Sixty years after the 1952 revolution, the legacy of both President Gamal Abdel Nasser and his regime remain fraught territory. Was Abdel Nasser a true friend of the poor? Was he an enemy of Islam? How should he be remembered? Abdel Nasser has been the subject of a number of literary depictions over the last half-century, from laudatory to humorous to critical.

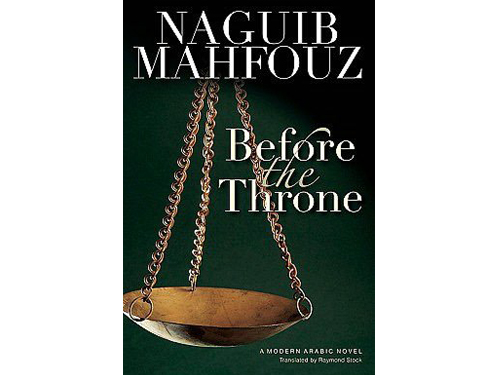

Naguib Mahfouz's 'Fear' and 'Before the Throne'

Mahfouz’s short story “Fear” is about a society controlled by various gangsters. That is, until a powerful army officer comes onto the scene, defeats the gangsters, and becomes the sole power. Mahfouz told writer Mohamed Salmawy, "More than once, I was stopped by [Egyptian] officers in the street. And they would question me straight away about what I meant by the story and who was the real life character of the despotic officer in the story." Mahfouz did, however, find ways of not answering that question, including in his later interview with Salmawy.

Egypt’s Nobel Prize-winning author had a complex relationship with Abdel Nasser; he was both censored and feted by his regime. The Egyptian president very nearly censored Mahfouz's “Adrift on the Nile,” but was reportedly talked out of it by the culture minister of the time.

In one of Mahfouz’s post-Nasser works, the 1983 “Before the Throne” translated by Raymond Stock in 2009, the rulers of Egypt are each called to explain themselves, from Egypt’s earliest days through Anwar Sadat. "True democracy to me," swears Abdel Nasser, "meant the liberation of the Egyptians from colonialism, exploitation, and poverty." But, while Ramses II is portrayed as a big fan of Abdel Nasser, this opinion is not shared by all. Menes, for example, announces, "Your interest in Arab unity was higher than your interest in Egypt's integrity[.]"

Also in the book, one-time Egyptian prime minister Mustafa al-Nahhas rails against the Nasser regime, although allowing that Abdel Nasser “kept faith with the poor." "You were heedless of liberty and human rights," Nahhas resumes his attack. "While I don't deny that you kept faith with the poor, you were a curse upon political writers and intellectuals, who are the vanguard of the nation's children. You cracked down on them with arrest and imprisonment, with hanging and killing, until you had degraded their dignity and humiliated their humanity…. See how education was vitiated, how the public sector grew depraved! … And what was the result? Clamor and cacophony, and an empty mythology — all heaped on a pile of rubble."

Waguih Ghali's 'Beer in the Snooker Club'

Ghali's 1964 novel is a painfully brilliant examination of the years that followed Egypt's 1952 overthrow of colonial rule, and how the narrator — Ram — and his friends find it impossible to participate in anything akin to building a new Egypt. Moreover, they find that little has changed in class structure, and their social club remains largely untouched, except for the addition of a few army officers. The Abdel Nasser described here is neither a friend of intellectuals nor a friend of the poor.

About Ram's friend Font, who has just been railing about Hugh Gaitskill's betrayal of the anti-nuclear movement, Ghali writes:

“Admittedly he began by being furious about Egyptian internal politics as well, but that too was ludicrous, like a Lucky Jim would have been in England during Dickens’s time. It was like trying to ice a cake while it was still in the oven. Font knows how to trim a cake, and frost it, and garnish it with the latest decorations, but he doesn’t know how to bake the cake. So he has to wait for Nasser to bake it for him before he can add his own refinements — and he’s not too sure that he will be allowed to do that, even later on.”

Sonallah Ibrahim's 'Zaat'

We are told early in the novel — published in Arabic in 1992 and translated by Anthony Calderbank in 2004 — that, "Kind generous Zaat was a loyal daughter of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s revolution[.]"

And then, in this very funny passage, which speaks for itself:

“The nocturnal visits that Zaat received increased. They had at first been confined to her father and Gamal Abdel Nasser, but they had now been joined by Manal's husband after he got his PhD…. These visits were characterized by a considerable amount of sweet tenderness until some violence started to creep in. Gamal Abdel Nasser would regularly turn away from her all of a sudden and charge into the kitchen, pick up a hammer, and lay into the walls and cupboards, then move onto the bathroom. Zaat would wake up terrified, shouting: ‘The kitchen…the bathroom…’ Abdel Maguid would rush off to get her a glass of water, annoyed that Gamal Abdel Nasser was coming round to his flat, providing with his attitude toward the walls one more addition to a record laden with crimes of aggression against the rights and property of others. When he came back with the glass, some hope had returned, and he asked his wife: ‘Are you sure it was Abdel Nasser and not El Sadat?’”

Gamal el-Ghitani's 'Zayni Barakat'

"Zayni Barakat is not Nasser," Ghitani has told Al-Ahram Weekly. And yet, to readers — including Edward Said, in his introduction to the English-language edition of the book — it has always appeared so.

In Said's foreword, he insists that: “El-Ghitani's disenchanted reflections upon the past directly associate Zayni's rule with the murky atmosphere of intrigue, conspiracy and multiple schemes that characterized Abdel Nasser's rule during the 1960s, a time, according to Ghitani, spent on futile efforts to control and improve the moral standard of Egyptian life, even as Israel (the Ottomans) prepared for invasion and regional dominance.”

Mohamed Mansi Qandeel's 'Moon Over Samarqand'

The Gamal Abdel Nasser of the 2004 “Moon Over Samarqand” (2004), translated by Jennifer Peterson in 2009, is dark-skinned and charismatic, but he is most particularly the leader who assassinated Muslim Brotherhood leader Sayyed Qutb.

Character Nurallah tells the novel’s narrator of how he had to board a plane as a delegation of Soviet Muslims to show his support for Abdel Nasser "for what he was doing to the Muslims in his country. An ironic paradox. … But I boarded a plane amid a delegation of dummies, and went with them to congratulate Abdel Nasser because he had deigned to arrest Sheikh Qutb."

When Nurallah speaks with Qutb in Cairo, he asks about Abdel Nasser, "Is he really such a false god?" Qutb tells him that he once believed in the free officers "more than I should have." Qutb had defended their mistakes, but he "could not defend them as they turned away from Islam."

Later, about Nurallah’s meeting with Abdel Nasser, Qandeel writes:

"Several doors were opened before them and the corridors of the palace became a royal maze. They were slowly approaching Abdel Nasser. He stood before them, shaking their hands one after the other, and the cameras were struck with a mad fever. His face was darker than it appeared in photographs, but his piercing eyes lit his face and granted it a captivating magic. His large nose, however, revealed his all-engulfing tendency toward control."

Nurallah tells Abdel Nasser that Sayyed Qutb "is frail," but Abdel Nasser silences him.