At a commercial gallery in Zamalek, there is currently an exhibition of work by an Egyptian painter and writer who lives in New York. It consists of about two dozen pictures ranging date-wise from the early 1950s to 2012. The artist is Ahmed Morsi, the show “Metaphysics” and the space Gallery Misr.

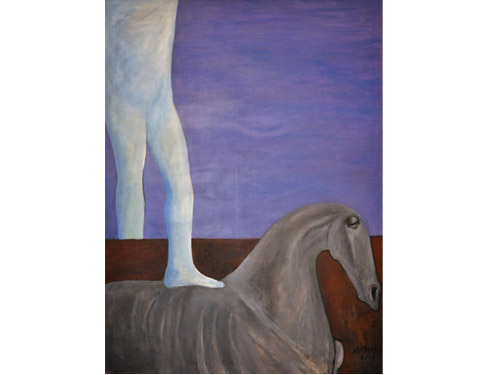

Most of the works are acrylic paintings. They tend to be melancholic in mood and have cold, mild colors — muted blues, greens and yellows. They are all centered around the human body, and the bodies all have similar stylized faces with large eyes, no foreheads and very thin, long noses. The features are somewhat reminiscent of those in old Coptic Fayoum portraits.

The pictorial elements in most of the paintings are birds, horses, fish and unclothed, amorphous male and female bodies. There is also the odd pyramid. These elements tend to float on empty backgrounds.

The style is generic: a bit surrealist, a bit symbolist, a bit cubist, a bit expressionist, a bit naive.

The more recent paintings have soft, fluffy brushstrokes, thinly applied pastel colors that glow slightly. They tend to be more simple and minimal than the older ones.

“Four Eyes” (2011), used as the image to promote the show, stands out as it has an up-to-date air about it, a simple clarity and, uniquely, depicts an unmistakably young person wearing distinguishable items of clothing. Unexpectedly, the figure also has four identical eyes that look directly at the viewer.

The works from the 1970s look grittier, with harder edges, sharper angles and thicker paint. “Face of a Woman” (1972) has a pleasant patina of dirt and shine on the lumps of its 1970s-style impasto. In a still life from 1975, a red fork seems to balance on its prongs on a fish.

In “Waiting for Godot” (2012), two clothed women have sad faces that each have a thin crack going through them, as does a pyramid that floats above. A small horse and a skeletal camel hover nearby. Perhaps it is suggesting, vaguely, that Egypt has a problem. Or perhaps it is just about “Waiting for Godot,” and the pyramid is incidental.

A couple of other paintings stand out as the least generic-looking. “Fishermen” from 1956 is a beach scene with six identical, monumental male figures and a couple of unusual spiky fish that have exactly the same eyes as the men. It is strange, and has an air of social realism.

“Global Telegram” (1984) is also intriguing — it is the only piece to have either collage or text in it. A small piece of paper that looks like a shrunken magazine cover is stuck in one corner. It says “RCA Global Telegram” on a banner at the top, and, underneath, a painting of a woman’s head — perhaps a late Picasso — is reproduced.

The rest of the painting is a larger, loose copy of the stuck-on element. Like “Fishermen” but unlike the rest of the paintings, the real world seems to have a bearing in “Global Telegram,” and both paintings are enigmatic.

But overall, the works in “Metaphysics” exemplify the kind of inoffensive paintings that can be seen in second-rate commercial galleries worldwide. They seem to be made not in competition with art in general but as the artist’s personal spare-time expressive outlet.

Thus there is a sense of isolation from the world, elements are repeated a lot, there is not much variation in theme or mood. The paintings do not seek to challenge the artist or the viewer; they are not trying to push anything forward.

If visitors read the two short texts in the lavishly produced booklet that accompanies it, they may laugh at the gap between the grandiose and nonsensical claims made for the paintings, and what the paintings actually are.

Art critic Jonathan Goodman writes: “Morsi is a painter of symbolic truth, of ancient timelessness, very late in the 20th century, as such, his work has small commerce with the deliberate dumbness and facile smugness of many artists working in New York.” He explains further, “Because his works symbolically [sic], Morsi has been able to envision a world in which a few chosen images — lovers and horses for the most part seems to stand outside time, as an impact comment on, and explicit manifestation of, the ritual sacredness of what we do.”

The other text, by poet Salah Awad, is equally baffling.

“It is capable with its simplicity to confuse the spectator by the gathering of its presence and non-presence if we want to borrow from Maurice Blanchot,” it says, adding that the “color blue, which occupies a large space in his works, according to its artistic path, is a witness to the non-existence of revelation.”

A danger with writing blurbs to accompany art, apart from limiting viewers’ potential interpretations of it, is that pompous and unrealistic descriptions can make the viewer lose sight of the more modest qualities that the work actually does have. In this case, the texts barely make sense, and the crude argument that many artists in New York are smugly dumb sounds irrelevant and petty.

Rather than offering revelations or intellectual feats, or exploring the possibilities of what art can be, “Metaphysics” is a record of one man’s enduring passion for painting, the works are gentle and have nice colors, and people will buy them to decorate their houses and hopefully love them.

Images courtesy of Gallery Misr

This piece appears in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.