The Synod of Bishops' Special Assembly for the Middle East was held from 10 to 24 October to discuss pressing issues pertaining to Christians in the region.

The synod brought together in Rome all the Catholic Church's bishops and patriarchs in the Middle East, church representatives from other continents, and several cardinals. In addition, over 30 experts and observers on Middle East affairs took part in the event.

“The problems affecting the Christians of the Middle East are huge, from Morocco to Iran, including Turkey," said Rafic Greiche, spokesman for the Catholic Church in Egypt, who participated at the synod. " We wanted to achieve a feeling of solidarity with the pope and with the universal church–and we really felt this at the synod.”

Annie Laurent, a Paris-based political scientist who specializes in Middle Eastern affairs, said: “What prompted [Catholic Pope] Benedict XVI’s decision to hold the synod was his trip to the Middle East in May 2009. This led him to observe more accurately the situation of the Christians, especially in Palestine.”

“For the last few years, Rome has become increasingly worried about the situation in the Middle East,” Laurent added.

According to one anonymous observer in Cairo, the synod was prompted "by the massive emigration of Christian populations from Iraq, whose numbers have decreased over the last 20 years from 1.5 million to 400,000–a full two thirds of them have left.”

Background documents prepared ahead of the synod saw the issue of migration primarily as the product of political conflicts in Israel, Iraq and Lebanon. Greiche affirms that the Palestinian issue represents “the first problem from which all secondary problems of the Christians originate."

Recommendations issued by the synod called on civil authorities to enforce UN resolutions on “the return of [Palestinian] refugees [to what is now Israel] and the status of Jerusalem and the Holy Land." On the closing day of the event, the pope declared: “Peace is possible, peace is urgent.”

The fear of the growth of political Islam was seen as another issue of concern for the Christians of the region. “In Egypt, the amendment of Article 2 of the constitution in 1980, which made Islamic Law a main source of legislation, is seen by Christians as a threat to their existence within the country,” said the anonymous observer.

Recommendations issued at the synod also called for guaranteeing the freedom of thought.

“We're citizens equal to our Muslim brothers, not second-class citizens," said Greiche. "In Egypt, we just want to be free to build churches, with the same laws applying to everybody. We want civil legislation that respects our traditions and we ask for freedom of thought, which transcends freedom of religion.”

The integration of Christians into Middle Eastern society was also on the agenda. “The problem is that Christians withdraw from society,” said the anonymous observer. "Bishops invite them to engage in public life, but they require favorable conditions."

“It's very important that Christians do not withdraw into social, cultural and political ghettos,” explained Laurent. “Governments must look into the problem of Christians. The synod asked governments to accept and promote this participation."

“It's not a question of attacking Muslims,” said Greiche. "On the contrary, the synod wants Christians to serve society and to be active citizens. It wants Christians to favor dialogue, which represents the best way to make people live together and know each other.”

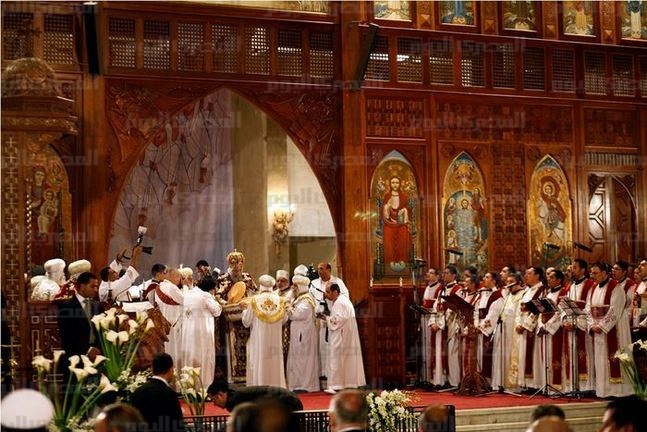

Egypt is home to some 300,000 Catholics and a large Coptic Christian minority estimated at roughly 10 percent of the country's population of 88 million. There are about 5.7 million Catholics living throughout the entire Middle East.