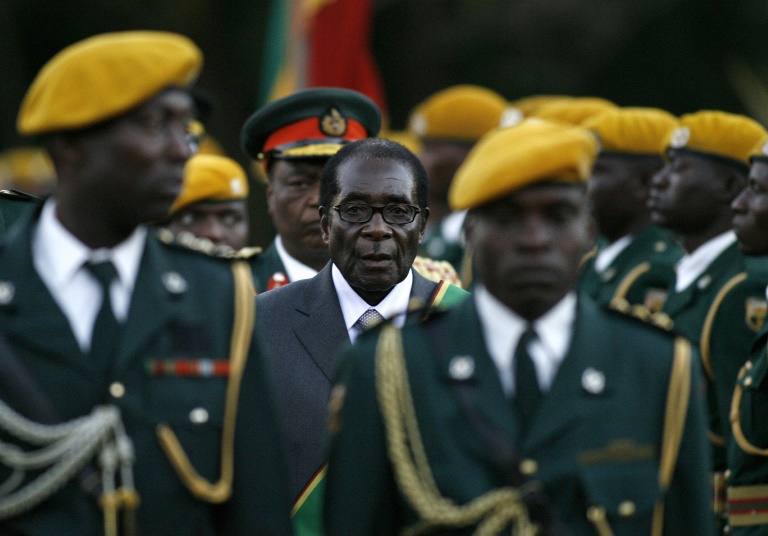

Once feared for the all-encompassing power he wielded in Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe died a “broken soul,” bereft at his downfall, his allies and relatives say.

Mugabe died in Singapore on Friday at the age of 95, nearly two months before the anniversary of the coup that forced him from power.

He had ruled the southern African country uninterrupted for 37 years and seven months.

During these long decades, Mugabe was Zimbabwe, and Zimbabwe was Mugabe.

But in his twilight years, he became vulnerable and helpless, according to relatives, allies and analysts.

Mugabe bowed to pressure and resigned on November 21, 2017 in a military-backed coup, ending an increasingly tyrannical rule that saw millions leave Zimbabwe to escape repression and economic ruin.

People close to him said the coup hit Mugabe very hard.

He never recovered from the shock that lieutenants whom he had groomed and trusted for years could betray him, they said.

“It was sudden,” his nephew Leo said. “He could not believe that those he trusted most turned again him.”

The coup was his “lowest moment — that period from November 2017 up to his last day… sometimes he would just sit there,” said Mugabe.

“A person who was used to waking up at 4 o’clock every morning, exercises, baths, goes to work and he has the whole country to look at, and suddenly that is abruptly brought to a halt — that is bound to affect.”

Mugabe’s health deteriorated incredibly quickly, he said.

‘Blind to reality’

The coup had been in the making for months but Mugabe was blind “to reality at that time,” said Ibbo Mandaza, one of the intellectuals who served in Mugabe’s government after independence.

“Mugabe’s last years were years of extreme vulnerability,” said Mandaza, now head of a thinktank, the Southern Africa Political Economy Series (SAPES) Trust.

Shortly after tanks rolled into the streets of Harare in a show of force, one of Mugabe’s allies who sought shelter at the leader’s house, was former education and information minister Jonathan Moyo.

Moyo, who spent time with Mugabe in the post-coup turbulence, said the once-feared autocrat dramatically changed.

“He became unusually introverted,” Moyo said. “He just became instantly withdrawn and non-engaging. He was deep in thought and palpably at a loss.”

He became a “broken soul, an obliterated soul and someone whose world collapsed in front of him and left him helpless,” Moyo said in a phone interview from Kenya where he fled after the coup.

Generals seized power days after Mugabe fired his vice president and there were mass street protests over concern Mugabe was positioning his wife Grace to succeed him.

After days of talks mediated by a Jesuit priest Fidelis Mukonori, Mugabe resigned.

Close to Mugabe for decades, Mukonori mediated most conflicts of Zimbabwean politics, starting in the 1970s with talks between guerrillas and colonial ruler Britain that led to independence in 1980.

Negotiating the exit of the man who ruled for nearly four decades “was not a walk in the park”, he told AFP at a cathedral on the outskirts of Harare.

“It was in the national interest that he decided to resign,” said Mukonori who later visited Mugabe several times after the coup.

‘Disappointed, angry’

During one visit, Mukonori told Mugabe that he had put on weight. Mugabe replied “‘of course why shouldn’t I, this is something quite good'”, said the priest adding he had a “beautiful smile, he looked calm”.

But others said he struggled to adjust to losing power.

The Catholic vicar general of the archdiocese of Harare, Kennedy Muguti, who used to go to Mugabe’s house to celebrate mass, said the former leader was “disappointed and angry” at the ouster but kept his faith.

“The last mass that he attended before he went to Singapore, I celebrated that mass,” Muguti said.

“He still had his faith even after the frustrations of what happened … the way he was removed from power; yes, he was a disappointed man, he was frustrated, he was angry.”

The anger was palpable during one of Mugabe’s last addresses to the media, on the eve of the July elections, just eight months after he was toppled.

Sitting on a chair, propped up by cushions, a bitter Mugabe vowed not to vote for people in the ruling ZANU-PF party who had “tormented” him.

“I can’t vote for ZANU-PF… what is left? I think it is just (Nelson) Chamisa,” he said referring to the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) leader.

Chamisa himself said that Mugabe, by hinting that he would vote for the opposition, “did realise some of his mistakes.

“There is a danger in overstaying in leadership,” Chamisa said. “You can’t succeed yourself successfully, successively.”