For a lot of people around the world, the word "clown" conjures a specific mental image – one that involves face-paint, brightly colored wigs and oversized shoes. Egyptian kids, however, would be quick to point out how absurd that is, since clowns don’t even have feet.

While different cultures have different ideas of what makes a "clown," the idea of a human clown has never really caught on in Egypt – probably because there’s something inherently upsetting about watching an adult in face-paint act like an infant. Instead, the traditional Egyptian clown, known as the "aragouz," is a combination of wood, plastic and cloth, only brought to life by a skillful (or not) puppeteer who has a piece of metal lodged in his throat.

Instantly recognizable due to its pointy hat, pencil-thin moustache, and, most importantly, an almost incoherent helium voice, the aragouz has long been a staple of Egyptian folklore, with records of its popularity dating several centuries back. Typically, the aragouz is presented as a not-too-bright everyman, who finds himself in all sorts of bizarre situations which he will resolve by using childlike logic, or, failing that, hitting people with a big wooden stick. Occasionally, these slapstick charades will involve a cast of supporting characters such as the aragouz’s wife, a law enforcer, a black person with a funny (read racist) accent, and a villain of some sort – usually arriving in the form of a corrupt ruler, or politician.

In recent decades, however, and with the introduction of satellite television, the internet and videogames, the aragouz has suffered a gradual decline in popularity. Whereas in the 1980s and '90s, its presence was ubiquitous in any child’s birthday party, today the aragouz has to be sought out and hunted down, usually found in venues specializing in more folkloric aspects of cultural entertainment. And while it may be a bit premature to announce the death of the aragouz, it’s not by much. According to performer Saber al-Masry, “the aragouz isn’t dead yet, but it will be in a couple of months, when I’m dead.”

Saber’s statement isn’t one of arrogance, just tragic reality. Having been performing for over half a century, Saber – born Mostafa Osman – has become, for all intents of purpose, the “father of aragouz performers in Egypt,” according to his peers. With his shrunken right arm, missing eye, and a wide scar running down the length of his face, the octogenarian seems an unlikely candidate for one of the country’s leading children’s entertainers, but, as he puts it, “nobody ever sees me. I’m just a hand and a voice,” he smiles, pulling out the little metal throat piece from his pocket and rolling it around in the palm of his hand.

This handmade device, called an “amana,” is responsible for an aragouz’s most distinctive feature. Performers will carefully lodge it at the top of their throat, against the roof of the mouth, using it to elevate the pitch of their voice. As implied by its name, which translates equally to “fidelity”, “honesty” and “safekeeping,” the amana is a source of personal pride and significance to each performer, usually handed down to them by fathers who were also aragouz artists. Saber, however, made his own, shortly after being entranced by iconic entertainer Mahmoud Shokoko’s legendary aragouz performances, many of which were given at a venue in Saber’s neighborhood. “It was at an outdoor nightclub,” Saber says. “I can’t remember what it was called, but it’s the Khaled Ibn al-Walid mosque now.”

“Back then, the aragouz wasn’t specifically children’s entertainment,” Saber recalls. “In fact, aragouz acts were common in adult-themed nightclubs, and their material was typically quite risqué.”

After being introduced to the art by Shokoko, whom Saber developed a relationship with, the 20-year-old turned his attention to the mawalid – raucous local festivals, usually marking a religious holiday. Saber would wander the festivals, spending time with performers and learning as much as he could.

“The sound of the aragouz’s voice, the way it moved and the laughter it evoked; that was what attracted me to the art in the first place,” Saber explains. “And I was able to study that and learn as much as I needed to from the performers at these festivities.”

“They were masters of what we call the ‘baladi’ show,” he says. “Simple humor arising from simple situations. It’s not high drama, but the people loved it, children and adults. And I became very good at it, as well.”

In the 1970s, Saber and his performing partner – a wooden puppet which Saber carved and painted himself, in order to “follow tradition and also save money,” – made the transition to Mohamed Ali Street, a location notorious for its clubs, bars, and decadent nightlife. “I started performing alongside Shokoko, and, when he noticed how good I was, he began to arrange gigs for me – children’s birthdays, adult parties, and such,” Saber says with a clear fondness for what he considers the golden age of aragouz artistry.

Today, things are different for Saber. As a regular performer in Khan al-Khalili’s Beit al-Suheimi, Saber has long abandoned his “risqué” routines, instead using his act to impart moral lessons and advice for children. “I’ll teach them things like the importance of brushing their teeth, and not sticking their fingers in electric sockets,” he says.

“The aragouz is, and always will be, a symbol of Egypt,” Saber insists. “Why else would it be called the ‘people’s puppet’?” However, he is still willing to admit – begrudgingly – that “today’s performers don’t seem to have that certain ‘magic’. Their acts aren’t as developed as ours used to be, and neither are their skills.”

“Performing with an aragouz requires a very specific type of talent,” says Saber. “Either you have it or you don’t.”

Chico the Magician agrees. “Just recently, I was playing the tabla in a band supporting a young aragouz performer,” Chico says. “He was terrible. We kept having to play quieter and quieter because his voice was so weak.”

Unlike Saber, Chico, aka Sabry Saad Metwali, inherited his amana from his father, who was also an aragouz performer. “As a child, I was more interested in magic and acrobatics than aragouz acts, but when my father died, I felt like I had to take his place. And also, I had become too fat for acrobatics,” Chico admits. “It was a tough transition. The first few times I tried to use the amana, I gagged on it.”

Over the years, though, Chico improved enough to become, after Saber whom he trained under, the most recognizable name in the admittedly small world of aragouz performers. He does not, however, share his mentor’s pessimism. “I think I’ll be around for a little longer than a couple of months,” the 58-year-old laughs, his eyes twinkling behind a pair of cracked and slanted prescription glasses.

“The younger performers aren’t terrible,” Chico states. “They’re just underdeveloped, like Hajj Saber said. They need time, and practice – we did too,” he adds, turning to Saber, who grunts.

In fact, Saber remains in a sour mood for the duration of the meeting, cheering up only when asked to describe his favorite routine. “It’s about land theft,” he says, his eye lighting up. “A foreign man steals the aragouz’s land, and when the aragouz tries to get it back, the man kills his son. A lot of people get involved and it turns into a huge deal, and it ends when the aragouz steals the foreigner’s gun, and kills him with it.” Saber then asks for this reporter’s opinion and, upon hearing the response – “it’s really, really violent” – throws his head back in laughter. “I know!” he cackles.

An unusual man with an unusual talent, Saber can never be criticized for not being passionate about what he does. Both he and Chico have a strong love and fascination for their professions that is immediately evident – “I also dance and make masks and play instruments and anything else,” Chico gushes while shaking this reporter’s hand. Sadly, this does little to change the fact that an art that has survived for centuries might not live much longer beyond these two pioneers. Despite his cynicism, Saber remains hopeful.

“I don’t know what will happen to this artform, but I pray that it will live on,” the old man sighs. “Far too many things just fade away.”

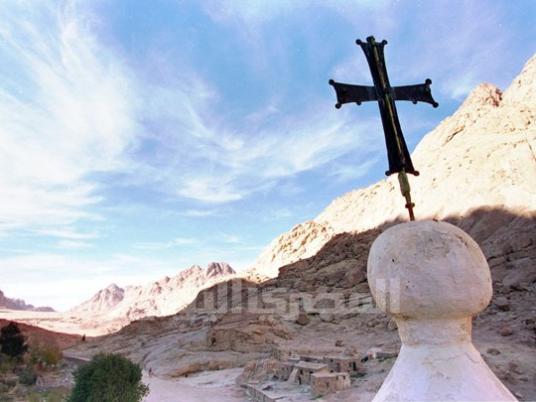

Saber and Chico perform every Friday at Beit al-Suheimi, immediately after Maghreb prayers. During Ramadan, their shows start at 9:30 pm.

Beit al-Suheimi, Darb Al-Assfar alley, off Mo'ez Street, Gamaliya