The Pentagon is poised to release a much-anticipated report on shutting down Guantanamo Bay, even as Congress battles to block the transfer of the military prison inmates from Cuba to US soil.

Officials have said the report on US prison sites that could house the last Guantanamo detainees — enabling President Barack Obama to fulfil a key election pledge — would be published in the coming days.

Its findings are sure to fuel debate on the fate of dozens of longtime captives from America's "War on Terror" who may well spend the rest of their lives behind bars.

Obama has been pushing since taking office in 2009 for the closure of the facility on a US Naval base in Cuba, but lawmakers have repeatedly thwarted him.

On Tuesday, Congress extended a ban on the transfer of detainees to the United States. The ban was inserted into a defense spending bill. Obama indicated he won't veto the bill, as he has with previous versions, raising the prospect he may issue an executive order to get the job done.

Currently, 112 inmates remain at Guantanamo Bay, which has housed about 780 detainees since the start of 2002.

The Pentagon this year sent a team of experts to review US sites that could house dozens of the most dangerous detainees following the closure of the prison.

US sites considered include the Consolidated Naval Brig in Charleston, South Carolina; Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, and a federal prison complex in Colorado that is already home to Egypt's Ramzi Yousef, who bombed the World Trade Center in 1993, and "Unabomber" serial murderer Ted Kaczynski.

The Colorado prison comprises medium, maximum and supermax facilities. The Pentagon also considered a state prison in Colorado's Canon City.

Political fears

Lawmakers from areas that could host the so-called "Guantanamo North" are incensed.

"I will not sit idly by while the president uses political promises as a means to imperil the people of Colorado," Republican Senator Cory Gardner of Colorado wrote on Facebook.

"Despite the president's campaign promise to close the prison facility at Guantanamo Bay, the American people continue to roundly oppose such a plan."

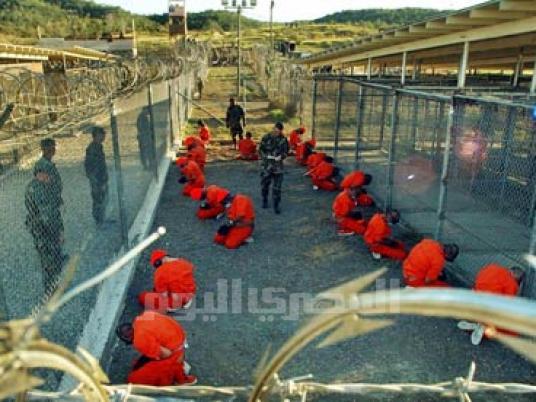

The United States opened Guantanamo to hold terror suspects following the September 11, 2001 attacks, and photos of shackled men in orange jumpsuits became a defining image of US foreign policy in the early 2000s.

Inmates were called "enemy combatants" and denied standard US legal rights, meaning many were held for years without charge or trial.

The Guantanamo population has dwindled, and prisoners no longer deemed a risk have either been repatriated or sent to a host country.

Of the remaining 112 inmates, 53 have been cleared for transfer to other countries, though Defense Secretary Ashton Carter must give final approval for their release.

But most of them are Yemeni, and their country is in a state of civil war — so they cannot go home.

Obama "really botched it by waiting so long to transfer detainees," David Remes, a US lawyer who represents some of the detainees, told AFP.

"For a couple of years he did not transfer Yemenis back to Yemen, and now he cannot."

Meanwhile the administration has been openly making plans to transfer the 59 most dangerous inmates to the United States.

Carter acknowledged in September that many of the remaining inmates may never be released, for security reasons.

"Some of the people who are there at Guantanamo Bay have to be detained indefinitely, they've just got to be locked up," Carter said. "Half of them… are not safe to release, period."

Rights groups are furious America could hold prisoners without trial for the rest of their lives.

"Every day individuals remain indefinitely detained is another day that the United States commits human rights violations and loses its credibility to press for protection of human rights around the world," Amnesty International said.