The specifics remain unclear, but Mohamed Morsy’s presidency is ushering in a new and unprecedented relationship between Egypt and its longtime ally the United States.

If the alliance between the countries remains as it has in past years, it would be the closest level of cooperation between the US and a democratically elected Arab president to-date.

Both sides are still feeling out the possibilities, but in its early stages, it appears to be an active relationship.

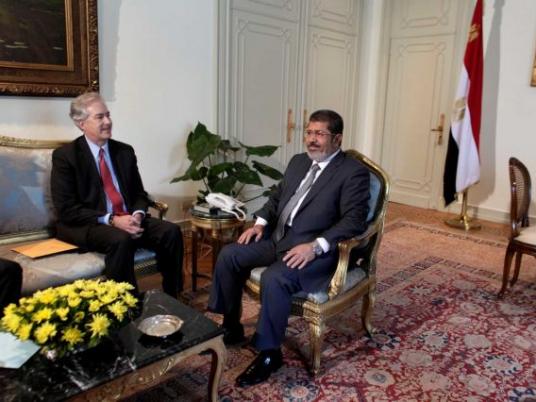

Deputy Secretary of State Bill Burns visited Cairo 6-8 July, bringing with him a message of congratulations from US President Barack Obama.

After what Burns called a “very constructive visit,” he said in a statement that Egyptians and the international community will be looking to Morsy and his cabinet to “take needed steps to advance national unity and build an inclusive government that embraces all of Egypt's faiths and respects the rights of women and secular members of society.”

Burns visit is soon to be followed by one from US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who will be in Cairo on 14 July.

In her most recent statements, after Morsy ordered the reassembly of the recently dissolved Parliament, Clinton has taken a cautionary tone.

She urged “intensive dialogue” between parties in power, and said democracy was about more than elections.

“It is about creating a vibrant, inclusive political dialogue, listening to civil (society), having good relations between civilian officials and military officials, where each is working to serve the interests of the citizens,” she said in a press conference in Hanoi, another stop on her trip.

But perhaps the strongest sign of real, fledgling cooperation is an invitation for Morsy to come to the US.

“President Obama extended an invitation to President Morsy to visit the United States when he attends the UN General Assembly in September,” presidential spokesperson Yasser Ali told Reuters after Morsy met with Burns in Cairo. Burns made no mention of a planned visit.

Before Morsy took office, top US foreign policy makers coming to Cairo met with Brotherhood leaders only after sitting down with the country’s military leaders, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. The White House reportedly called the Presidential Elections Committee and urged them to announce the results of the election “as soon as possible,” and Washington sources say that there’s an economic aid package being prepared with Morsy’s name on it if things go smoothly.

Brotherhood leaders returned the favor, visiting Washington in April and meeting with members of the high-profile National Security Council.

Hisham Kassem, a liberal political analyst who has had regular contact with American officials in the past said officials at the US Embassy in Cairo now have more direct lines of communication with Brotherhood members and less with liberal political players like himself.

But any relationship is still in the very early stages.

“Right now, everyone is polite, they seem to be negotiating civilly,” said Samer Shehata, a professor of Arab politics at Georgetown University in Washington.

In statements US officials have been congratulatory, stressing the importance of Morsy’s democratic election as the real milestone.

Under former President Hosni Mubarak, many Egyptians felt that the United States pursued its own interests at the expense of bolstering a dictatorial regime. Many also felt betrayed by their own government’s alliance with Israel at the behest of the US government.

In his speech given to thousands of supporters in Tahrir Square before he was officially sworn in, Morsy said he would improve relations with Egypt’s neighbors and abide by existing international agreements. But under him, he was sure to point out, relationships will be based on respect for Egypt and the will of the people.

A new way of operating

Under Mubarak, US-Egypt foreign policy happened almost exclusively behind closed doors, often between intelligence officials and the military, rather than diplomats, from the two countries.

If the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces and intelligence agencies remain as intact and robust as they were in past years, Shehata said, the US could bypass the president for back channels.

Public diplomacy presents a greater opportunity for diplomatic stumbles. What might have been a short conversation behind closed doors can turn into international controversy.

Morsy might have made his first misstep in his spirited Tahrir speech after noticing a banner calling for the release of Omar Abdel Rahman, the blind sheikh who was convicted of helping plan an attack on the World Trade Center in New York City in 1993.

In an apparently off-the-cuff remark, Morsy said he would work for his release. US media headlined stories about Morsy’s speech that he hoped to remove a convicted terrorist from US soil. In a TV interview in Switzerland, US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton responded by saying that the evidence against Abdel Rahman is very clearly incriminating.

Morsy likely already knows that calls for the release of the “blind sheikh,” as he is commonly known, are unlikely to be heeded by American ears, experts say.

The important thing is it seems both sides are ready and willing to engage with the other, Shehata and Kassem said.

“The Americans realize there’s a new game in town,” said Shehata. “They’ve come to the realization that they can do business with [the Muslim Brotherhood].”

Brotherhood leaders are likely to take a similar, matter-of-fact approach.

“They’re pragmatic and realistic,” he said. “I think these considerations will far outweigh their considerations in the short-term.”

The Americans favored a Morsy win in the first place, Shehata said, because it would mean less unrest after the results. A transition to a democratically elected president such as Morsy has been their call from the last days before Mubarak stepped down, he said.

Flashpoints

Aside from rhetorical blunders, there are points of contention that will arise between the US and the Muslim Brotherhood. How the Camp David Accords that maintain peace between Israel and Egypt, a loose security situation in the Sinai, and issues of personal rights or religious freedoms are dealt with could raise hackles on both sides.

The possibility of a change in leadership in Washington, with a US presidential election scheduled for November, could also shift the balance. If President Barack Obama does not win a second term, US support of Israel could get even stauncher and be particularly hostile to any renegotiation of the Camp David Accords that Brotherhood leaders have called for in the past.

Obama’s opponent, Mitt Romney, has spoken openly of how he would reverse the policies of Obama administration that he calls pro-Palestinian.

“The current administration has distanced itself from Israel and visibly warmed to the Palestinian cause,” he said in his speech to a pro-Israel lobby group in March. Romney has called himself a close friend of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

And there are some in Washington who see the Muslim Brotherhood as a serious threat to Israeli and regional security. Many Americans have trouble believing the group has completely left behind its former use of violent tactics, which it formally abandoned decades ago.

Eric Trager, a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, a pro-Israel think tank, said that the Brotherhood has been speaking out of both sides of its mouth, telling officials in DC what they want to hear, but repeatedly using hostilities in their own Arab-language releases and TV statements, and saying they believe that American intelligence committed the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001, not Al-Qaeda.

Trager, who says he consults with top US officials and has conducted dozens of interviews with top Brotherhood officials, including Morsy, criticizes what he says are some US intellectuals and policy makers’ attempts “to whitewash” a group with an inherently dangerous ideology.

“As Americans, we don’t, and shouldn’t, let conspiracy theorists dictate American interests,” he told Egypt Independent.

He said American officials need clear guarantees about the Camp David accords before embarking on any sort of cooperation.

If Morsy can’t give them, Trager said, “then the US should have to be prepared to let Egypt try and make it on its own.”