The day before polls open for Libya’s first National General Congress elections, reports have warned of potential violence in the country’s eastern region, following a recent attack on the Benghazi elections commission.

Egypt’s Foreign Ministry has cautioned against ground travel across Libya and election monitoring groups, including the Carter Center, have launched limited missions, avoiding potentially volatile areas such as Benghazi.

In Tripoli, however, calm reigns, save for the sporadic outbursts of gunfire at night and gun-brandishing rebels at checkpoints along the coastal road. At night, a procession of trucks carrying aircraft missiles passes nonchalant bystanders on a crowded street, as the distinctive crack of Kalashnikovs sounds in the distance.

Many are anxious here, but not due to the threat of violence. After months of political unrest under the interim government of the National Transitional Council (NTC), the residents of Tripoli want a return to stability and normalcy.

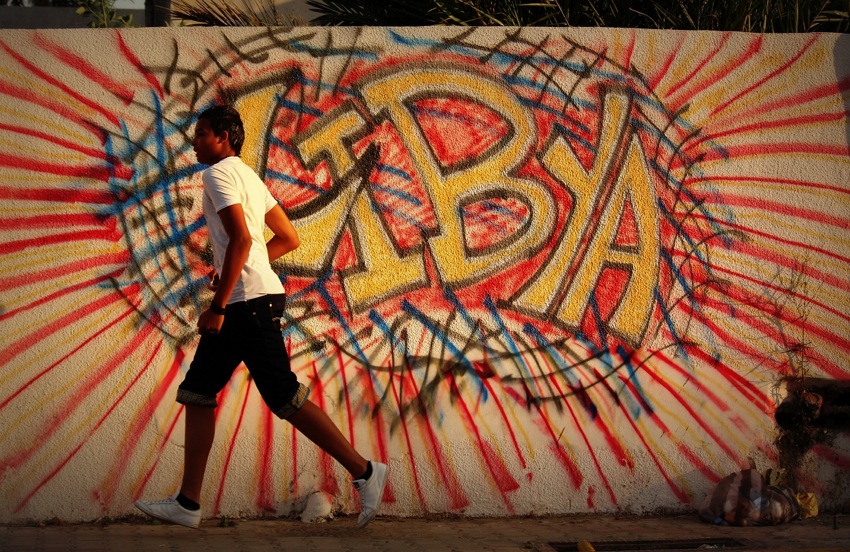

On the outskirts of Tripoli, the demolished compound of Bab al-Aziziya — one of Qadhafi’s many strongholds across Libya — is a daily reminder to commuters of the carnage the city and its people have suffered. Shrapnel is firmly lodged in the walls of countless homes and mosques across the city, and each street corner carries the photos and graffiti of the neighborhood’s dead heroes.

The memory of war is still rife here, which is possibly why the tough-skinned city residents downplay the threat of violence and the repeated armed disputes breaking out across the country. To them, the occasional battles are the settling of scores between tribes, as well as revolutionaries and Qadhafi supporters. A lot of blood has been shed, and a lot of bad blood remains. It’s a tense environment for elections.

Billboards and walls everywhere are plastered with candidates’ faces and the National Transitional Council’s campaign to encourage voter turnout. Slogans call for unity, reconstruction, prosperity and democracy, but many locals are either confused about the nature of the elections or voting based on their preference for a personality, rather than a political program.

A total of 3,707 candidates are vying for seats in the National General Congress; 1,206 candidates are running as part of the 142 registered political parties, while 2,501 are running as independents. The candidates are vying for 200 seats in the congress, which initially was to select an assembly that would write the constitution. However, on Thursday, the NTC passed a new law stating that the assembly members would be elected by the public at large, not appointed by congress, thereby stripping the congress of one of its core functions and rendering the congressional elections less important just 48 hours before polls opened. A referendum will be held on the constitution, and then parliamentary and presidential elections should follow.

Farid is a driver from the suburb of Hay al-Akwakh and one of the 2.7 million Libyans registered to vote. Twenty-four hours before the elections, he still doesn’t know if he’ll vote, and if so, for whom. “There are just too many names,” he explains. “I don’t even know what their plans or their personalities are.”

His confusion isn’t helped by the complicated electoral system: 40 members will be elected by plurality vote in single member constituencies, while 80 members are elected by plurality vote in multimember constituencies, and 80 members are elected through a closed list proportional representation system.

In Souq al-Turk, a bustling marketplace surrounding the Old City’s Turkish fortifications, Ahmed and Faisal share a galabeya kiosk yet nothing in politics. Ahmed is from Benghazi, and plans to boycott the elections due to what he sees as an unfair distribution of seats — the seats have been divided according to regions, with 106 of the 200 seats going to the western region, known as Tripolitania, while 60 seats go to the eastern region of Cyrenaica, which includes Benghazi, and just 34 to the southern region.

While the NTC has attributed the distribution to the demographics of the country — Tripolitania has the largest populations — many in the East have strongly criticized what they see as a continuing centralization of power in Tripoli. They see the East as the birthplace and stronghold of rebellion and believe that it ought to be credited, therefore, with equal political power.

Ahmed, like many from Benghazi, has heeded the call of the Cyrenaica National Council, a group formed in March 2012 that calls for eastern autonomy and a general boycott of elections.

Faisal is from Tripoli. Like many in the city, he says he will vote for Mahmoud Jibril, leader of the National Forces Alliance. Jibril is a popular figure who served as interim prime minister for seven months during the revolution, but his former position as head of the National Economic Development Council in 2007 has led other Libyans, such as Ahmed, to denounce him as a remnant of Qadhafi's regime.

“If you joined the revolution in its late stages, you’re more than welcome to join, but you should take a backseat afterwards,” says Ahmed. “Your reputation has been sullied as one of his sympathizers; so you should not be involved in politics.”

Qadhafi is rarely referred to by name here; instead some merely say “he” while others call him “Al Mardoum,” the fallen.

“Before the revolution we were afraid to mention his name,” says Soheil. “And during the revolution we called him all the names under the sun. Now we don’t mention him because we don’t want to glorify his memory.”

Soheil is from Benghazi, while his fiancée Sarah is from Tripoli and of Amazigh (or Berber) ethnicity. The Amazigh were the original nomadic inhabitants of Libya, yet they were banned from forming a political party based on their long-suppressed identity when the NTC passed a law in April 2012 banning parties based on ethnic, tribal and religious foundations. Widespread outcry forced the NTC to amend the law to allow religious political parties, but ethnicities and different tribes were prevented from political representation.

Soheil’s friends Bashar and Habib fought as rebels in the East during the uprising. Now disbanded and back at their desk jobs, they regard the elections with chagrin and indignation. To them, none of the candidates represent their toil as freedom fighters, or do justice to the horrendous loss of life and destruction suffered by the Libyan people.

“You have four types of voters,” says Soheil. “Those who will vote for persons, not parties, those who will boycott, those who don’t know who to vote for, and those who will prevent everyone from voting.”

Bashar and Habib agree that the threat of targeted electoral violence in the East is real.

According to Bashar, there are eastern militias who have already expressed their intent to disrupt the elections and prevent others from voting due to their belief that the elections are illegitimate and based on political negotiations.

“The Derna militia wrote on a wall outside a polling station that elections equal explosions,” Soheil explains. “That’s a threat that should not be taken lightly. When the people of Derna speak, we all stay silent.”

Derna is a stronghold for Islamist jihadi fighters. They have lost hundreds of men in battle across the country and are considered by Bashar and his friends to be the hardcore fighters — a force to be reckoned with and a threat that should be taken seriously.

Soheil will void his vote, but he predicts that the Muslim Brotherhood will win. “Here, our only option is the Muslim Brotherhood,” he says. “Either they are the leaders of the party, or they are members in all the parties. We can’t avoid them.”

The Muslim Brotherhood’s strength is evident in the number of leading political parties either founded by former clerics or members of the Muslim Brotherhood. While some political parties, including Jibril’s, are identified as nationalist, all political parties seek to uphold Sharia and conservative Muslim values. There is no question of a secular state here in Libya.

It’s tempting to draw parallels between Libya’s political parties and Egypt. The Muslim Brotherhood dominated Justice and Development Party faces off against the National Forces Alliance, a party headed by a member of the former regime, albeit one with real revolutionary credentials. But, in fact, the differences are acute.

Libya’s fragmented society has produced complex political groupings. Many of the tensions troubling the country are complicated by tribalism, a factor that Qadhafi exacerbated by favoring certain tribes and discriminating against others. And while a Salafi community does exist in Libya, Soheil and his friends downplay their threat.

“In Egypt, the Salafis are aggressive, here they stay at home and we ignore them,” he explains. Early in the revolution, Salafi figures denounced the uprising against Qadhafi as haram, or forbidden. Today, they seem to have little street support in the run up to the elections.

While there appears to be little campaigning by the candidates and coalitions save for the billboards and posters everywhere, the elections are certainly a momentous turn of events in recent Libyan history. Still, most of the locals interviewed by Egypt Independent voiced their support for individuals based on their personalities, rather than coalitions based on their politics.

In fact, several people assumed the elections are for the presidency, not for congress, and expressed their hope for a new leader. While Qadhafi’s absence is certainly not missed in this city, he has left a void that many are anxious to fill with a new leader.

“Ultimately, it doesn’t matter who wins the elections,” says Soheil. “It’s what happens afterward that counts.”