There are at least three things to consider when looking at the current crisis unfolding in Egypt.

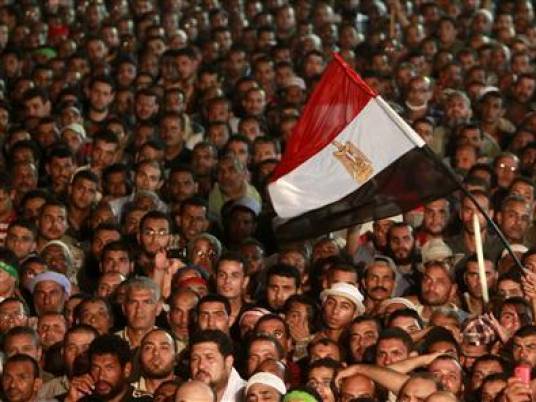

Contrary to the navel-gazing some political analysts and activists are still finding time to indulge in, the thing most Egyptians worry about now is national security. They took to the streets on 26 July to reiterate their rejection of the Muslim Brotherhood, its political failures and attempts at hegemony over state institutions and the economy. That day army chief General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi also asked for a mandate to confront "violence and terrorism." Finaly, it was a message to the international community from both Sisi and the people to refute claims that 30 June was a military coup.

Violence and terrorism certainly need to be tackled. No country can rebuild itself with the threat of terrorism on its borders, inside its cities. The Muslim Brotherhood's decision to militarise its fight to return Mohamed Morsy to power has delegitimised the organization as well as its message. It has left no room for dialogue because no nation on earth would agree to negotiate with terrorists and armed militias.

The Brotherhood has to make the decision to put an end to violence, whether in the Sinai (through their affiliates and supporters who are waging a daily war on military targets and personnel), or in the cities of Egypt (and put an end to bombing public areas like Mansoura, initiating violence against civilians and military targets, and attacking innocent people on the streets). Only then can there be any hope of a national reconciliation and a possible rehabilitation of the Brotherhood back into the fold of Egyptian society.

The second concern is the social aspect of this war against terrorism. Any hopes of national healing are gone for the short term. The 25 January revolution failed to create any coherent consensus, due to a lack of political will and the absence of strong leadership.

The scene was already set for the Brotherhood to further inflame social divisions, causing religious tensions, social strife and a general disintegration into lawlessness. For the first time in recent history, Egyptians felt it was alright to take matters into their own hands and make sure “justice” was served. In the absence of a strong security presence, many incidents took place across Egyptian governorates were people decided to punish individuals or religious groups for crimes real or imagined, causing chaos and bloodshed.

This spirit has not miraculously lifted after 30 June and the ousting of the Brotherhood from power. We have witnessed a return of sectarian violence in Minya, which was condemned by only a few so-called liberals and politicians, both at home and abroad. There have also been some sporadic outbreaks of social violence carried out by citizens against members of the Brotherhood in their neighbourhoods, such as the recent reports of torching Ikhwan-owned shops in Port Said. There is a fine line between tackling terrorists and demonising the other, and this line should never be crossed. It is a dangerous and slippery slope that could lead to exclusion, oppression and a vicious circle of civil strife.

On the political front, the situation is not any better. The same political ineptitude, prevarication and lack of leadership that plagued the scene after January 2011 is still present. Many analysts and activists are still arguing over whether 30 June was a revolution or a coup; should people have taken to the streets on 26 July in support of the army; is this a “militarisation of the Egyptian collective psyche,” etc.

While all these questions are important for analysts, writers and historians to deliberate over in years to come, now is the time for political action and strong leadership. Instead of wasting time pondering whether the military, and General Sisi, are planning to take over ruling the country, all so-called “democratic,” “liberal" and non-Islamist political elements need to focus their efforts on making sure that scenario doesn’t actually happen. If they do not want the country to fall into military rule, they should provide a strong civil alternative. They should start working on the ground, gaining grassroots support, and developing a vision for the nation to move forward. What they should worry about right now is that in the absence of strong political leadership and vision, the army could very well find itself left with no option but to be the de facto ruler of the country. General Sisi has proven, throughout last year and since Morsy was installed as president, that he is perfectly willing and capable of working with any civilian government that is in power. In spite of the conspiracy theories trying to prove otherwise, the main reason the army literally had no option but to intervene on 3 July was the complete absence of other strong state institutions.

After decades of dictatorship, and a year of Ikhwan rule, Egypt almost became a failed state, with fragile institutions and a complete lack of potential civilian leadership. If political actors continue theorising and don’t start acting now, the army again will find itself in the unenviable position of having to take over to save Egypt from complete and utter failure.

Dina Hamdy is an Egyptian political analyst currently based in London. Formerly worked as a journalist in Saudi Arabia and as Senior political analyst in the British Embassy in Cairo.