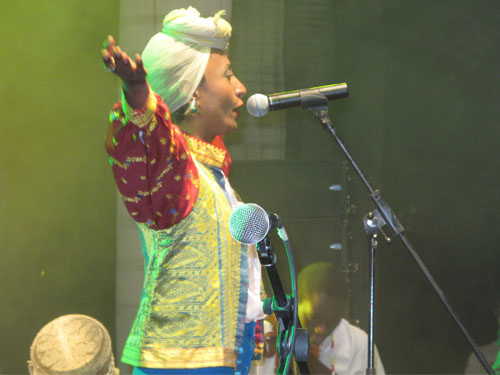

“My southerners, my southerners,” sang Egyptian musician Dina El Wedidi during the closing set of The Nile Project's concert in Al Azhar Park Thursday evening. The song — an ode to her southern neighbors along the Nile basin — kicked off with fellow Egyptian Hazem Shaheen hypnotically plucking his oud in the traditional Arabic maqam scale.

Within moments, they were joined by a riveting onset of percussions spreading from Nubian riqq players to tablah players from Sudan. The song culminated with a magnificent saxophone solo by Ethiopian musician Jorga Mesfin — his ability to play off the percussions caused an energy-filled, uproar of rhythmic clapping and dancing from the audience. And for a short evening in time, nothing else existed but the beautiful sounds of perfectly collaborated music from the various countries along the Nile basin.

Co-founded by Egyptian ethnomusicologist Mina Girgis and Ethiopian musician and activist, Meklit Hadero, The Nile Project is a cross-cultural musical collaboration initiative that seeks to address cultural and environmental issues rooted in the Nile basin. By using an innovative approach that combines music, informal education, and an enterprise platform, the project’s mission is to inspire, educate, and empower Nile citizens to work together in hopes of fostering a more sustainable river system.

“You know, there are 400 million people who share the Nile,” says Girgis, “It has a complex cultural landscape to navigate, and so the idea is really to develop qualitative measures that allow us to better understand each other. We are in a time of transition in Egypt, and we must begin cultivating our relationship with our southern neighbors. After all, we are African.”

According to Girgis, the cross-cultural collaborations features a diverse collection of musicians, styles, and instruments from the eleven Nile countries including Congo DRC, Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, South Sudan, Sudan, and Egypt. One of its main goals is to expose local audiences to the cultures of their neighbors — through storytelling, the songs are meant to humanize relevant social and environmental challenges experienced by the various cultures along the river.

Living between San Francisco and Cairo, Girgis has been working in the field of ethnomusicology and art entrepreneurship for nearly 10 years. He has participated in the organization of several multicultural events including the Smithsonian Silk Road Festival in Washington, DC and the Farah El Bahr Euro-Mediterranean Festival in Alexandria. In 2009, he also founded the Zambaleta Institute in San Francisco, which he describes as a nonprofit community and school for world music and dance.

“Much of the inspiration for The Nile Project was based off the work I did with the Smithsonian Silk Road Festival,” explains Girgis. “The Silk Road project is basically a performing arts nonprofit initiative with cultural and educational missions that promote innovation and exchanges between cultures who traversed the historical Silk Road trade routes [which connected East, South, and Western Asia with the Mediterranean and European worlds, in addition to parts of North and East Africa].”

“But the idea only really came about after I attended an Ethiopian music concert with Meklit in San Francisco. I had just returned from Cairo and it seemed ridiculous to me that I had to go all the way to California just to regularly hear Ethiopian music. Especially because Ethiopia and Egypt are so close geographically,” says Girgis.

After speaking with Meklit about the idea, the two decided to move forward with developing a cross-cultural exchange project that would spread through both their native countries and the surrounding cultures within the Nile basin.

“This concept was especially relevant because it had a lot of value that went beyond musical exposure,” he says. “We have had twenty years of unhelpful dialogue that has done little to help us figure out all the challenges and issues we have when trying to cooperate around the Nile basin. It became clear that there was a real need for a healthier cultural dialogue between those cultures.”

He goes on to mention that many of the Nile basin challenges are not only environmental, but the root of the problems is actually based in the lack of human understanding between cultures. They soon realized that through music, they could help cultivate a new path for intercultural learning.

“By building platforms for musical exchanges and experiences, we can foster cultural empathy and hopefully inspire environmental curiosity to shift the Nile from a divisive geo-political argument to a uniting cultural and environmental conversation,” he says.

The project officially launched its activities this past January with a four-day workshop that brought together members from environmental organizations, in addition to entrepreneurs, innovators, and leaders working in the fields of relevance to the Nile Project. Together they engaged in a series of dialogue sessions to learn about the diverse cultural perspectives within the Nile basin — they also worked to engage with Aswan’s community, addressing the local concerns while also learning about the local river ecosystem.

Earlier this year, The Nile Project also kicked off its inaugural music residency program called the “Nile Gathering.” For two-weeks, the program brought together 18 musicians to form an ensemble of Nile basin musicians in order to compose, record, and perform new music aimed at inspiring cultural and environmental curiosity.

The musicians were scouted and selected by Girgis, Hadero and the project’s renowned music director, Miles Jay.

“Miles is also an ethnomusicologist who lived in and out of Egypt for six years. His role is to help create the creative space in the residencies, which allows for the musicians to teach each other, collaborate, and co-create songs. He makes sure all the right components are there to properly produce and collaborate,” says Girgis.

For local percussionist and music activist, Hany Bedair, the residency was “one of his best collaborative experiences to date.”

“It was a very full circle program,” says Bedair. “Every day would start with a lecture about each of the Nile basin countries — one day it would be Uganda, the next it would be Rwanda and so on. After the lectures, we would create small groups for organized jam sessions — in the end we produced and recorded nearly 22 tracks. That is pretty remarkable to do in only 14 days,” he adds.

For Wedidi, one of the best parts of the program was the time spent in Aswan and the knowledge she gained about a culture within her own country. She says, “Prior to this trip my knowledge of the Nile was so minimal — in Cairo we use the Nile for social gatherings, weddings or to march alongside while we are protesting. But in Aswan, they live with the Nile — they eat and drink from it, it is their main source of income. It was eye-opening.”

Following the residency program, the musicians performed a set of 18 tracks at the Aswan Culture Center, where the concert was extremely well received by the local audience. This past Thursday, the first round of the project reached its culmination with a high-energy performance at Al Azhar Park in front of nearly 1,500 audience members made up of cultural aficionados, artists, musicians, and activists.

“In the end, it is all about learning to listen. I think that is what we all took away from this, whether it is the participants, the instructors, or the audience. Listening is the basis for understanding,” says Wedidi.

The Nile Project is an ongoing series of workshops, performances, and collaborations. The tracks produced by the musicians will be available for download on the project’s website.

Correction: This article has been corrected to reflect that the idea of the Nile Project came to Girgis after he attended an Ethiopian concert with Meklit in San Francisco rather than a concert of Meklit's music. It has also been corrected to reflect that Miles Jay has lived in and out of Egypt for the past six years.