Staring at grainy video footage of Jewish children marching to their freedom though the barbed-wire fences of the Auschwitz death camp, 79-year-old Vera Kriegel Grossman excitedly points a finger at the screen upon identifying a dark-haired girl in a dirty striped uniform as her 6-year-old self.

“I can’t believe that happened to me,” she said Wednesday. “I wasn’t a child there. I was all grown up … it was like I was 100 years old.”

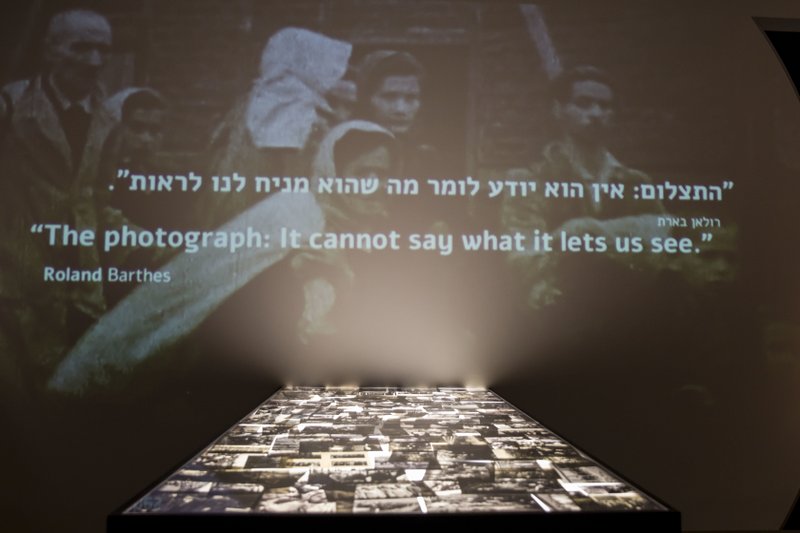

Archival footage shot by Auschwitz’s Soviet liberators is part of the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial’s latest exhibition, ahead of International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Saturday, exploring the power of photography during World War II. The 1,500 photographs and 13 films displayed come from various perspectives, victims and perpetrators alike, and look to offer today’s media-saturated visitors a new angle of looking at the horrors of the Holocaust.

Photography, perhaps more than anything else, has come to shape our memory of the Holocaust. The “Flashes of Memory” exhibit also offers a glimpse behind the lens — showing the actual cameras used, the photographers who took the pictures and their various motivations.

“The exhibit is aimed at the brain, not the heart,” said Daniel Uziel, its historical adviser. “We are asking the visitor to look beyond the image and examine the wider historical perspective.”

It includes Nazi-produced material that was part of their vast propaganda machine aimed at both enhancing their powerful image — such as Leni Riefenstahl’s famous films — and portraying the Jew as a decrepit, disease-infested yet sinister creature that was worthy of extermination. Also featured are the vivid photographs of American troops who freed the camps — depicting emaciated survivors, ash-filed crematoria, piles of corpses and the German civilians they forced to bury them so they couldn’t plead ignorance later. Besides serving as vital future evidence to try Nazi criminals, these were also aimed at re-educating the postwar German population and for domestic American consumption to legitimize the huge cost and sacrifice of joining the war.

Perhaps most insightful are the everyday photos taken by the Jewish victims themselves in various ghettos, some in the service of the Nazis and some in stealth in a desperate attempt to document the atrocities against them to serve as future proof. For example, Zvi Kadushin, an underground photographer in the Kovno ghetto, did so at great personal risk and produced essential documentation as a result.

“They used those images in order to present to the Germans their usefulness, their effectiveness,” said Uziel. “On the other hand, the Jews also seek, without permission, to document the crimes done by the Germans.”

Six million Jews were killed by German Nazis and their collaborators during the Holocaust, wiping out a third of world Jewry. Israel’s main Holocaust memorial day is in the spring — marking the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising — while the United Nations designated January 27 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day, commemorating the date of the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp in 1945.

That’s the day Grossman considers her second birthday, since she was delivered from the horrors of the camp to freedom.

“God opened the skies and sent us angels and rescued us,” she recalled, upon seeing the Soviet troops who later filmed her and the number tattooed on her arm. “I am happy it was documented.”

Grossman’s father was gassed and incinerated in the camp’s crematorium and she and her twin sister Olga were subjected to the ruthless experiments of the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele. She said her resistance to him is what kept her alive.

“I told myself what he would tell me to do I would do the opposite because he had no right to do these things to me,” she said. “He took away my body because he could do that but he couldn’t take away my mind.”

Far less eager to discuss their experiences were identical twins Lia Huber and Judith Barnea, both 80. Seeing the images, and themselves in them, brought back memories both had spent decades suppressing.

“It is buried inside our hearts and we don’t talk about it,” said Huber. “If you want to survive and continue life, you must continue and live with what you got and carry on.”

Photos from various chapters of the Nazi persecution of Jews were scattered across desks to depict the chaos in which they were taken. But it was the displaying of Nazi propaganda in the museum in particular that posed a difficult dilemma for Yad Vashem. Vivian Uria, the exhibit’s curator, said they tried to balance this with artifacts and testimony of survivors and victims who told their point of view. Ultimately, though, she said the visuals were essential and it was up to the viewer to look back at that dark era with a critical eye toward all those who documented it.

“The camera and its manipulative power have tremendous power and far-reaching influence,” she said. “Although photography pretends to reflect reality as it is, it is in fact an interpretation of it.”