Nobody feels the joy of the Eid as much as children, and when we were children, we could hardly contain our excitement while waiting for it: pocket money, new outfits, new shoes. We would put on these valuable garments and go out to show them off to the other children of the neighborhood.

“We would also show off our mothers’ kahk (the Eid confection par excellence), all the different varieties, so that instead of one helping, each of us would get five or six. The last time I ate kahk was a long time ago. When I became diabetic I stopped eating sweets, though I had a liking for them.

“That is the way of life. You give up your pleasures one by one until there is nothing left, then you know it is time to go.

From “Naguib Mahfouz at Sidi Gaber: reflections of a Nobel laureate, 1994-2001,” by Naguib Mahfouz and Mohamed Salmawy.

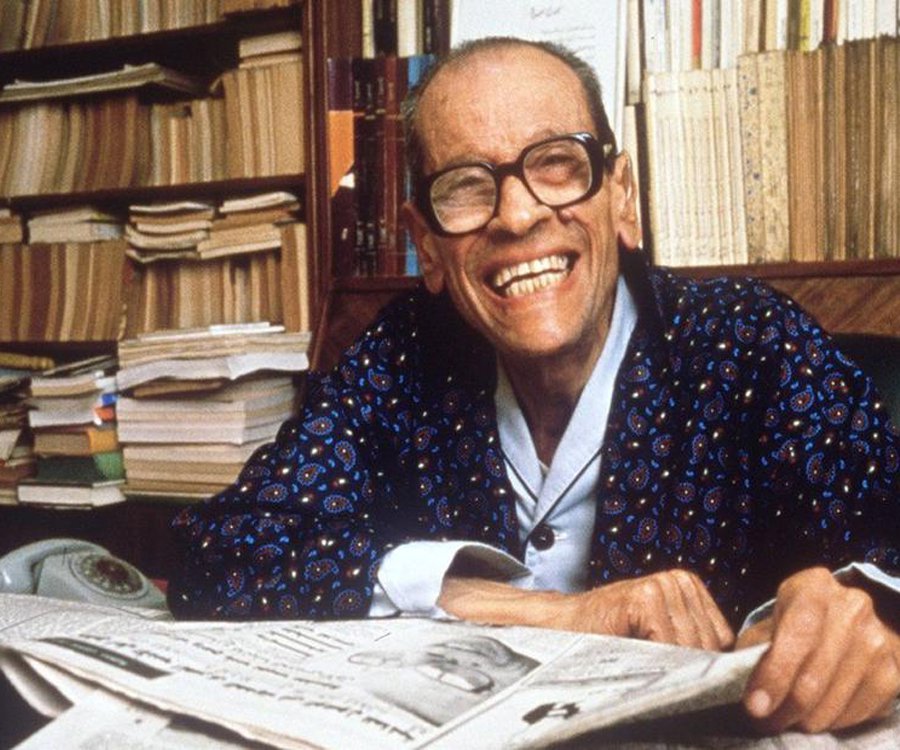

Naguib Mahfouz, who died on this day in 2006, gave unstintingly of his literary gifts. He wrote steadily through the 1930s and 1940s, pausing briefly at the opening of the 1950s after the 1952 revolution. He resumed and wrote on in the late 1950s to the 1980s. These were the years that Mahfouz produced the “Cairo Trilogy,” “Children of Gebelawi,” “Miramar,” “The Harafish" and “Arabian Nights and Days.” In 1988, at the age of 76, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in appreciation for these great novels. Six years later, he was stabbed in the neck by a fundamentalist and near-fatally wounded.

But although the nerves to Mahfouz’s right arm were permanently damaged and he would never pen another big novel, he never stopped working. At the age of 83, as Mohamed Salmawy writes in the introduction to “Naguib Mahfouz at Sidi Gaber,” the master learned how to write all over again. But the injury dogged him, and Mahfouz was only able to work for a short time each day. He no longer had the endurance for broad, expansive novels.

So in his last years, Mahfouz embraced a new genre: the exceptionally short and evocative dream story. Mahfouz’s arm was no longer good for the extensive crossing out and rewriting that he had once done. He would think through his stories, revise them in his head, and then memorize the version he would dictate to Sabry Hafez. His small, haunting, night-thoughts ran in “Nisf al-Donya” magazine as “Dreams of Convalescence” and have been translated into English by Raymond Stock. They were published sequentially as “The Dreams” and “Dreams of Departure.”

The dreams are spare renderings of his memories and nightmares, his early loves and his fears of death, muggings and attacks. Dream 107 is an ambiguous “prayer for the dead” that follows the funeral of a novelist renowned for his bad luck, quite different from Mahfouz, as “hardly a single reader knew his writings.” But things turn out – perhaps well – for the author, as “so many people came to take part or just to look on that when the procession reached the cemetery, it was the largest procession ever seen on such an occasion. By the time night fell, the deceased’s name was on everyone’s lips.”

In his final years, Mahfouz also continued to meet with a circle of literary friends and acquaintances. His weekly column for Al-Ahram became a conversation with Mohamed Salmawy, and these conversations were collected in the volume “Naguib Mahfouz at Sidi Gaber.” The columns were also short, evocative descriptions of wide-ranging topics such as Mahfouz’s physiotherapy, his experience with literary fame, birthdays, Eids, his childhood and his later years.

Salmawy even took pains to document Mahfouz’s final few weeks in the hospital, after a fall at home caused the literary master to hit his head. Salmawy’s narrative of the author’s last weeks, “The Last Station: Naguib Mahfouz Looking Back” (2007), shares many intimate moments.

Although the book was penned by Salmawy, it too is one of Mahfouz’s final gifts: Mahfouz continued to share his life and thoughts with others right up until he was gone.