offerings at the exhibition are primarily inconsequential formal studies, and the medium seems not to have established itself as a vehicle for conceptual work, unless employed as part of a larger multi-media installation. Nor have the young photographers approached their craft with the same attention to technical precision present in printmaking work, for example. How much this unimpressive showing is a result of curatorial choice, however, is up for debate.

Straddling a line between straightforward photography and multimedia installation, Wessam Quresh put together a large, five-part photographic piece exploring the dynamics of public and private space. In a row through the middle of a large square photograph of a chaotic traffic intersection, pasted on the wall, Quresh attached three photographs in ornate gold frames. Two empty domestic spaces, typical Egyptian homes, hang on either side of a drawn portrait of a faceless family, their visages rubbed away. The collection has the marks of personal history, with photographs finished as though they will go on the wall of a family home. Simultaneously, they are generic, with any personal touch or indicator of time carefully removed. The implication and then careful deletion of narrative make for an intriguing presentation.

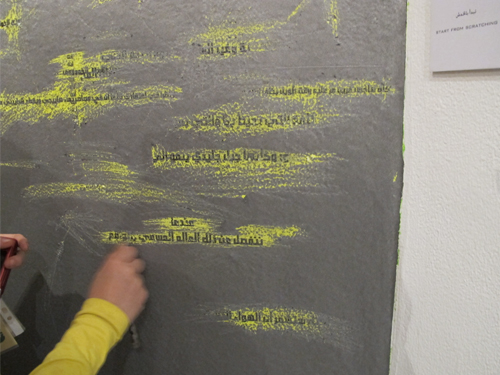

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mai Hamdy’s interactive wall painting was both one of the most crowd-pleasing works, and also the co-winner of the Grand Prize. At first, just gray paint and digital zeros, like a stop-watch out of time (or a timer about to start), the work was painted directly on a wall on the upper level of the Palace of the Arts. Hamdy invited exhibition visitors to take a coin and scratch away the gray surface to reveal a lime green background covered in text.

On the wall beneath, one particularly large statement, already scratched away, jumps out: “I do not think you care what you read here,” Hamdy declares, challenging her viewers to engage with her work. As if proving Hamdy’s point, though visitors all around were busily scratching away, much of the small text remained illegible, most people having grown bored before finishing the job. While immediately attractive for its invitation to participation, Hamdy also poses a challenge to her audience. She plays with her role as an artist and manipulator of the public, promising a state of completion that the work will most likely never reach.

Al-Bab Gallery and the Mahmoud Mukhtar Museum also house selections of paintings, prints and sculptures. The Mukhtar Museum, with few visitors and a generally unimpressive collection of less innovative or technically adept works, feels decidedly like the second-tier selection, raising the question of why they extra spaces are included at all. However, questions about the structure and function of the Youth Salon and the curatorial choices made in its assembly are long-standing, and have been explored in detail elsewhere.

Nearly every prominent Egyptian artist working today has passed through the Youth Salon, and one cannot help but view works wondering which young artist will go on to reach the stature of past participants such as Wael Shawky and Amal Kenawy. Of course we cannot know the future, but amongst an admittedly high number of forgettable works, this year’s Youth Salon has a wide range of exciting new ideas to offer.

The Youth Salon is on view at the Palace of the Arts daily from 10 am to 2 pm and 6 pm to 9 pm.

The Grand Prize, with an award of LE20,000, was given to Osama Abdel Moneim and Mai Hamdy. Salon Prizes, each with an award of LE10,000, were given to Ahmed Qasim for painting, Bassem Abdul Jalil and Mustafa Samir for graphic, Hend al-Falafely for drawing, Ibrahim Saad for installation, Sahar Anani and Hany Gabriel for photography, Ahmad Husseini and Hatem al-Said and Mohamed Kamal for ceramics, Ahmed Bedier and Iman Ibrahim for computer and video work, Ameer Fekry and Majid Michael for sculpture, and Nora Saif and Karim Bassiouny for painting and monoprint.