(CNN) – A tiny spacecraft with big implications for lunar exploration has launched.

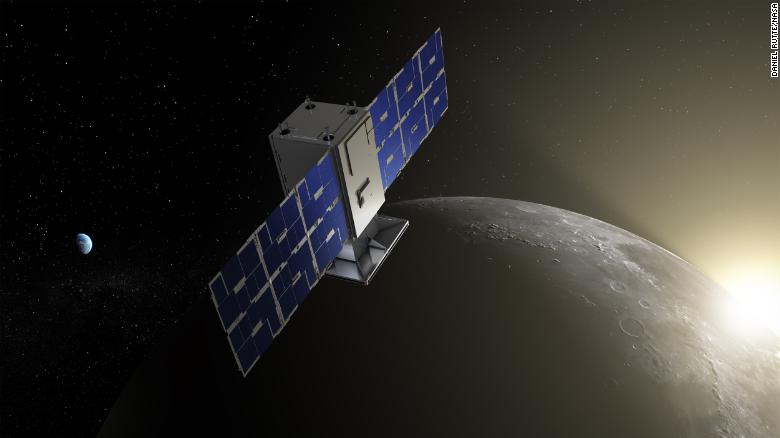

The miniscule satellite, called a CubeSat, is about the size of a microwave oven and weighs just 55 pounds (25 kilograms), but it will be the first to test out a unique, elliptical lunar orbit. The CubeSat will act as a pathfinder for Gateway, an orbiting lunar outpost that will serve as a way station between Earth and the moon for astronauts.

The orbit, which is called a near rectilinear halo orbit, is very elongated and provides stability for long-term missions while requiring little energy to maintain — which is exactly what the Gateway will need. The orbit exists at a balanced point in the gravities of the moon and Earth.

The mission, called the Cislunar Autonomous Positioning System Technology Operations and Navigation Experiment, and known as CAPSTONE, lifted off the launchpad Tuesday at 5:55 a.m. ET. The CubeSat launched aboard Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket from the company’s Launch Complex 1 in New Zealand.

It will reach the orbit point within three months and then spend the next six months in orbit. The spacecraft can provide more data about power and propulsion requirements for the Gateway.

The CubeSat’s orbit will bring the spacecraft within 1,000 miles (1,609.3 kilometers) of one lunar pole at its closest pass and within 43,500 miles (70,006.5 kilometers) from the other pole every seven days. Using this orbit will be more energy efficient for spacecraft flying to and from the Gateway since it requires less propulsion than more circular orbits.

The miniature spacecraft will also be used to test out communication capabilities with Earth from this orbit, which has the advantage of a clear view of Earth while also providing coverage for the lunar south pole — where the first Artemis astronauts are expected to land in 2025.

NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbit, which has been circling the moon for 13 years, will provide a reference point for CAPSTONE. The two spacecraft will communicate directly with each other, allowing teams on the ground to measure the distance between each one and home in on CAPSTONE’s exact location.

The collaboration between the two spacecraft can test CAPSTONE’s autonomous navigation software, called CAPS, or the Cislunar Autonomous Positioning System. If this software performs as expected, it could be used by future spacecraft without relying on tracking from Earth.

“The CAPSTONE mission is a valuable precursor not just for Gateway, but also for the Orion spacecraft and the Human Landing System,” said Nujoud Merancy, chief of NASA’s Exploration Mission Planning Office at Johnson Space Center in Houston. “Gateway and Orion will use the data from CAPSTONE to validate our model, which will be important for operations and planning for the future mission.”

Small satellites on big missions

The CAPSTONE mission is a rapid, low-cost demonstration with the intent to help lay a foundation for future small spacecraft, said Christopher Baker, the small spacecraft technology program executive at NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate.

Small missions that can be put together and launched quickly at lower cost means that they can take chances that larger, more expensive missions can’t.

“So often on a flight test, you learn as much, if not more, from failure than you do from success. We can afford to take more risk, knowing that there’s a probability of failure, but that we can accept that failure in order to move into advanced capabilities,” Baker said. “In this case, failure is an option.”

The lessons from smaller CubeSat missions can inform larger missions down the line — and CubeSats have already been setting out for more challenging destinations than low-Earth orbit.

When NASA’s InSight lander was on its nearly seven-month trip to Mars in 2018, it wasn’t alone. Two suitcase-size spacecraft, called MarCO, followed InSight on its journey. They were the first cube satellites to fly into deep space.

During InSight’s entry, descent and landing, the MarCO satellites received and transmitted communication from the lander to let NASA know that InSight was safely on the surface of the red planet. They were nicknamed EVE and WALL-E, for the robots from the 2008 Pixar film.

The fact that the tiny satellites made it to Mars, flying behind InSight through space, excited engineers. The CubeSats kept flying beyond Mars after InSight landed, but fell silent by the end of the year. But MarCO was an excellent test of how CubeSats can tag along on bigger missions.

These tiny but mighty spacecraft will again serve a supporting role in September, when the DART mission, or the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, will deliberately crash into the moonlet Dimorphos as it orbits near-Earth asteroid Didymos to change the motion of the asteroid in space.

The collision will be recorded by LICIACube, or Light Italian Cubesat for Imaging of Asteroids, a companion cube satellite provided by the Italian Space Agency. The briefcase-size CubeSat is traveling on DART, which launched in November 2021, and will be deployed from it prior to impact so it can record what happens. Three minutes after the impact, the CubeSat will fly by Dimorphos to capture images and video. The video of the impact will be streamed back to Earth.

The Artemis I mission will also carry three cereal box-size CubeSats that are hitching a ride to deep space. Separately, the tiny satellites will measure hydrogen at the moon’s south pole and map lunar water deposits, conduct a lunar flyby, and study particles and magnetic fields streaming from the sun.

More affordable missions

The CAPSTONE mission relies on NASA’s partnership with commercial companies like Rocket Lab, Stellar Exploration, Terran Orbital Corporation and Advanced Space. The lunar mission was built using a fixed-price small business innovative research contract — in under three years and for under $30 million.

Larger missions can cost billions of dollars. The Perseverance rover, currently exploring on Mars, cost more than $2 billion and the Artemis I mission has an estimated cost of $4.1 billion, according to an audit by the NASA Office of Inspector General.

These kinds of contracts can expand the opportunities for small, more affordable missions to the moon and other destinations while creating a framework for commercial support of future lunar operations, Baker said.

Baker’s hope is that small spacecraft missions can increase the pace of space exploration and scientific discovery — and CAPSTONE and other CubeSats are just the beginning.