The public beach in Shalateen was largely deserted, except for a few local Bedouin men, women and children lying on the sand, lazily strolling in the ankle-deep waters of the low tide, or listening to Gulfi music while preparing Bedouin-style coffee, known as jabana. Around 1000km from rowdy Cairo and its infamous air pollution and traffic jams, the trip to the seaside was a welcome change of scenery. The breeze carried bits of the children’s conversation to where we sat. We had chosen a spot away from other people in order to give them their space. They were wondering whether or not we were foreigners, and it was clear that seeing strangers in this town of 3000 was a relatively rare sight.

The beach of Shalateen stretches across one side of the town, with only a small marina in sight. Encouraged by the women walking along the far end of the shore, we ditched our shoes, rolled up our pants and sauntered across the 500 meters of shallow water to where we could easily observe some aquatic life. Shortly after walking along patches of sand and seagrass trying to avoid being bitten by small fish or stepping on tentacles coming out of the sand, we were back on shore.

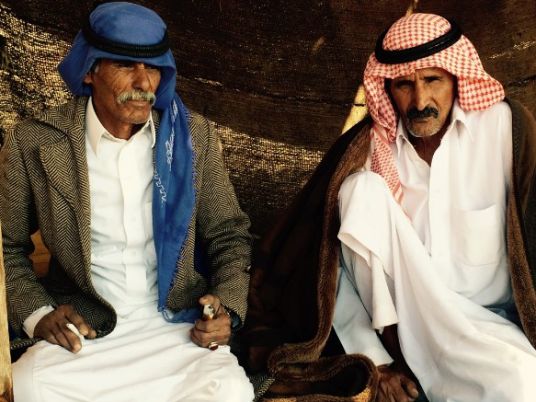

Stripped to the waist after a dip in the warm waters, one of the children around shouted "hello". We responded in Arabic and were immediately recognized as Egyptians. Moments later, the same boy approached us demurely and asked if we would like to join the men huddled under their makeshift tent nearby. The four men, seemingly in their early 20s, were sitting leisurely around a small fire sipping jabana and smoking shisha. A large piece of white cloth held between their pickup truck and two wooden stakes provided shade. The voice of Saudi singer Mohammed Abdou cut through their quiet chatter and they seemed friendly. We instantly accepted the offer of coffee since it was a good opportunity to mingle with the locals away from the watchful eyes of plain-clothed police informants in the more crowded part of town.

The conversation started with formalities. The men welcomed us, asked where we were from and what brought us to Shalateen, in friendly but reserved tones. They were not aware that we were writers, and questions regarding our occupation came much later.

These men were first generation town dwellers. Their parents came from the mountains but they had been born in Shalateen, in the words of one of them, "back when Shalateen was [the size of] a kiosk." A casual conversation that started with their accounts of life in Shalateen soon turned into what seemed to be everyone’s favorite topic: marriage and dating. What is the best way to find a wife? What to look for? How do you get a girl to talk to you? One inquisitive question followed another as they started to open up.

In the beginning, shy as they were, they asked if it was okay to talk about marriage in the presence of a woman. "If we talk about girls in front of other girls here [in Shalateen]," one of them said, "they quickly walk away from the conversation. They are really shy."

This invited a comparison between Cairo women, who were seen, positively, as more open and forward, and Shalateen and mountain women who are much more shy and reserved. They said that Shalateen’s women rarely go out of the house, even to the markets, which was something we had already observed. It’s the men who do the household shopping there, they explained, since it is seen as "inappropriate" for women to mix with men in markets.

However, they told us, laughing, that since watching satellite channels and soap operas the younger generation of Shalateen brides have become more demanding. "Now they want a television and a washing machine, and they want to be taken out to the market or the seaside," said one young man. "It’s becoming more difficult."

The young men also wavered between wanting to know how to get women from outside the tribe and a conviction that they will marry their cousins. But like their land, they seemed to be unspoiled, with a child-like innocence in their questions and their amazement at the small discoveries they were making.

We were told that it is difficult to marry outside the tribe. While the Ababda tribe, to which this group of men belong, and the Bishariyya or Beja tribes do mix occasionally, it is rare. The family prefers a close relative so they can be sure the man will care for their daughter. The family has less control over someone from outside the tribe. The dowry, they told us, ranges from LE1000 to LE3000, depending on how close you are to the bride’s family. It is paid in camels. Wedding gifts can be jewelery, a sword or a giraffe-skin whip. "The important thing is that you are a good man, you pray and fast, and if so they just ask you for what you can afford," one of the men said.

"Young men here talk a lot. They say they want to marry from outside and that they want to move away, but in the end they do nothing," concluded the youngest among them. This summed up the group’s attitude. While they looked at the outside world in amazement and wonder, and while they talked about adopting new lifestyles, in the end they were clearly loyal to their customs and they stuck to what they knew. It seemed that breaking with tradition and leaving behind their accustomed lifestyles is a risk few are willing to take.

But soon the tables were turned, and we were on the receiving end of the questions. "So if I go to Cairo and see a girl I like on the street, how do I marry her?" one man asked us. We tried to explain that in the capital marriage is far more complicated than that, but it was unclear if we got our point across.

One of them soon told us an anecdote that betrayed his sensibilities when it came to women:

"I once tried to get a girl’s attention while she was walking in the street, I shouted ‘Honey!’ at her," he said, and the giggling soon followed from the group as they remembered the incident. "She then told us, look in front of you, you monkeys." More giggling followed. He seemed to be convinced that the remark was deserved because they look "ugly", and they were not the first tribe members to hint at that, despite their pleasant features and air of refinement.

We explained how catcalling, or trying to get women’s attention that way on the streets amounts to harassment. One of them then replied in genuine bewilderment, "but ‘Honey’ is a nice word, why would she be upset from hearing a nice word?"