The days are largely gone when photographers got their hands dirty soaking paper and film in slippery chemicals. But the medium remains difficult to grasp – ubiquitous yet amorphous.

Photography is a visual language used to express everything from war to fashion, conceptual art to family memories. As technology continues to make it more portable and accessible, photography has woven itself into being an integral part of our lives.

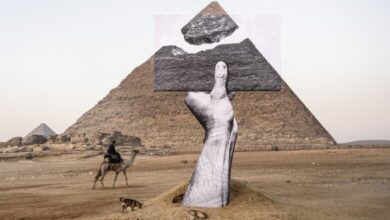

With the internet heavy with images of all kinds, the task of artists who use photography to distinguish their work from the vast sea of images has become even more difficult than before. Some artists in Egypt – and elsewhere – are leaving behind this task and embracing photographs as the visual language of life.

Still fighting for recognition

Photography may have spent the first half of the twentieth century fighting to be recognized as a fine art in the Western canon, but by the latter half of the century the medium held a firm place in contemporary art, with practitioners such as Cindy Sherman becoming part of the contemporary art establishment.

In Egypt, the art establishment has yet to formally recognize photography as an art form. The draconian categories of the Syndicate for Plastic Arts exclude photography, along with any kind of new media or performance art. Hence, artists working in one (or several, as many artists do) of these media find it difficult to become members. However one feels about becoming a government-ordained artist, this institutional lack of recognition extends to art education as well, in which photography education is marginal.

Photographers working in Egypt often sense a lack of respect for the craft and the profession. Russian photographer Xenia Nikolskaya teaches photography at The American University in Cairo and is completing a book, documenting abandoned places in Egypt. She found that bringing a cinema producer along on her shoots made people more welcoming to her camera.

“When he presented himself as a film production manager, I was able to access the abandoned places. Cinema is a respected medium versus photography, which is generally connected with journalism,” she said.

Karim Mansour, an independent artist and documentary photographer, echoes Nikolskaya’s sentiments. “A photographer is not considered a well-respected job, and this is evident in the language people use – ‘mosawarati’.” This colloquial Arabic word for a photographer suggests a lack of gravity.

Obstacles to production

It is almost impossible to create exhibition quality prints or to use larger format films in Egypt due to lack of facilities.

Rana ElNemr, an artist and photographer in Cairo, explains that to print in Egypt, artists must seek out individuals who work in developing or printing facilities and are willing to spend extra time creating quality prints. “Everyone has a few names and numbers of people who can make good prints,” says ElNemr.

Bas Princen’s “Refuge: Five Cities’ Portfolios” exhibition, shown at the Townhouse Gallery last month, exemplifies the kind of work that is both typical of certain strains in global contemporary art photography and cannot be made in Egypt. The Dutch photographer’s prints are large, digital prints made from scanned negatives, produced through a laborious process of collaboration between the artist and a printing specialist.

The Contemporary Image Collective (CIC), founded in 2004 by a group of Egyptian artists and photographers (including ElNemr) has, as its express purpose, the support of the photographic image in all its myriad forms, artistic and otherwise. It holds regular exhibitions and workshops that are oriented toward both technical education and the creation of a critical dialogue about photography.

“When students really start to think of themselves as practitioners, they then also begin to be a potential audience,” says CIC Artistic Director Mia Jankowicz.

The unclassifiable image

Grand-scale work common in Western contemporary photography, like that of Princen or photographers like Jeff Wall and Philip DiCorcia, is in short supply among Egyptian artists, as the structures that support such work are absent in Egypt. Hence, the image takes on a more amorphous role.

Hala Elkoussy has worked with photography for much of her career, but in more recent work has moved toward installation and collage. Her 2010 “The Myths & Legends Room” is a 9-by-3 meter photo-collage mural that constructs a narrative of Egyptian history, a wild scene that tells a story from the perspective of human moments, personal experience and jumbled symbols.

“The Myths & Legends Room” is exemplary of a mode of working with photographs that is more interested in appropriation and re-contextualization than creation. This can also be seen in the way the vast volume of images created by the events of the 25 January revolution are already reappearing as part of new artworks.

Indeed, the city of Cairo and, more generally, life in Egypt play an important role in the work of many photographers. At its most basic, a photograph is a document, and ElNemr and Nabil Boutros are among a number of artists who, while maintaining value for photographs as aesthetic objects with conceptual properties, use images as tools to organize and classify phenomena.

Rana ElNemr creates work that documents elements of the visual landscape of Cairo, working on long-term, exhaustive projects like “The Balcony Series”, in which she photographs idiosyncratically decorated balconies.

“I collect and organize information to make sense of my surroundings,” says ElNemr. Her work becomes, in a way, a catalogue of specific visual elements of Cairo.

Similarly, Nabil Boutros created a taxonomy of Egyptian men in “Egyptians”, and his series, “Egypt is a Modern Country!” is comprised of diptychs and triptychs that document the development of suburbs and provincial cities in Egypt. The series gathers images of change taking place in Egypt, but relies on juxtaposition to frame the issues at play, creating a fractured conversation in each piece.

The use of images as part of a dialogue is employed in a different way by Iman Issa, whose “Triptychs” combine text, postcard-sized snapshots, photographed still life installations, as well as text and physical objects. She uses photographs as documentary and aesthetic objects in the case of the photographed still lifes, but also as a trigger for memory with the small snapshots. The result is a quiet conversation that comments both on political and social conditions in Egypt as well as the function of images in her individual thoughts and memories. Issa’s “Triptychs” takes images and objects out of their everyday contexts and re-contextualizes them, this time amid objects of the everyday, carefully constructed into a narrative.

Photographs are more a part of our lives than ever before, making it important to look at the function of images in our collective and individual existences. It is difficult to isolate images, elevate them and ask the public to approach them as objects that go beyond documentation, but some Egyptian artists are embracing the photography flood and making work that draws from and analyzes the visual tableaux of society.