Rosetta is not the town it once was, nor does it attract visitors in the same way it once did. It is somewhat surprising, considering that the town is located where the world’s longest river empties into the sea, and where the key to understanding that river’s greatest civilization was found.

Getting to Rashid, its name in Arabic, is somewhat of a hike. Travelers used to make it there by a dahabish boat in the Atfeh Canal or trains, which stopped periodically to pick up goods, making the trip much longer.

Today there is no direct route to the town, but it’s only an hour by microbus from Alexandria, making the trip about five hours from Cairo. Much of the road is barren, but on the approach into the town, palm trees and irrigation canals line the road being used by tuk tuks, and the smell of the burning trash outside the town is replaced by jasmine, which wafts in the sea breeze.

The town’s current incarnation is much more modest than previous ones. The traffic consists mostly of sky blue-trimmed Lada taxis, reminiscent of Alexandria, and horse carts. The mix gives the sleepy town a feel somewhere between the Beheira countryside and Alexandria, the port city that eventually replaced the booming version of Rosetta that rose to prominence exporting coffee during the 17th century.

Rosetta, in its heyday, was the town that kept the Ottoman elite’s pockets — and coffee cups — full. Victorian travelers made their way from Alexandria to see the spectacle of the port and the pulverized mocha beans it sent abroad.

In 1825, one Londoner wrote back to the Morning Post explaining how three men pounded coffee using “enormous pestles, each as large as a man can raise,” as a young boy rhythmically stirred the pounded beans, removing his hand between falls of the pestle in time with song.

These days, Rosetta’s ahwas are instead supplied by roasters in Alexandria. Around the corner from Abaza, the man who runs the ahwa most frequented by locals, 80-year-old Ibrahim Mahmoud Fouda, says he remembers when Mutalib, the last roaster in the area, closed down some 40 years ago.

Abaza is a dimly lit ahwa, but is somewhat unremarkable other than the view it provides of a Ottoman-era merchant home that now operates as a museum. Abdel Moneim Minshawy, 50, has worked there for 25 years, serving Gaber Saad Salam Abu Salaam, 59, all that time.

He says Abu Salaam has sat in the same spot after he finishes work to have shisha and tea. He now only takes half a teaspoon of sugar rather than the four he had in his 20s. The truck driver likes Abaza more than the rival ahwa, Asmar, which lies closer to the Nile, saying it is cleaner and has more to offer.

Other merchant houses line the main fish market, seemingly designed to face away from the common people, with no visible facade and mashrabiyas to prevent unwelcome eyes from peering in. These houses were built by the coffee and rice moguls of the time. Those that aren’t accessible due to renovations can be visited before 4 pm.

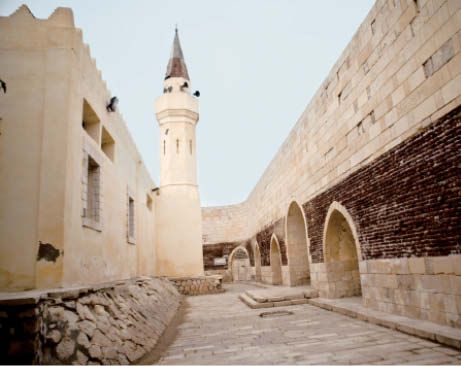

The merchant nature of the city merited some defense of the town and its port, pushing Sultan Qait Bey to build a fortress along the Nile. The sultan’s engineers brought stone from elsewhere to lay foundations for the modest fortress, and in the process they buried the Rosetta Stone under the south tower.

It wasn’t excavated until 1799, when French soldiers that had captured the city looked to reinforce its defenses.

When the fortress was renovated again, this time in 1985 by the Antiquities Ministry, the original brick was covered by smoother stone. Brick factories still line the Nile, the red smokestacks and piles of blocks contrasting with the bright blue and green fishing boats as they shuttle between the sea and the fisheries that supply the fish markets and the fish restaurants along the corniche.

The boats don’t only shuttle fish. Villages near Rosetta are on occasion the staging point for illegal immigration out of Egypt.

Rather than marking the spot where two great bodies of water meet, the Egyptian government has erected another fortress — this time a three-story home to Egyptian border guards with binoculars to watch for movement of ships carrying migrants or contraband.

A few hundred meters inland lies a navy factory for building jetties to prevent erosion, perhaps in preparation for impeding climate change that threatens the town. It’s possible to visit the spot, and photography is prohibited since it’s a military area, although Egyptian soldiers in flip-flops are sometimes eager to pose with visitors.

The border post lies about five kilometers north of the town, on alluvial soil that made its way down the river from the Nile basin. In the time of Herodotus, the town itself is where the river met the sea, testament to how much sands can shift in Rosetta.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.