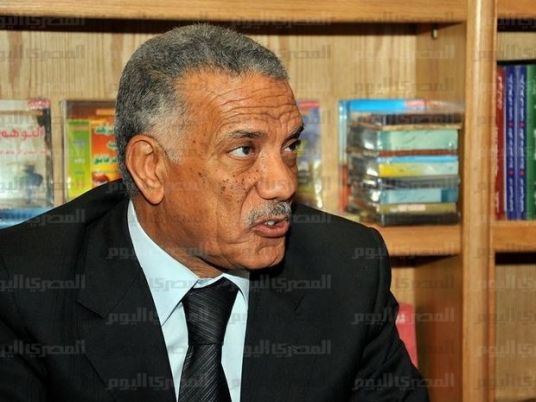

For decades, Hesham al-Bastawisi led the battle for the independence of the judiciary under toppled President Hosni Mubarak. For years, he labored under pressure from the former regime, bearing the brunt of government threats and coercion tactics.

But despite a blemish-free record and a struggle that has made him a widely respected judicial figure in Egypt, he has garnered little support as a presidential candidate. It seems his lack of political experience and humble attitude don’t fulfill the expectations of grandeur that many have for the country’s next president.

Battling with the regime

Bastawisi excelled right out of law school. After graduating in 1976, he was appointed as the judicial supervisor to customs police in Alexandria. After moving between courts, he was appointed to the secession court in Cairo, where he was elected to the court’s council in 1988. In 2000, Bastawisi was promoted to vice president of the secession court.

Since the start of his career, Bastawisi has been unwilling to participate in state crimes, which often depended on the implicit collusion of the judiciary.

In 1982, as a young judge overseeing the elections in the district of Menya al-Basal in Alexandria, Bastawisi canceled the elections in his district because of security intervention and rigging. He recounted in recent interviews how he got a phone call from a judicial source with a special pleading from Mubarak to reverse his decision, but he refused to comply.

In 2003, Bastawisi assisted as deputy head of the secession court in a ruling to annul the election in the district of Zaytoun, in which former Presidential Chief of Staff Zakariya Azmy, one of the most prominent figures of the old regime, had won through rigging. Again, state pressure was not able to convince Bastawisi to reverse his ruling.

During his four years on assignment as a judge in the United Arab Emirates starting 1992, Bastawisi was just as uncompromising when it came to the dignity of the judiciary.

Bastawisi reportedly received a note from a member of the UAE ruling family asking for a pardon for a defendant whose case he was seeing. Bastawisi responded with a note, writing “no intercession for anyone” — a saying with an Islamic reference stressing equality in justice.

Bastawisi also started a strike for Egyptian judges in the Emirates when two of their compatriots were suspended because of a verdict they issued that angered the ruling family. The sit-in continued despite royal pressure until the reinstatement of the two judges.

Bastawisi also suffered the consequences of confronting state intervention in the judiciary throughout his career. He was subjected to repeated travel bans, an alleged kidnap and defamation attempts. But it wasn’t until 2005 that Bastawisi had his fiercest battle with the regime.

In 2005, he was one of the leading figures of a judicial movement spearheaded by the Judges Club, demanding the independence of the judiciary ahead of parliamentary and presidential elections.

After negotiations with the state, the judges agreed to oversee the elections with promises of a modified law to ensure the independence of the judiciary.

Seeing a continuation of rigging in the elections, the Judges Club released a blacklist of the judges that took part in the rigging and Bastawisi, along with fellow Judge Mahmoud Mekky, went public with statements, announcing that the elections were not clean and questioning the independence of the Supreme Judicial Council.

As a result, the two highly respected judges were referred to a disciplinary board, a decision that angered the judges and led to a sit-in at the Judges Club.

Both judges ended up acquitted of the charges they faced, but Bastawisi’s final episode with the state was apparently too much for his heart to take. One day before his hearing, he suffered a heart attack that reportedly led his heart to stop for four minutes.

Mahmoud Abul Leil, then justice minister, admitted before his death last year that signing the papers to refer both judges to a disciplinary board was the worst moment in his life, and that he did it because of state pressure coming from Mubarak himself, who insisted that the judges be punished for publicly criticizing the judiciary.

Following this ordeal with the state, Bastawisi accepted a mission in Kuwait in 2007, only returning to Egypt after the eruption of protests in 2011.

Running on a leftist party ticket

Brought up in a house with a mother from an Islamic background and a leftist father, Bastawisi says he grew up with a critical perspective on political ideologies that allowed him to take what he believes in from each without sticking to one ideology.

After returning to Egypt in 2011 and announcing his bid for presidency, Bastawisi suspended his campaign in November and returned to Kuwait. He says that seeing the confusion in the political scene and the possibility of postponing the elections, he couldn’t afford being on an unpaid leave for much longer with a family of four to support.

Bastawisi finally returned to Cairo in March this year to present his candidacy papers.

Unable to collect the 30,000 endorsements required to run for presidency due to a shortage of time and money, Bastawisi decided to run on the ticket of the leftist Tagammu Party.

However, he says the party gave him the freedom to differ from its ideology in his platform, making him the candidate of all Egyptians, not only the political left.

Hussein Abdel Razek, Tagammu Party secretary general, said the party picked Bastawisi because, in addition to his honorable past, they felt he would represent the party’s ideology because he had been a member of the party briefly after graduation, before his judicial post forced him to disengage from politics.

Abdel Razek said the party leaders assisted Bastawisi in forming his platform, but that they adjusted the party platform in order to suit a presidential candidate running for the general public and not on a leftist agenda.

Building a state of institutions

In his platform, Bastawisi calls for a country of institutions and decentralized government, fighting the ultimate powers given to the president under the constitution. He says that his vision would lead to a mix of parliamentary and presidential systems, which would resemble the French government arrangement.

Bastawisi suggests a presidential council to be elected in place of a president with vice presidents for different specializations. He also suggests a board of assistants to the presidential council, consisting of members under 40 years old to give the new generation the political experience necessary to lead the country in the future.

He suggests a decentralized system in which every governorate has an elected local council that acts as a local legislature and decides on the use of the budget allocated for that governorate. He also calls for the rebuilding and reform of all state institutions and the development of a job description for all state employees to avoid abuse of power.

Bastawisi suggested a controversial constitutional principles bill last June that gives the military immunity against civilian oversight over its budget, an issue that has been a source of contention throughout the military-ruled transition.

According to the bill, a national security council would be the only body allowed to discuss the military budget and would only include the president, the head of the armed forces and the head of the military intelligence, among others. MPs and ministers could be included in some sessions if invited by the core members of the council, but they would have no power to vote on the council’s decisions. The council would also be shielded from media attention, and the decided budget would not be disclosed to the media until 30 years after the date of its release, per Bastawisi’s proposal.

Bastawisy said in television appearances that while he roots for a safe exit for the military from the political scene, this doesn’t mean giving the military rulers immunity against prosecution for crimes that investigations prove they have committed during their time as rulers.

Betting on low chances

Barred from politics by profession, Bastawisi is criticized as a presidential candidate for his lack of experience outside of the judicial sphere.

And he sometimes seems out of place in politics. He shuns propaganda techniques traditionally used by politicians, and has not departed from his characteristic reverence and calmness that his judicial role taught him over the years. This has made his mission of reaching the majority of Egyptians, most of whom are not familiar with his history in the judiciary, a difficult task.

Bastawisi has also refused financing from businessmen to his campaign, relying on the limited capabilities of the Tagammu Party. The party itself, an incumbent opposition entity, has been marred with internal disputes and has not claimed a prominent position on the outbreak of the 25 January revolution.

He is competing against a field of three main left-leaning candidates, none of whom are seen to have much of a chance in winning the overall election: Nasserite journalist Hamdeen Sabbahi, labor lawyer Khaled Ali and Socialist Popular Alliance Party candidate Abul Ezz al-Hariry.

And it’s not even for sure that Bastawisi will be able to squeeze in the race for the left, many observers don’t see the liberal constituency as large enough to absorb four different candidates.