This month, Aswan’s famous High Dam celebrated its golden anniversary, marking fifty years since its construction and the resultant migration of the Nubian peoples that had previously lived in the area. In an exclusive interview with Al-Masry Al-Youm, Sharaf Abdel Karim, head of the Nubian Heritage Association, takes a sentimental journey back to Egypt’s lost "Land of Gold."

Al-Masry Al-Youm: How do you feel today, 50 years after the building of the Aswan High Dam?

Sharaf Abdel Karim: Construction of the high dam was an enormous national project that every Egyptian contributed to. Nubians in particular sacrificed their possessions, including 45 Nubian villages lying on 300 square kilometers of land and one million palm trees. We were moved from a paradise on the banks of the Nile. These treasures are all submerged under water now. Along with the loss of the land, there was also the loss of our heritage, values, memories and lifestyle, and, above all, our proximity to the water, the primary source of life.

Al-Masry: Was the transition smooth? How long did it take?

Abdel Karim: Six month to move 45 villages. The last one was moved on 18 October, 1964. The transition was so abrupt and scary. We were shipped in huge boats, together with our kids, furniture, dogs, cats and sheep. Then we realized we were being moved to the desert. The nearest water canal was 50 km away from where we were moved to.

What’s more, those who planned the move didn’t take into consideration our traditions or background.

Al-Masry: How so?

Abdel Karim: The government simply divided compensation to three types: families of two would stay in a one-room apartment; families of four in two-room apartments; and families of six or more in four-room apartments. These are not houses, they are military barracks.

When we first moved in, there were no ceilings. We used palm fronds to make ceilings with our own hands. We tried as much as we could–with the little resources available to us–to give life to the new homes. But they still look miserable, as you can see–especially given that the old Nubian homes were luxurious and beautifully designed.

All the houses used to face the Nile, and the architectural design took the weather into consideration so houses stored the warmth of the sun in the morning. All homes were at least 20 square meters or more and all had a guestroom. We used to build our homes using Nile clay — no cement or iron.

Al-Masry: Was the transition all bad, or were there also some positive aspects, such as greater access to public services?

Abdel Karim: The compensation was strange. Everyone used to own ten or more palm trees, each of which produced dates twice a year. We were compensated three piasters for each palm tree. Some people originally owned more than one house, but were nevertheless compensated with only one. In general, the compensation was very unfair and much of it has yet to be provided.

Al-Masry: What did you expect?

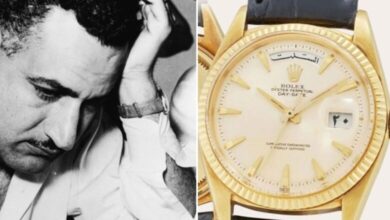

Abdel Karim: I expected a lot. Late president Gamal Abdel Nasser promised us that we would lead much better lives, and we all believed him. I remember a meeting he had here with our leader, Maher Ismail. It was attended by many leading figures. Thousands of people came. The president came by helicopter and landed near the house of the mayor, Tawfeek Rashwan, where he stayed.

Nasser was both loved and feared. People were scared when Maher Ismail–one of the few people that spoke Arabic then, because we all used to speak Nubian–stood up and said, "Welcome to Nubia, Mr. president–if you’re unfair to us, you’ll be judged by God." The president then answered him with these unforgettable words: "We, the leaders of the revolution, will all work to pull the Nubians together so they can lead happy and prosperous lives."

Al-Masry: So you resented Nasser for not keeping his promises?

Abdel Karim: On the contrary, we loved Nasser. It’s not his fault. It’s the mistake of those in power. He gave orders and people misunderstood them. When he died, a delegation of more than 100 Nubians traveled all the way to Cairo to attend his funeral.

Al-Masry: Do you remember the day you left your old home?

Abdel Karim: Very much. I was 18 at that time. I got up one morning and found big lorries outside or house moving everything, moving our possessions to the port. There were also huge ships waiting to move us. It was so chaotic–for the first time in my life, I saw people quarreling, snapping at one another.

You would find people, animals, furniture, children and personal belongings on the same ship. It was hard for everyone, especially the children. Almost all of them died.

Al-Masry: Did you know any of them personally?

Abdel Karim: My two younger brothers, my cousins–everyone I knew that was six years old or younger. They all died from the pollution and malnutrition.

Al-Masry: Is there a particular scene you would like to describe?

Abdel Karim: When we arrived to "New Nubia," the overseer of the housing project was standing there with a stick in his hand, carrying cards with our names on them. He walked, and all of us followed him. He shouted out our names. "Ahmed Abdallah, you go to this house," he shouted, brandishing his stick. It was cruel and inhumane. Now all of our leaders have either died from the humiliation or left Egypt.

Al-Masry: Did you ever try returning to what you once called home?

Abdel Karim: Yes. Six months after we moved, we went back to see what had happened. The water had risen to envelop our homes, palm trees, mosques. Everything was half submerged water. It was the saddest thing I ever saw.