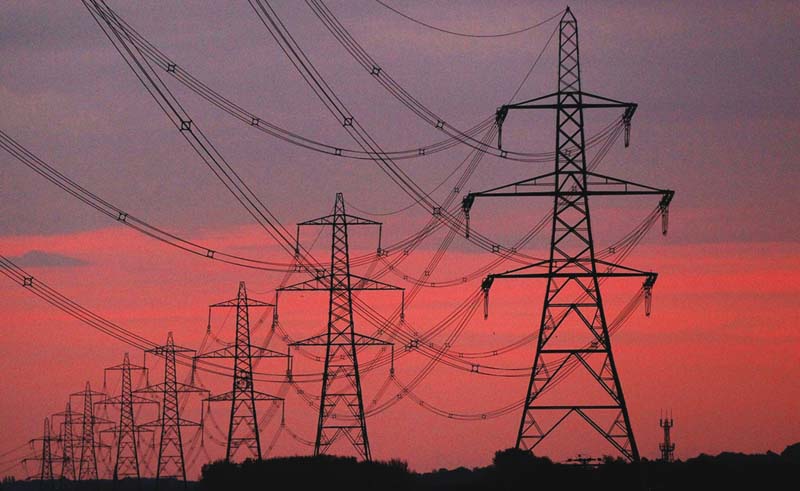

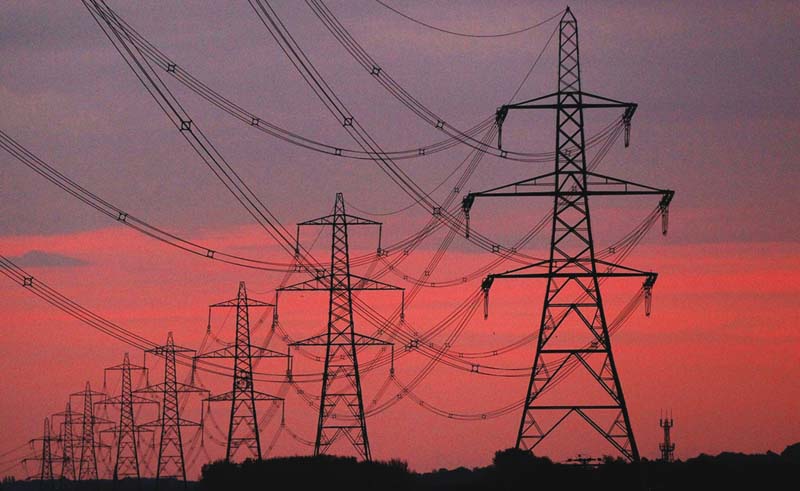

When the streets of Ezbet el-Haggana are flooded with rain water in the wintertime and children go out to play in the rain, they often hear a loud sputter—which they have dubbed the "voltage vampire."

Residents of el-Haganna know well that they have to keep their vampire happy. Provoking the wrath of the vampire might just burn down the entire area. Almost every home in el-Haggana has had a fire break out or a member of its family die at some point because of the high-voltage networks.

Fathi is a six-year-old victim of these heartless high-voltage networks. One day, his parents left him sleeping and went out. It never occurred to them that anything could go wrong. But it did. A small piece of cable from the high-voltage network landed on the roof of their wooden house, the house instantly caught fire and the startled boy, seeing both his legs on fire, jumped out of the window.

Yet with all the burns he suffered, Fathi is by far luckier than many other children who have lost their lives to the voltage networks.

Eight-year-old Mohamed was playing on the roof of his house with a sugar cane stick in his hand–totally oblivious to the danger posed by the electricity networks–when the stick accidentally touched a high-voltage cable. Only a week later, little Mohamed died, no longer able to withstand the intense pain of his burns.

Although years have rolled by since the sad incident that took Mohamed’s life, Mohamed’s mother still recalls all the gruesome details and fears going up to the roof. "Nobody ever thought of compensating us for the incidents. Maintaining a high voltage is all the government cares about," she laments.

Ignorance on the part of the residents of Haggana may be responsible, to an extent, for these incidents–for example it was expected that hooking up a cable to the high-voltage network would light up the home and make life happier, when, in fact, it did quite the reverse.

Ashraf Mohamed lost his father, brother and cousin all in the blink of an eye when an iron rod that his father held in his hand came into contact with a high-voltage cable and the three were cruelly charred to death.

Although residents are now better aware of the dangers of coming into contact with the deadly cables, most of them don’t recognize that their proximity to the networks could be causing them to develop diseases as well. In any case, though, they have nowhere else to go.

Many of the children here are affected by a disturbance to the flow of electricity in their brains. Hashem is a four-year-old boy who suffers from recurrent epileptic fits, but his mother cannot afford a home elsewhere.

In one of the homes lying right under the high-voltage networks lives Wagiha Fattouh, 45, who told us the story of her 21-year-old daughter Heba. Heba complained of a chronic headache and occasionally suffered from what seemed like epileptic fits. Doctors said she had a benign brain tumor, and she had an operation to remove the tumor despite warnings that she might suffer serious complications following the operation.

Dr. Sherif Darwish, a neurologist, warns of the serious health problems residents in high-voltage areas could suffer, which range from migraine and lowered immunity to disturbed electrical flow in the brain and tumors. Those most vulnerable are pregnant women, children and old people. High-voltage areas also tend to have a higher incidence of autism and Down’s syndrome.

Abdo Abu el-Ela, a manager at the Shehab Institute in Haggana, says that the presence of the high-voltage networks has deprived the area of basic infrastructure. The area has only one medical center that opens for just three hours a day. And sanitary drainage networks were introduced by civil society organizations, not the government. Abu el-Ela believes the government doesn’t acknowledge the existence of Haggana’s population.

Several solutions to the problem were proposed more than five years ago, Abu el-Ela adds. It was suggested that the network be diverted away from the residential block, buried underground, or insulated–all these ideas being rejected due to a lack of funds. There were also suggestions regarding providing alternative housing for residents in an area away from the networks, but even that suggestion was rejected, according to Abu el-Ela.

Sayed el-Bazz, one of the residents of Haggana, says the networks will not be relocated to protect the residents’ health, but because the officials at Cairo Airport complain that the networks are interfering with flying equipment.

Meanwhile, residents of Ezbet el-Haggana are learning to cope and prefer to believe the promises made by members of the People’s Assembly, who say that the networks will eventually be relocated outside Haggana.

Translated from the Arabic Editon.