At each other’s throats for two decades, militants of Venezuela’s socialist state and opposition seldom agree on anything. Yet mention the name of presidential candidate Henri Falcon, and both are liable to spit.

“Traitor!” cry socialist stalwarts, who cannot forgive the former state governor for breaking with their beloved late leader Hugo Chavez in 2010.

“Chavista lite!” say opposition radicals, always suspicious that Falcon came into their ranks as a Trojan horse.

Now that the 56-year-old former soldier is running for president in a May 20 vote, both groups are united in scoffing at his chances.

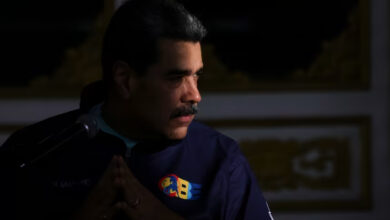

After all, Falcon is up against not just a powerful President Nicolas Maduro but also an election system widely considered unfair and an opposition boycott that will deprive him of votes.

And yet, a clutch of opinion polls show Falcon ahead, bolstering his campaign mantra that he is a natural transition candidate with appeal to a moderate majority fed up with political polarization and economic chaos.

Widely-followed pollster Datanalisis, for example, put him more than 10 percentage points ahead in voter intentions.

“This government is finished,” Falcon told Reuters, noting how few governments in history had survived hyper-inflation and economic chaos like Venezuela’s current crisis.

Opinion surveys in Venezuela are often divergent, politicized and misleading in hindsight. But Falcon, his campaign team and some pundits think he may be able to create an avalanche as the campaign gets underway.

“If we really unite, get organized, construct a single narrative, and instead of discouraging people by asking them to abstain, we call them to vote, there’s no way this government can beat us,” said Falcon.

MADURO’S ADVANTAGES

Despite such optimism and Maduro’s unpopularity on the streets, there appear to be plenty of ways for the government to assure victory.

It is ratcheting up welfare handouts and pressure on state workers, has skilfully fomented divisions within the opposition, barred Maduro’s two main rivals from standing, brazenly uses state resources in its campaigns, and benefits from a compliant election board.

The board’s head, Tibisay Lucena, is on US, EU and Canadian sanctions lists accused of violating democracy. Even its chosen vote machine operator, UK-based Smartmatic, accused her institution of fraud in a vote last year.

“Though Falcon is twice as popular as Maduro and could beat him in a competitive race, the 20 May vote will not be competitive,” wrote Eurasia consultancy.

In line with his promise of a government of “national unity”, Falcon is reaching out to opposition leaders like former presidential candidate Henrique Capriles to relax the boycott and join his campaign.

He has picked a Wall Street bank analyst, Francisco Rodriguez, to head his economic team.

And in a nod to his former allies in the ruling “Chavismo” movement and a signal to the armed forces that they need not fear him, Falcon may keep Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino should he win, a campaign aide said.

But to win, Falcon needs to convince voters in places like La Vega, a poor hillside ‘barrio’ of Caracas that is a traditional ‘Chavista’ stronghold.

At a bread shop there, chatter revolved around impossibly high food prices and the growing migration of Venezuelans to Colombia. There was next to no enthusiasm either for Falcon or Maduro.

“I want to vote to change this disaster! But there are no good candidates,” said Jose Sanchez, 25, an internet cafe worker whose minimum monthly wage – less than $2 at the black market rate – does not even cover diapers for his twin babies.

“Let’s see if Falcon has changed since his Chavista days. I suppose I might vote for him, but only to get rid of Maduro,” added Sanchez, who voted for the opposition in recent polls.

‘HUNGER PUMMELING US’

Driver Gustavo Isturiz, 56, said he voted for the government in multiple polls since Chavez won office in 1998 but was fed up with rising penury.

“Hunger is pummeling our stomachs, but the opposition still has no chance,” he said. “I can’t go over to them until a good candidate appears. I don’t like Henri Falcon: he has no political project and he’s not inspiring hope.”

Some in La Vega’s winding streets said they were so reliant on state handouts they would not dare to vote against Maduro for fear officials would see their ballot and cancel their benefits.

Falcon, whose energy is evident in his daily pre-dawn jogs, plans to start street campaigning in the next few days. He vows to keep popular welfare benefits but also open Venezuela’s economy along more business-friendly lines.

His adviser Rodriguez recommends dollarizing the economy, seeking $15-20 billion in annual foreign funding, lowering taxes for oil investors, and dismantling currency controls.

Falcon faces a tough job persuading western nations to withdraw their objections to the May 20 vote.

The United States has been vociferous, threatening to extend sanctions on the Maduro government to hit the oil sector if it goes ahead with what critics are calling a “coronation” on May 20.

Its top diplomat in Venezuela, Todd Robinson, met with Falcon recently, sources close to the candidate said, trying to persuade him to withdraw as his challenge was undermining U.S. efforts to isolate Maduro.

Washington seems to be calculating that if Maduro scores a Pyrrhic victory, and is left governing a ravaged economy, military and social pressure will become unbearable.

“If Maduro wins, as looks likely, it will be a very unstable government,” said Caracas-based consultant Dimitris Pantoulas. “At home, he is flirting with a coup d’etat and abroad he will be a pariah.”