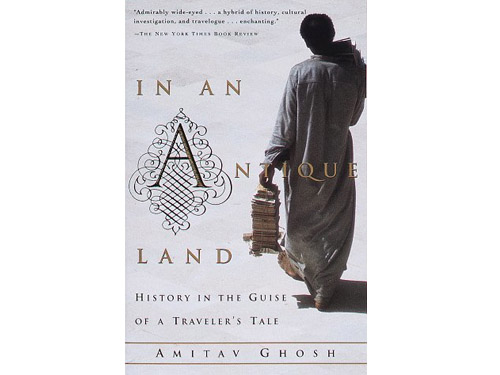

Indian author Amitav Ghosh wrote “In an Antique Land” in 1992. It has two parallel narratives, one about his stay in a village in Egypt’s Delta in the early 1980s, the other on his detective work following 12th-century references to a slave.

In rural Egypt, he tries to learn Arabic and gets to know villagers whose lives are changing as some go off to work in the Gulf and come back with gadgets such as refrigerators.

That main narrative is a self-reflexive frame for the second, which traces trade networks spanning India, North Africa, the Middle East and southern Europe, like an early, more successful version of globalization before the Crusades.

It is based on a pile of papers from 870–1880 found in a synagogue’s storeroom. They were meant to be buried in a cemetery for religious reasons, but no one got around to it. The synagogue still stands in Coptic Cairo, but its receipts and letters, as well as its Quranic, Biblical and rabbinical verses and so on, have long since been wiled away around the world.

It is difficult to believe the papers were written so long ago, especially if the writer quoted is so widely traveled, and his words so ordinary and warm. Ghosh discovers a lot, such as that the Delta dialect is weirdly similar to the North African Arabic his main medieval source spoke, that colloquial Arabic could be written in Hebrew characters and strewn with Aramaic, and that conceptions of slavery were completely different.

Ghosh is full of wonderment and humility. His open-ended genre illuminates the personal reasons behind his anthropological work. Most wonderfully, his own experience and his description of an ancient multi-faith, multilingual world offer hope about different people being able to live together.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.