As the Muslim Brotherhood strives to project the image of a moderate and democratic political organization, a book featuring the angry account of a former member has hit the market.

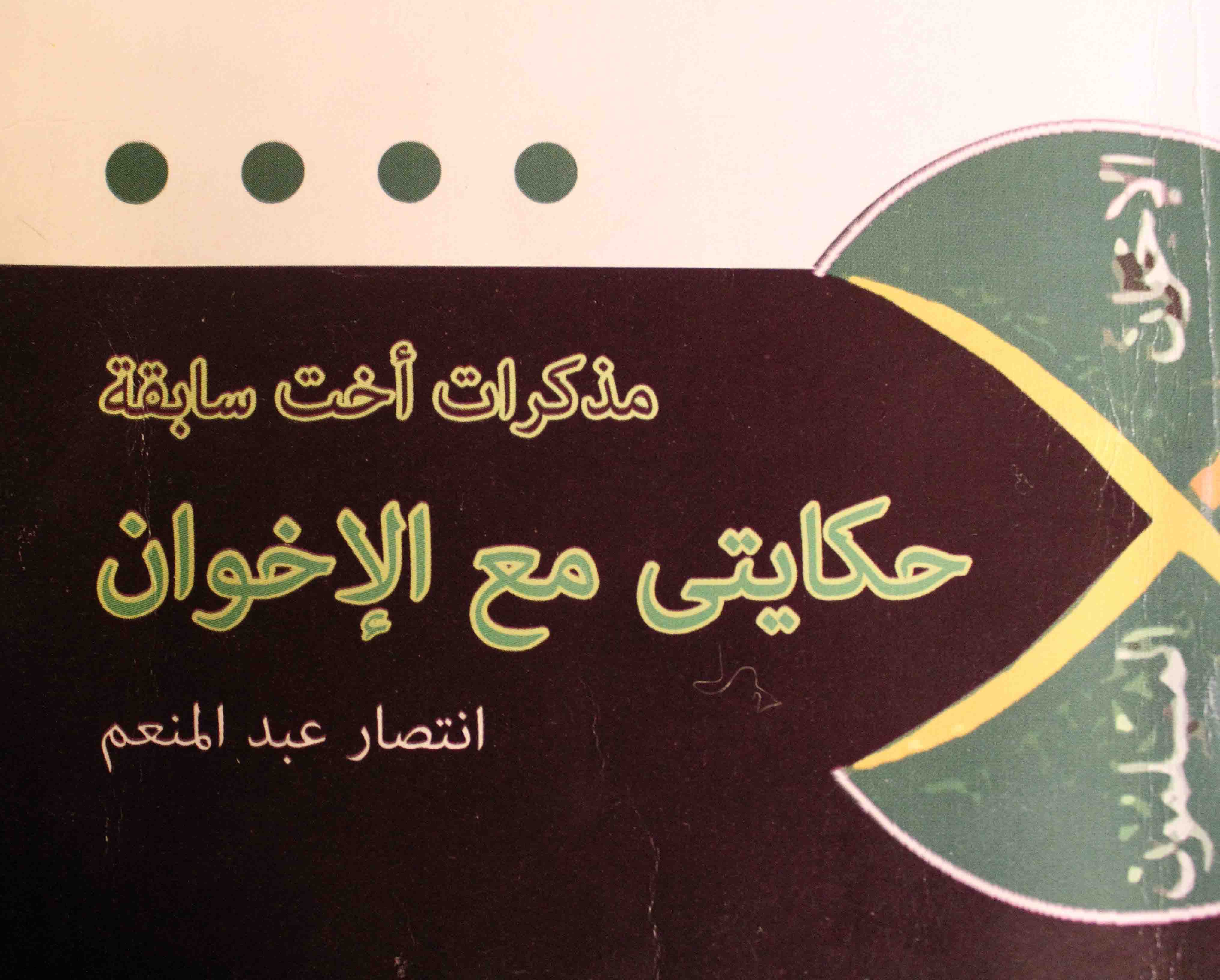

"The Memoirs of a Former Sister: My Story with the Muslim Brotherhood" is the testimony of Intissar Abdel Moneim, an Alexandria-based novelist and author. With a compelling style and sharp language, the book takes the reader on a journey exploring the internal politics of the 83-year-old organization, placing special emphasis on discrimination against female members.

Throughout her work, Abdel Moneim decries the sisters’ internalization of oppression as women are socialized in a way that compels them to accept male dominance within the organization — and the household.

Early in the book, Abdel Moneim condemns what could be interpreted as the Brotherhood’s exploitation of the permissibility of polygamy in Islam.

“One of the areas where the Brothers have exploited the idea of blind obedience and submission is polygamy,” she writes, adding that a brother would take second and third wives for no valid reason. “When the [first] wife complains, a session is held for her where other sisters would remind her of the importance of obedience, patience and submission to God’s will and to [the husband]’s will,” she writes.

To understand the roots of the subjugation of women, Abdel Moneim unpacks the writings of Hassan al-Banna, the group’s late founder. Here, the author summons her courage and puts forth a vehement critique of the group’s canonized leader, who is rarely questioned, even by the most vocal ex-brothers.

Banna's teachings sought to limit women to "catering to their husbands' desires and to reproduction," Abdel Moneim writes.

The book dismisses Banna's dictum that there is no need to invest heavily in girls' education and that women should be trained only to serve as housewives and mothers. Abdel Moneim feels that this sentiment is contradictory to true Islam.

“It is true that Islam says that a woman’s primary role is to raise children, but it does not say that this is her only role and that she should not do anything beyond it. Neither the Koran nor the Sunna [Prophet Mohamed’s sayings and deeds] nor the sayings of the prophet’s companions and successors barred her from learning any sciences. The matter has been left for her to decide, according to her needs and circumstances," writes Abdel Moneim.

She goes on to criticize Banna's insistence that men and women should be separated. With a scathingly sarcastic tone, the author argues that Banna’s view portrays humans as if they are mere animals who have little control over their impulses.

“You cannot by any logic perceive all people as mere female and male sex organs that roam the streets looking for the moment of intercourse like cats," the book reads. Abdel Moneim attributes Banna’s rigid outlook to his rural background.

This outlook still shapes the group’s perception of women’s roles within the organization and in the society at large. It justifies why the Muslim Sisters' division cannot operate independently from the Brothers, why no woman is admitted into the group's highest bodies, namely the Shura Council and the Guidance Bureau, and why the group will not acknowledge a woman's right to rule, according to the book.

This does not mean that the group never deviated from this ideology. In the lead-up to the 2005 parliamentary elections, it relied heavily on the sisters to campaign for male candidates, says Abdel Moneim.

“Nobody was saying then that women should be staying at home, raising children and beautifying themselves for their husbands. … All of a sudden women providing logistical support became crucial,” she writes sarcastically. To her, this deviation stemmed from the group’s lust for political power, which required mobilizing all its resources to win seats in the elections.

The book came out in the midst of Egypt's first post-Hosni Mubarak parliamentary poll. The Muslim Brotherhood has proven itself the most popular political faction and the key civilian player in the new order. The group has already risen as the largest bloc in the People’s Assembly by garnering nearly 40 percent of the seats. The Brotherhood is expected to achieve similar gains in the Shura Council vote scheduled to begin later this month.

Since Mubarak's ouster, the group has strived to assuage concerns about its political and social outlook by claiming that it holds a genuine belief in democracy and equality between all citizens regardless of their faith and gender. To prove that they had relinquished their gender and religious bias, the Brotherhood fielded Copts and women on their electoral lists. Yet, these attempts were unable to completely alleviate the fears of liberals and secularists that the group still flirts with a rigid Islamic outlook.

By the same critical token, the author bashes the Brotherhood’s internal dynamics, arguing that it is based on nepotism rather than merit. To substantiate her claim, she refers to her personal experience recounting that she was not easily admitted into the group because she was not the daughter, the sister or the wife of one of the Muslim Brotherhood's heroic or wealthy figures. For both men and women, such family ties are required to facilitate one’s upward mobility within the organization, according to Abdel Moneim.

Meanwhile, the author coins the phrase “the Muslim Brotherhood’s classism” to describe the full submission of rank-and-file members to their leaders. She borrows the analogy put forward by a former Muslim Brotherhood leader who drew parallels between the organization and an electricity-providing company that needs lots of workers (rank-and-file members) and few engineers.

“It is illogical for a worker to bypass his master or demand that his position be improved even if he proves himself,” Abdel Moneim writes. “Otherwise, he will be violating the group’s charter and instilling divisions. This is probably the Muslim Brotherhood’s interpretation of George Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm.’”

Although the book is presented as a memoir, it provides very little biographical information about the author. The reader finishes the book not knowing Abdel Moneim’s age, when and how she joined the Brotherhood and what year she left the group. Toward the middle of the book, the author implies that she became a sister after marrying a brother. Nothing is mentioned about this brother, who seemed to have joined the group with ease.

Yet the book has not failed to cause a stir. Earlier this month, the Muslim Brotherhood rushed to sue the privately owned Al-Fagr newspaper for running a sensational review of the book that accused the organization of abusing women sexually and politically.

Surprisingly enough, the group has declined to sue the book's author. In an interview with a local website, Mahmoud Ghazlan, the Brotherhood’s spokesperson, downplayed the book’s impact.

“The Muslim Brotherhood is much bigger than a woman or a man. We will not preoccupy ourselves with whoever leaves us, insults us or publishes a book," Ghazlan said.