New cancer drug cocktails set to reach the market in the next few years will test the limits of premium pricing for life-saving medicines, forcing company executives to consider fresh market strategies.

The growing reluctance of governments and private insurers to fund very expensive drugs – even remarkably effective ones – points to a showdown as manufacturers mix and match therapies that harness the immune system to fight tumors.

Several companies acknowledge discounts will be needed when drugs costing more than US$100,000 each are combined. That could give firms with multiple products in-house an edge over those having to negotiate pricing arrangements with partners.

Dozens of new cancer combinations will be launched over the next few years, with ones for lung cancer, melanoma and other solid tumors taking off strongly after 2018, drug company pipelines suggest.

Pricey immunotherapies, offering long-lasting responses, are already starting to change practice, as doctors use so-called checkpoint inhibitors like Merck's Keytruda and Bristol-Myers Squibb's Opdivo in melanoma and lung cancer.

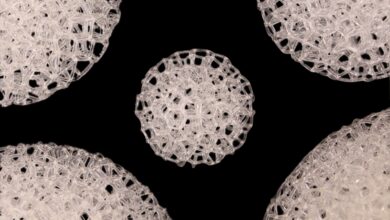

These drugs release the brakes on the immune system, allowing the body's defenses to recognize and destroy cancer cells.

But the real promise lies in combining treatments, either by using two checkpoint medicines together or by adding a different kind of drug. Both approaches will drive up prices.

Giving all U.S. patients whose cancer has metastasised, or spread, Opdivo and another Bristol immunotherapy called Yervoy, for example, would cost $174 billion, based on a combined list price of $295,000 for just under a year's treatment.

Cancer specialist Leonard Saltz, who presented the calculation in a speech to the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting two months ago, said the conclusion was obvious – these drugs cost too much.

Some pharmaceutical executives, while insisting they need a decent return for their risk-taking, admit he has a point.

"There's got to be a limit. One drug plus one drug can't equal the cost of two drugs," Novartis pharma head David Epstein told Reuters. "We recognize the need for oncology drug pricing to become more rational."

Roche, which is the world's biggest cancer drug supplier and is working on more immunotherapy combination trials than any other company, agrees there is a problem.

"We need to keep the system sustainable," said Roche Chief Executive Severin Schwan. "That is also in our interest."

Budget strains

The strains on healthcare budgets are clear. Worldwide cancer drug spending increased 10 percent in 2014 to $100 billion, up from $75 billion five years earlier, with oncology now accounting for 14.7 percent of total drug spending in Europe and 11.3 percent in the United States, according to IMS Health.

That has already prompted Roche to strike deals in parts of Europe capping costs per patient for its two targeted breast cancer drugs Perjeta and Herceptin, a template Schwan said was likely to be duplicated with the new immunotherapy products.

Other firms are pursuing other ways to keep prices affordable, with AstraZeneca preparing a cut-price version of one promising cocktail component.

The British drugmaker struck a deal last month to develop a cheap copy, or biosimilar, of Roche's established drug Avastin, which will go off patent at the end of the decade.

"Having the ability to include biosimilar Avastin will decrease the purchase price and give us a competitive advantage in terms of discounting," said Mondher Mahjoubi, AstraZeneca's head of oncology.

"The name of the game is going to be combinations in immuno-oncology and the more internal assets we have, the more flexibility we will have in pricing."

Most of the current buzz around checkpoint inhibitors centers on drugs blocking a protein known as Programmed Death receptor (PD-1), or a related one PD-L1, which tumors use to evade the body's natural defenses, plus another called CTLA-4.

But an alphabet soup of second-generation therapies is waiting in the wings, with names like OX40, LAG3 and TIM3, pointing to many new potential combinations.

It all means increasingly tough choices for healthcare providers, under intense pressure from patients and their families to provide access to modern treatments.

IMS data shows monthly cancer therapy costs have increased by 39 percent over the past 10 years in inflation-adjusted terms, similar to the 42 percent increase in overall response rates. But there has also been a 45 percent increase in the time that patients are on therapy, pushing up costs further.

Price is a growing issue for doctors, particularly in the United States where out-of-pocket costs can threaten to bankrupt some patients, as well as for pharmacy benefit managers, who negotiate drug prices for health plan members.

Investors are also watching developments closely.

"It's inevitable that prices will come under pressure, although because it is cancer and there is high unmet medical need, this might delay the squeeze," said Mirjam Heeb, co-manager of the JB Health Innovation Fund.