KP.2 — one of the so-called FLiRT variants — has overtaken JN.1 to become the dominant coronavirus variant in the United States, according to data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data through May 11 shows that it’s responsible for more than a quarter of cases in the country, which is nearly twice as many as JN.1. A related variant, KP.1.1, has caused about 7 percent of cases, CDC data shows.

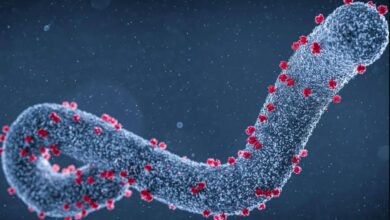

FLiRT variants are offshoots of the JN.1 variant — all part of the broader Omicron family — that caused this winter’s wave. The acronym in the name refers to the locations of the amino acid mutations that the virus has picked up — some in places that help it evade the body’s immune response and others that help it become more transmissible.

Covid-19 variants are “accumulating mutations that do one of two things: They either cause antibodies that you’ve accumulated from vaccination or infection to no longer bind to the to the virus — we call that escape from immunity — or they increase the strength in which the viruses bind to cells,” said Dr. Andy Pekosz, a virologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

This has become a familiar pattern in the way the virus that causes Covid-19 continues to evolve, but experts say we still don’t know enough to predict exactly where the changes will occur next or how they will affect the way the virus moves through the population.

The mutations of the FLiRT variants make increased transmissibility — and a possible summer wave — a real threat. Covid-19 is settling into some seasonal patterns, which have included a summer bump in years past, but the exact level of risk for this year is unclear.

“We’ve had some variants in the past that start out kind of strong and then don’t take over. These subvariants could progressively become dominant, or they could get up to accounting for somewhere between 20 percent and 40 percent of the cases and then just stay there. We just have to see,” said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University. “The virus continues to be in charge. It’s going to tell us what it’s going to do. All of our crystal balls are rather cloudy.”

Covid-19 surveillance has scaled back significantly since the US public health emergency ended a year ago, which also adds to the uncertainty. But the data that is available is consistent. For now, wastewater surveillance suggests that viral activity is very low and decreasing in all regions of the country, and Covid-19 hospitalization rates remain extremely low.

“We learned from the laboratories that FLiRT variants appeared, so far, to be as transmissible as the other Omicron subvariants, which means they’re really quite contagious. But they do not appear to be producing more severe disease or any sort of illness that’s distinctive from the point of view of clinical presentation symptoms,” Schaffner said.

As of May 1, the requirement for all hospitals to report Covid-19 data to the federal government has expired. But Schaffner’s Vanderbilt University Medical Center is part of a CDC-run surveillance network that continues to track trends based on a sample of hospitals that cover about 10 percent of the US population. Covid-19 hospitalization rates have fallen from nearly 8 new admissions for every 100,000 people in the first week of the year to about 1 new admission for every 100,000 people at the end of April, the data shows.

While the FLiRT variants pose some risk this summer, experts remain focused on what might happen in the fall.

“If I were to predict, I would say that this might result in a few extra cases, a small surge this summer. But it’s really going to be about which variant is around when we get to the fall,” Pekosz said. “The fall is probably when we should expect to see a surge of Covid cases. And if we have a variant around there that has a lot of these mutations that avoid immunity, then the potential in the fall to have a larger surge is greater.”

The fall and winter pose a greater risk because of the immunity that has built up in the population, he said.

“The virus now needs better conditions to transmit, and those better conditions to transmit are probably going to happen in the fall when weather gets cooler, people are spending more time indoors and they’re more likely to be in environments where respiratory virus transmission occurs more efficiently.”

Research published Wednesday in the medical journal JAMA is a reminder of the burden that Covid-19 continues to have in the US. This winter, while Covid-19 hospitalization rates were far lower than they were in earlier years, it was still deadlier than the flu. A study of thousands of hospital patients found that 5.7 percent of Covid-19 patients died, compared with 4.2 percent of those hospitalized for influenza. In other words, Covid-19 carried about a 35 percent higher risk of death than flu.

People who received the latest Covid-19 vaccine this past fall may still have some protection against the latest variants; that vaccine targeted a different strain but was found to be similarly effective against JN.1, and experts say that some of those benefits may extend to its FLiRT relatives. People who had a recent infection — especially since the start of the year, when JN.1 was prominent — may also have some protection. But immunity wanes over time.

In June, the US Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory committee will meet to discuss recommendations for the version of the Covid-19 vaccine that will be available this fall. The meeting was postponed by about three weeks in order to “allow for additional time to obtain surveillance data” to have “more up-to-date information when discussing and making recommendations,” according to a post on the federal agency’s website.

For now, experts say, risk remains relatively low.

“As with all things Covid, our outlook may change in a week or two. But at the moment, we’re in really a very good place — the best place we’ve been in for a long, long time,” Schaffner said.