News of Mahgoub Omar’s death on Saturday was largely drowned out by the intensive coverage of the death of Pope Shenouda III.

But a long obituary by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas syndicated in a number of Arabic newspapers has helped the news of his death claim more space in the media, prompting outlets to publish profiles for this rare breed of fighter who adamantly believed in armed struggle against Israel. Omar never gave up on his dream of an independent Palestinian state.

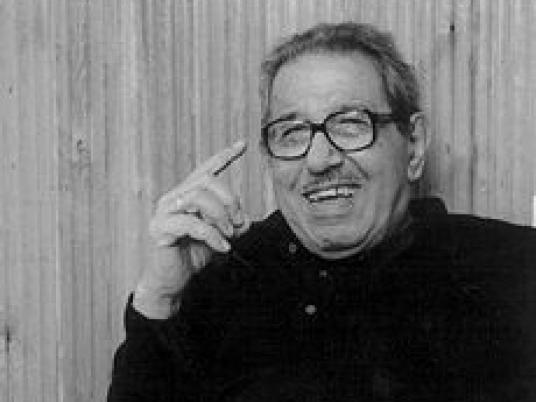

Raouf Nazmy, alias Mahgoub Omar, was born in the Upper Egyptian governorate of Minya in 1932. He graduated from the Faculty of Medicine and joined the Egyptian Communist Party, Al-Raya, which was established in the early 1950s.

Like many radical leftists, Omar rejected the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser, particularly its suppression of liberties, and like many communists, Omar did several stints in prison because of his beliefs.

He was jailed in 1954, when the security apparatus of Egypt’s post-coup rulers found that he had contacts with prominent Muslim Brotherhood figure Sayyid Qutb.

He was arrested along with many other communists in 1959, spending five years in prison. Unlike many leftists who adopted a conciliatory approach with Nasser, Omar remained critical of him. He was arrested for the third time in 1966.

After he was discharged from prison, Omar decided to focus his energy on anti-colonial movements, which had always been close to his heart.

He departed to Algeria, where he worked as a physician and trained in the Fatah movement’s camps in Algeria.

After his death, many news reports claimed falsely that he was part of the Algerian national movement. But Iman Yahia, a leftist activist and university professor, told Egypt Independent that those reports are completely false since Omar was in Algeria training as a fighter for the Palestinian national movement.

After Algeria, Omar’s next destination was Jordan. He joined Palestinian freedom fighters following the 1967 war.

It was then that Nazmy chose to go by the nom de guerre Mahgoub Omar. Even though he was Christian, he chose a Muslim name. Indeed, many Egyptians who joined the Palestinian resistance movement did not care much about religious identification.

Omar worked with the Palestinian resistance in Jordan until 1970, when Palestinian freedom fighters were attacked by King Hussein of Jordan in what came to be known as Black September. Thousands of Palestinians were killed and the Palestinian Liberation Organization was expelled from the country.

Omar became well-known after he saved the lives of dozens of injured Palestinians. He then wrote a book under the title, “The Story of Ashrafiyeh Hospital During the Events of September in Amman.”

“Human beings themselves changed in those days; all social masks fell while simple and unknown champions rose,” he wrote.

The center of Palestinian resistance then moved to Lebanon and Omar went with it. He was in touch with some of the most prominent members of the Palestinian resistance movement, including Khalil al-Wazir, one of founders of the Fatah movement who was assassinated by Israel in Tunisia.

Omar was also close to Palestinian Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat.

In Lebanon in 1975, he wrote one of his most famous books about Palestine, “A Conversation in the Shadow of Guns: History, Nation and Class.”

In his work, Omar was careful to distinguish between Zionism and Judaism, often writing that the Arab world could coexist peacefully with Jews, but not with a self-proclaimed Jewish state that has its origins in European colonialism.

He lived, struggled and wrote in defense of what he saw as people’s right to coexistence.

He was one of the writers of Arafat’s famous speech to the United Nations in 1974. The speech ended with the statement, “Today I have come bearing an olive branch and a freedom fighter’s gun. Do not let the olive branch fall from my hand. I repeat: do not let the olive branch fall from my hand.”

Omar returned to Egypt after the Palestinian resistance left Lebanon in 1982. He wrote prodigiously in defense of the Palestinian cause.

In its obituary, the Fatah movement said Omar “had a weekly article in the Egyptian newspaper Al-Shaab, which has helped a lot in enlightening the public and shaping Egyptian and Arab public opinion about the Palestinian issue and its international repercussions.”

Yahia, who had been close to Omar for nearly three decades, remains amazed by Omar.

“In 1954, he was arrested over charges of establishing a radio station on a truck. In Lebanon and Jordan he was an armed fighter. He wrote and translated poems and plays that were staged in Palestinian refugee camps. He treated the injured fighters and residents, working both as a doctor and a nurse. He established a publishing house to publish children’s books. He supervised nurseries for children at camps,” Yahia says.

“In his youth, he was a saint among his colleagues in prison. In his middle age, he was a fighter, with and without bullets. As an old man, he stood firm in the face of the toughest crises,” says Yahia.