On 6 December, the president’s office issued a decision setting fines for the illegal dumping of construction waste and littering. Published together with tax hikes that caused a stir and were quickly postponed, these laws on public hygiene didn’t cause a similar fuss. But several right groups have criticized them nonetheless.

The presidential decision on hygiene stipulates that those caught dumping construction waste will be fined between LE1,000 and LE2,000, while those caught littering will be charged between LE500 and LE2,000. But if the violator manages to reach a settlement with local police, the fine can be reduced to LE500 for construction waste dumping or LE200 for littering.

The new law essentially replaces a harsher one from 1994, which punished similar offenses not only with fines ranging from LE1,000 to LE20,000, but also threatened recidivists with imprisonment and offered no possibilities for settlements.

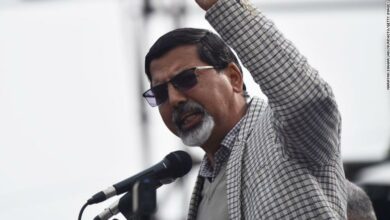

This move is quite surprising, says Mohamed Nagi, director of the Habi Center for Environmental Rights.

“The fines for littering are not the problem. The problem is that we lack designated areas and transportation to collect the garbage. This has to be tackled by searching for structural solutions.”

He explains that the situation was better 10 years ago, before the government replaced most of Cairo’s informal garbage pickers (zabaleen) with workers from multinational companies, who have not been as efficient in collecting garbage. Some multinationals have pulled out, but others are still working alongside the informal garbage collectors. No one is managing the entire system, and garbage continues to litter the streets in most Cairo neighborhoods.

Nagi says that while chaos has increased since the revolution, President Mohamed Morsy has not solved anything on the issue and “just aims to collect money.”

“Except for his big and expensive one-off ‘Clean Homeland’ campaign, Morsy hasn’t shown any interest in reforming the system,” says Ezzat Naem Guindy, a representative of the zabaleen for the Spirit of Youth Association. “Or shall we wait for the contracts with the multinationals to end in 2017?”

But the biggest question, according to Nagi, is why Morsy amended the law on littering with an exceptional decree.

“These declarations have a very specific character; they can’t be abrogated and stand above all other legislation. It’s as if [Morsy’s] scared someone will try to change them again,” he says.

Nagi compares these decisions with the jibaya, a tax traditionally used by Islamic rulers that urgently need cash.

“In absence of a functioning system, any talk of tightening sanctions becomes talk about collecting money and [doesn’t] deal with the problem,” he continues.

“Morsy tries to appeal to the middle class by showing that he is fighting chaos,” says Amr Adly of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, mentioning the president’s tough attitude toward street vendors. “In his 100 days program he wanted to restore order, but without spending his energy on reform. This is similar; his decisions are inconsistent and incomprehensible.”

Moreover, none of those who stood to be affected by the presidential decisions were consulted, even on the aborted tax hikes, he adds.

Negotiating settlements with local police seems to be the most contentious aspect of this new law. “If you tell the police I’m sorry, I won’t do it again, and here take LE200, is this really going to solve the problem?” Nagi asks.

The new decisions haven’t yet been implemented, likely to avoid provoking outrage in the critical days of the constitutional referendum.

“This kind of policy will only increase bribes and corruption,” Adly says.