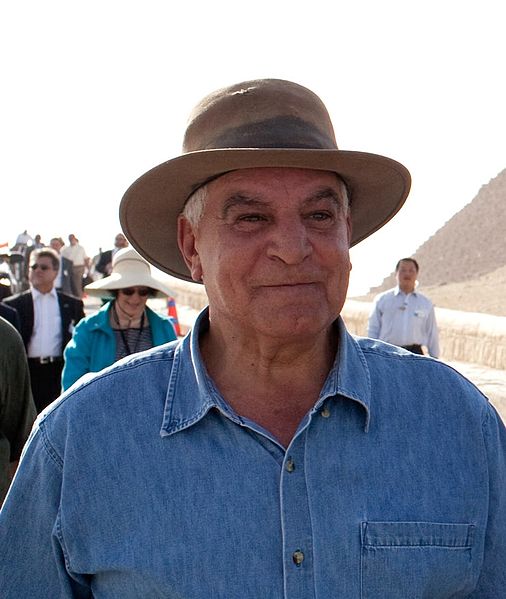

Zahi Hawass has never exactly been afraid of making enemies. Egypt’s 63-year-old antiquities chief (a man who cheerfully refers to himself as “The Pharoah”) has, over the years conducted public feuds with fellow Egyptologists, prominent international museums and a host of alternative archeologists who he cheerfully dismisses as “pyramidiots.”

Hawass’ latest target isn’t exactly new; for years he has railed against foreign museums holding onto treasured Egyptian artifacts that he believes should be returned home. At the top of this list is the Rosetta Stone, currently housed in the British Museum in London.

“I believe that unique artifacts and masterpieces should not be away from their mother countries,” Hawass said in an interview with Al-Masry Al-Youm. “Even if some of the artifacts left legally, still I want them back!”

Some of the institutions targeted by Hawass have argued that they can better preserve and protect the priceless antiquities that home countries like Egypt could–an attitude that the foreign archeologist calls, “a slightly dubious colonialist excuse." But recent events may serve to add ammunition to that argument; as more details emerge about the apparently nonexistent security measures that allowed a $50 million Van Gogh painting to be stolen in broad daylight from a local museum last week, it's hard not to wonder whether the Rosetta Stone might just be better off in London.

Now Hawas is expanding his campaign and raising the stakes–recruiting other like-minded countries and seeking to turn up the international pressure. In April of this year, Hawass hosted a conference bringing together representatives of two dozen countries around a common cause: jointly seeking repatriation of national treasures, most of which were removed by European powers during the colonialist era.

The conference ended with the formulation of a joint wish-list of items each country wanted back. Beyond the Rosetta Stone, Egypt’s wish list includes a bust of Nefertiti in Berlin’s Neuesmuseum and a statue of Ramses II on display in a museum in Turin, Italy. Several other countries, including Libya, Greece and Nigeria submitted their own lists, with many of the most desired items being held in either the British Museum or the Louvre in Paris.

Hawass said he plans to make the conference an annual event, and steadily increase the public pressure on countries and institutions. “It is a very big deal. It’s not just Egypt, other countries are getting together which is something that hasn’t happened before,” said Salima Ikram, an American University in Cairo Egyptologist who has worked with Hawass for years. “There are no precedents for most of this. The precedents are pretty much being made now.”

But Ikram also admits she understands why institutions like the British Museum are unlikely to ever give in to Hawass’ demands. “If one object is given back to Egypt, then maybe Benin will want something and all the museums of the world will empty out,” she said.

It remains to be seen whether Hawass’ campaign will succeed, but if he fails it certainly won’t be for a lack of trying.

In addition to the museum campaign, Hawass’ staffers closely track the world’s auction houses with an eye on stolen antiquities. In one case—a particularly bitter dispute with the St. Louis Art Museum in Missouri–Hawass has tried to rally armies of children through his online fanclub to boycott the museum and write angry letters to the administration. “I’m going to fight. I’m going to go and tell the world that these countries have no right to these antiquities,” he said. “I don’t understand how they can claim to educate children with stolen goods.”

He boasts that he has personally secured the return of more than 5,000 artifacts to Egyptian soil. Just last week the Canadian government announced it would return a small marble bust seized by customs officials in 2007. And last year, Hawass won a very public battle of wills with no less an institution than the Louvre over five ancient wall frescoes. The French agreed to return the paintings last fall after Hawass played his ultimate trump card: cutting off ties and banning that institution from working in Egypt.

“When (the Louvre team) applied to work in Saqqara, I refused,” Hawass recalls proudly. “These museums have an interest in working here. But we don’t have to work with them.”

Of course that kind of tactic can easily spiral into a diplomatic incident if Hawass does it haphazardly, and it only works if he has the full backing of his own government at the highest levels. Fortunately for Hawass, that seems to be the case; Last fall, President Hosni Mubarak appointed him a vice-minister of culture, meaning Hawass no longer faced mandatory civil servant retirement this year and could serve indefinitely.

Hawass has more than his share of critics, who regard him as more showman than scientist—a media-hungry tyrant who cares more about good television than good science. It’s telling that very few archeologists with any ambitions to continue working in Egypt are willing to speak on the record about him. “I think Egyptologists kind of laugh and shrug their shoulders at Zahi,” said one foreign archeologist who has worked extensively with Hawass and requested anonymity so as not to jeoperdize their relationship. “There is a lot of bluster involved, but I think a character like him is sort of needed.”

For those critics, Hawass often makes it too easy; his current History Channel reality show “Chasing Mummies,” often verges on self-parody. Hawass is depicted as a sort of barrel-chested Indiana Jones, personally risking his safety as he rappels into unexplored caves and dig-sites. In a rather obvious bit of staged drama, Hawass rushes to rescue a naïve young foreign assistant who somehow managed to get herself locked inside a Saqaara tomb. The show also depicts Zahi at his most boastful and imperious. He is shown berating underlings in both English and Arabic, talking about himself in the third person and generally acting like a bit of a cartoon. Perhaps the most amazing thing about the Zahi Hawass reality show is that it took so long for someone to think of it.

“On so many levels, he’s just ludicrous. He’s beyond even self-parody. And yet the job he does is so important,” said Dan Lines, a former Egyptologist and one of the founders of Egyptastic, a website largely dedicated to lampooning Hawass. Among the top stories currently on the Egyptastic site: “Hawass to play ‘bullying tantrum-prone buffoon’ in new comedy show.”

Lines no longer works in archeology, which makes him unafraid to speak on-the-record about Hawass without fear of being blackballed from Egypt. But despite calling him, “a completely out of control buffoon,” even Lines can’t help admitting some grudging admiration for Hawass. Lines, who worked in Egypt on archeological digs for several years, recalls Hawass’ influence on the Supreme Council for Antiquities, when he took over in 2002.

“There was a sense of an organization being whipped into shape,” he said. “The SCA has become more professional on his watch.”