Nefertiti, the Egyptian queen, who is considered confused between her original homeland and a German residence.

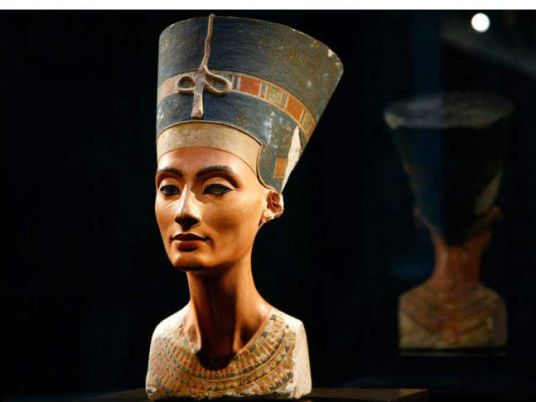

Amidst dim lights in a room decorated with ancient Greek paintings there is an area of 126 square meters with a height of 17 meters stands the statue of the ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti.

The monumental piece sits in the Neues Museum in Berlin, or it’s better known name “The Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection in Berlin”, looking in the direction of the statue Helios, the Greek god of the sun.

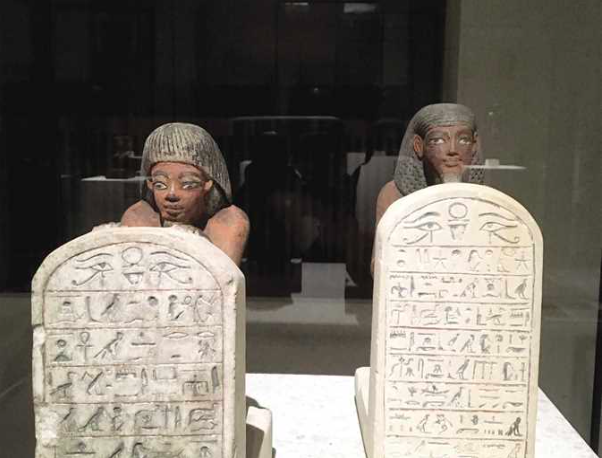

These monuments were also discovered in Egypt.

The Neues Museum in Berlin, Germany houses thousands of artifacts on an area of 8,000 square meters and is divided into four floors.

There are plenty of antiquities of Egypt’s ancient Pharaonic civilization and where you can wander between different eras.

The ground and first floors include a miniature model of a pyramid and its burial chamber. There are archaeological columns of temples and mummies dating back to 2500 BC.

The walls of the temples have hundreds of statues of different sizes, archaeological papyri, golden vessels, archaeological excavations and ancient Egyptian artifacts belonging to different eras.

This has become a well known attraction for German and foreign visitors.

With an estimated 1,500 people per day, the second floor where the statue of Queen Nefertiti currently resides is a room in the form of a dimly lit dome.

It has dedicated ventilation, supported by heaters on all sides.

The floor of the room has some dilapidated tiles, especially at the bottom of the statue, due to the many daily visits.

According to the museum’s official website, the statue was moved more than once.

The first move was after its discovery in 1912 under the ruins of the city of Akhetaton, which is now known as Tel el-Amarna.

The statue was displayed in the halls of German art collector James Simon, who funded the Tell el-Amarna archaeological mission for Germany, and allowed a few guests of honor to see the statue including, Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1920.

Simon gifted the bust to the royal Prussian art complex to be displayed in the Egyptian Antiquities Department in 1939 to protect it during the WW2.

After the war, the American occupation forces moved the statue to the city of Wiesbaden in central Germany.

In 1956 it was returned to Berlin and displayed in the Dahlem Museum, and in 1967 it was moved to the current Egyptian Museum in Berlin and was shown in the first floor. With the increase in the number of visitors, it was moved to the upper floor in 2005.

The statue of Queen Nefertiti, the most famous of the ancient Pharaonic queens, and the wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten, shows some restoration traces at the smashed ears, a small part missing from the blue crown, and in the golden chain on the shoulder.

The bust of Queen Nefertiti – like all pieces of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin – was legally removed out if Egypt, as the bust was found in the course of excavations authorized by the Egyptian Department of Antiquities, Olivia Zorn, deputy director of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, said.

According to Zorn it was customary at that time to divide archaeological discoveries.

There are no demands for recovery from the Egyptian government to the statue of Nefertiti which deserves a place in Berlin to represent the Egyptian cultural heritage, Zorn continued, in exclusive statements to Al-Masry Al-Youm.

The statue is dealt with by the museum with a great deal of care and respect, and it is visited on a daily basis by up to 1500 visitors, she added.

The area of Queen Nefertiti’s room is 126 square meters, and its height is approximately 17 meters, and the historical Greek and Roman decoration appears on the room due to the date of its establishment in 1850, as it was a display hall for Greek and Roman antiquities in that period, she said.

When the museum was restored due to World War II and opened in 2009, many Egyptian antiquities were transferred to it, and the decoration of the ancient Greek and Roman heritage was preserved as an integral part of the building’s history, Zorn added.

The Egyptian Museum in Berlin displays about 3,000 Egyptian artifacts, and about 250 archaeological documents written on papyrus and animal skin, on an area of about 3,600 square meters, divided into three floors, Zorn said.

The museum represents a comprehensive look at the continuity and changes of ancient Egyptian culture over 4,000 years, such as the worship of death, gods, kings, and daily life. The scientific history of Egyptology itself is also presented and clarified from depth for the first time through a collection of papyri in the museum’s antiquity library, she said.

Zorn explained that the reason for the presence of this large number of Egyptian antiquities in the Berlin Museum is the export of a large number of Egyptian antiquities to Berlin in 1823 through legal excavations – as she said – and King Friedrich Wilhelm III who helped increase its number after five years by buying a collection of Egyptian antiquities of about 1,600 pieces from the Italian businessman and art dealer Giuseppe Passalacqua, who was later appointed as the first director of the museum.

These Egyptian antiquities were displayed in the exhibition wing of Schloss Monbijou (north of the Spree River opposite the Bode Museum, which was destroyed in World War II).

The collection was greatly expanded by the acquisition of more than 1,500 artifacts from Prussian excavations led by Richard Lepsius in Egypt between 1842 and 1845, she added.

After a short time, the Ägyptisches Museum moved to the current Neues Museum, which was newly built, and it continued over the following decades.

Zorn emphasized that the expansion of antiquities holdings continued through purchases, donations, and excavations, especially archaeological excavations at Tell el-Amarna, funerary temples, the Temple of the Sun and others.

The holdings was greatly expanded between 1911 and 1914, especially with the statue of Nefertiti, which greatly enriched the collection.

Egyptian archaeologist and former antiquities minister Zahi Hawass, meanwhile, said the statue of Nefertiti was illegally exported in 1912 by the German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, who found it in Tell el-Amarna. At the time, there was an agreement to divide the finds equally between Egypt and the German excavation missions, with the prohibition of German missions taking any royal limestone statue, Hawass explained, adding the agreement did not apply to Queen Nefetiti’s statue.

When Borchardt found the statue of Nefertiti, he wrote in the discovery records that the statue was of gypsum stone to be able to smuggle the statue to Germany, Hawass said.

The statue was smuggled to Germany and remained hidden for ten years.

According to Hawass, Borchardt confessed later through his diary that the statue was made of limestone.

In 1933, Egypt demanded the return of the Nefertiti statue, because it is believed that the statue was illegally smuggled, but Hitler refused at that time to return the statue, and he displayed it in a museum in the capital.

Hawass added that he sent a letter in 2010 to the Berlin Museum, the British Museum, and the Louvre Museum requesting the borrowing of three artifacts: Nefertiti’s head, the Rosetta Stone, and the Planetarium for a period of three months, to display it at the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum, which was scheduled to open in 2015, but his requests were turned down.

“When they refused, I decided to make research committees about how Nefertiti’s head was taken out of Egypt.

The committees discovered that it was illegally smuggled. The Rosetta Stone was stolen at the time of the French Campaign and gifted to the British, and the Planetarium was stolen by an French antiquities thief, who cut off the roof of a temple in Dendera and sold it to the Louvre Museum,” he said, adding, “I sent the first letter signed by me in 2010 after I obtained the approval of the Minister of Culture and the Prime Minister of Egypt to Germany for the return of the statue, but the German party argued that the letter was not official, as it was not signed by the competent minister.”

“And when I was a minister for antiquities 2011 I was not lucky because of the period of the January 25 revolution,” he added.

Hawass said he launched a document weeks ago ti garner signatures demanding the return of Egyptian antiquities stolen in many countries.

He said the number of signatories has reached 150,000 people, most of whom are foreign nationals.

He continued: “When the number reaches one million people, I will start a popular campaign in which I demand the return of the Rosetta Stone, the Planetarium and the Nefertiti statue.”