It was 10:56 pm at mission control in Houston on July 20, 1969 when Neil Armstrong became the first person to step onto the Moon.

AFP dispatched several journalists to cover the exploit, which was broadcast live from the Moon’s Sea of Tranquility to NASA’s Johnson Space Center and on to televisions around the world.

This is their summary from that day 50 years ago, translated from the original French. The quotes have been crosschecked against the NASA transcript.

The conquest of the Moon

SEA OF TRANQUILITY, July 20, 1969 (AFP) – On Sunday at 10:56 pm US time (0256 GMT), Armstrong — after seemingly never-ending suspense — steps on the Moon.

A few hours earlier the mission commander had suddenly announced to the world that he would exit the lunar module five hours earlier than planned.

The descent for man’s first steps on the Moon gets under way.

– 7:42 pm: The astronauts start preparations for the excursion. They put on double-visor helmets, boots, reinforced gloves and backpack-like life support gear, also checking that the pressure, radio communication and oxygen systems are working.

– 7:50 pm: NASA announces the preparations will take two hours. Armstrong will not exit before 10:00 pm.

– 9:55 pm: They depressurize the spacecraft, at the same time pressurizing their spacesuits.

– 10:00 pm: The lunar module empties.

– 10:15 pm: Their spacesuits are fully pressurized.

– 10:20 pm: Everything is going smoothly. The lunar module remains depressurized. The astronauts now rely entirely on their life support systems.

‘Giant leap’

– 10:56 pm. Armstrong puts his left foot on the surface of the Moon and declares: “That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.”

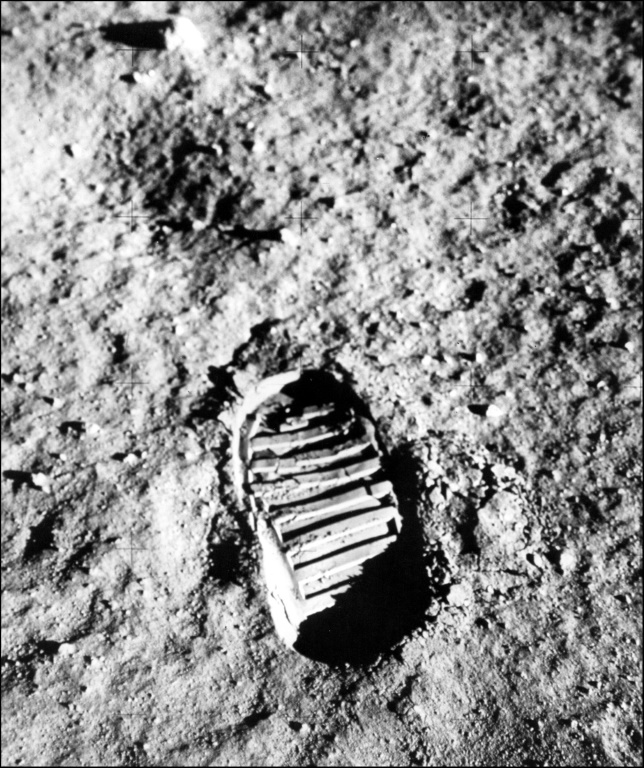

Before fully putting his foot down, the commander had carefully felt out the surface with his boot to check its solidity.

“I only go in a small fraction of an inch, maybe an eighth of an inch, but I can see the footprints of my boots and the treads in the fine, sandy particles,” he says, surprised, taking his first steps.

“There seems to be no difficulty in moving around — as we suspected. It’s even perhaps easier than the simulations… .”

He moves with seeming ease, millions of people back on Earth watching and listening as the images are beamed back live onto televisions in homes around the world.

They have seen the conqueror of the Moon come down the nine struts of the ladder leaving the module, test out the surface, let go of the handrail, take his first steps and collect the first samples of lunar soil.

Armstrong uses a bag on a telescopic stick that he takes from a pocket to scoop up the soil. He then seals the bag and tosses the stick — the first of several items of Earth litter to be left behind when the astronauts leave.

He pushes the bag into his thigh pocket, feeling blindly and guided by his teammate Edwin Aldrin who is watching over him from the height of the module’s hatch.

American flag

It is now 11:15 pm. Armstrong has already spent 19 minutes alone on the Moon, 19 minutes during which, in the indefinable solitude of the dead planet, he has demonstrated perfect composure.

At that moment Aldrin makes a bounding appearance. Reassured by Armstrong’s experience, he boldly jumps off the ladder, also putting down his left foot first.

The two men, in an act of patriotism, plant the US flag into the Moon. They then read aloud from a plaque, fixed to the spacecraft’s front landing gear, that is inscribed: “Here Men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon, July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.”

Having accomplished this symbolic gesture, they go on to move a camera that is fixed to the module and streaming images of the white surface of the Moon, its horizon slanted on a very black background.

Armstrong first hangs it around his neck: on the small screens back on Earth, the image dances around.

The mission commander then takes a few steps and fixes the camera on a tripod.

It sends back a panoramic view: the lunar module against a background of countless miniscule craters with oversized shadows and, far off, the horizon, a clearly curved line demarcating the Moon’s surface, glittering under the Sun’s light, and the black abyss of the universe.

The image becomes clearer. One can make out the footprints of the astronauts on the grey-white surface, the firmly planted star-spangled banner.

The two men advance with surprising lightness, as if dancing. A strange ballet is taking place on the Moon. Their heavy spacesuits — fireproofed armour with reinforced joints and weighed down by the survival backpacks — seem no bother.

Nixon on the line

11:49 pm: Ground control announces that Richard Nixon is on the line. He is going to talk to the astronauts, as planned.

Immediately the screen divides. On the left is the US president reading, from the White House, a message over the telephone. On the right are Armstrong and Aldrin, motionless, listening to the voice coming from Earth, 380,000 kilometers (236,000 miles) away.

“For every American, this has to be the proudest day of our lives,” he says. “Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world.”

“Thank you, Mr President,” replies Armstrong. “It’s a great honor and privilege for us to be here.”

They resume their tasks, Aldrin unfolding a “solar wind collector” that consists of a thin aluminium foil sheet that opens up like a blind. It will gather particles of the various gases that make up the wind — helium, argon, neon, krypton, xenon — for analysis back on Earth.

Bouncing around in all directions in “kangaroo hops”, the astronauts have already spent more than an hour on the Moon. Their doctor Charles Berry, who has been watching their every movement from Houston, says they are in “perfect shape”.

They collect samples at random, putting them into plastic bags to be stored later in sealed metallic containers.

As they work, the astronauts make use of a range of tools that they pull out from the module’s trunk-like Modularized Equipment Stowage Assembly: pliers, pincers, shovels, picks, a hammer, sample tubes and scales.

These instruments are larger than those that would be used on Earth since the astronauts’ chunky reinforced gloves prevent them from handling small objects.

And as their spacesuits mean they cannot bend down, the instruments all come with long, telescopic handles.

Dead star?

At 00:15 am the collection of samples is over, the astronauts having gathered 27-28 kilogrammes (about 60 pounds) of Moon stones and rock.

The first mission accomplished, they now have to set up two instruments that will be left on the Moon: a seismograph and a laser reflector.

The most delicate is the sensitive seismograph, the most accurate ever built. It will record the slightest tremors to rattle the Moon and determine whether they are caused by the impact of meteorites that constantly bomb its surface or are of volcanic origin, like earthquakes.

Meant to function for a year, its installation is the astronaut’s main objective as its data should show whether the Moon is a dead star or not.

The laser reflector is made up of 100 prismatic mirrors composed of quartz crystals and intended to reflect the beams of rays reaching the Moon from various points of the Earth.

Set up in four minutes and intended to function for around 10 years, it will enable calculations to within a few centimeters (inches) of the distance between the Earth and Moon, which is now only known in meters (feet), as well as the exact shape of the Moon, its dimensions and oscillations on its core.

The reflector will also help to determine the speed at which the Moon is moving away from the Earth and collect information about the Earth itself.

This includes the exact distance between the continents; if they are drifting from each other; activity on the geographic North Pole; the speed of its rotation and oscillations on its axis.

The two instruments are in place. Working non-stop, the astronauts all the time continued to pass on to the Houston control center their impressions and observations.

Armstrong signals that he has spotted, around the module, endless small craters, which he compares to holes caused by a BB shot pellet gun.

Moon curse?

The mission comes to an end. The astronauts pack up, leaving on the Moon the 11,000-dollar camera which had so faithfully recorded their movements and transmitted them back to Earth, as well as the tools they used.

Their samples are hoisted back into the lunar module on a clothesline-like wire on a pulley inside the spacecraft. They fold up the “solar wind collector” and send it up along the wire.

Aldrin takes the ladder’s nine rungs back up into the module and grabs the items passed up by Armstrong, carefully stowing them inside.

Armstrong has now been outside for more than two hours and 10 minutes, Aldrin about 20 minutes less.

The operation has been without incident except for when Aldrin dropped a film pack. Armstrong picked it up immediately, easily, almost nonchalantly, showing again that all NASA’s worries about the difficulties the astronauts could face moving on Moon were unwarranted.

The incident also allowed Earth to hear the first lunar curse. Aldrin, furious at his own clumsiness, lets slips a resounding, “Damn.”

Aldrin enters the module. Armstrong takes a last look around, grabs the handrails of the ladder, climbs up, enters the craft and closes the hatch. It is 1:11 am Houston time. The first exploration of the Moon is over. A total success.

Just five minutes before they go back up the ladder, NASA had let the men know that the laser reflector was already functioning perfectly. A laser beam sent from California had already reached it and been reflected back.

‘Hallelujah’

All that remains for the two brave space explorers is to clean up. They sweep towards the hatch the film-less camera used to photograph their Moon rock collection, their boots, gloves and survival packs, as well as empty food bags and full urine ones.

Having depressurized the cabin again, they open the hatch and shove the pile out onto the Moon. The module is closed and repressurized a last time, allowing the men to eat and sleep.

About 12 hours later, at 1:55 pm, they must takeoff from the Moon to return to the mothership. There command pilot Michael Collins awaits, one of the few Americans not to have seen the two spacemen in action live on television, although he was able to follow via radio.

Watching over them from above, when Collins learned that the expedition had concluded in triumph and his teammates were safe and sound aboard their module, he expressed his joy and relief with a single word: “Hallelujah!”

afp-ber-eab-br/jmy/ia

Image: NASA/AFP/File / – Footprint on the Moon from one of the Apollo 11 astronauts