Over the past 40 years, Xavier Espuna has made his ham and cold cuts business grow from a small venture in Spain's northeastern region of Catalonia into an international business exporting as far away as Japan and Argentina.

Like most Catalans, Espuna is swept up by the movement to split his region off from the rest of Spain. But he is not worried about the consequences that secession from Europe's fourth-largest economy would mean for his business.

The reason – he does not think it will happen any time soon.

"I am focused on making good ham, I am not focused on politics," said the jovial 61-year-old, whose family-owned company is based in Olot, a pro-independence bastion.

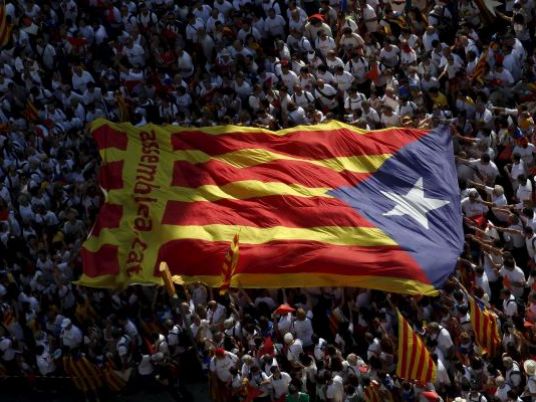

Catalonia, a region that speaks its own language and accounts for about one fifth of Spanish economic output and population, votes on Sunday to elect a new parliament.

Separatist parties running on a joint ticket are expected to win a majority of seats, according to polls. They say they will unilaterally declare independence within 18 months if they win.

Yet the prospect of independence remains a theoretical issue for Catalans, surveys show.

Only 20 percent of Catalan voters actually believe the secessionist campaign will lead to a split, according to an opinion poll in local paper La Vanguardia.

A separate survey from the Center d'Estudis d'Opinio, a body backed by the regional government, showed the issue ranked only fourth in a list of Catalonia's main woes, below unemployment, dissatisfaction with politics and the state of the economy.

"I don't think the elections will have any impact on my business," said Espuna as he walked around his small ham factory dressed in a white butcher's coat.

The apparent ambivalence of the Catalan population about independence before Sunday's vote suggests that, despite the public statements of Catalan politicians, people believe the goal of a separatist drive that began in 2012 is now a more pragmatic effort to win concessions from the central government.

The head of Catalonia's regional government said this week that only secession remained on the table. The Spanish centre-right government of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy has ruled out a Catalan breakaway and opposed any attempt to hold a referendum on secession. It has also dug in its heels on a deeper political and economic dialogue with the region.

But talks on a new and more beneficial tax regime for Catalonia are due to start after a national general election in December. Also on the cards are discussions over increased central government spending on infrastructure projects.

Depending on what party or parties will rule in Madrid after the general vote, there could even be a constitutional change that could include recognition of Catalonia as a nation within the Spanish state.

"People are saying they want things to change in Catalonia but at the same time neither they want independence nor they think it's possible," said Josep Borrell, a former socialist minister and president of the European Parliament.

"They simply want to have a better bargaining hand with the central government."

Boost competitiveness?

The economic consequences of a Catalan secession are the topic of much debate.

Separatists say Catalonia, a rich region that relies on tourism and a network of innovative companies, would become the most competitive economy in Southern Europe if it becomes independent.

They also say its tax revenues, a portion of which is currently transferred to poorer Spanish regions, would increase by 12 billion euros, enabling the new state to provide better social care for its people than now.

The central government says Catalan independence would mean an automatic exit from the euro zone and international trade agreements, followed by capital flight and economic recession.

Foreign Minister Jose Manuel Garcia-Margallo said on Wednesday that close to 700,000 jobs would be destroyed in Catalonia, pushing the unemployment rate to 37 percent.

Special concessions on taxes and infrastructure would unquestionably be a boon for the local economy. A law to better protect regional powers from national interference would also help pave the way for reconciliation.

Talks between Madrid and Catalonia next year depend in part on Catalan politicians' willingness to negotiate. But much will also depend on the makeup of the next central government.

According to polls, at least two parties, probably three, will be needed to form a government in Madrid – possibly setting up the country for a fractious coalition government that would be hard-pressed to negotiate on anything.

"The question is will the state be in a position to table a wide-ranging reform to make Spain attractive again? Frankly, I don't see it," said Lluis Orriols, a political science lecturer at the University Carlos III of Madrid.

Overstated

Some entrepreneurs on the ground are being vocal about their position.

Josep Bou, a proud Catalan who learnt to speak Spanish only when he was four-years-old and owns 13 bakeries across Catalonia, said he is in favor of negotiating better financing terms for Catalonia but is against secession.

He said he did not believe the Catalan economy will be better off in an independent state. He also said divisions between Catalans and the rest of Spain are overstated.

This position has not made him popular among friends – and clients.

"Some clients no longer buy my bread, I have been called a bad Catalan and a traitor. Speaking against the tide is always tricky."

In Olot, Xavier Espuna also said he was not bothered by any divisions. When it comes to his hams and other products, clients abroad think of them as Spanish, not Catalan, and that's fine with him.

"I sell my products all over Spain. Abroad, consumers buy them as typical Spanish products."