At the St. Cyril Melchite church in Heliopolis, several generations of Egyptians of Levantine descent came together to hear about a new book chronicling the history of families like theirs.

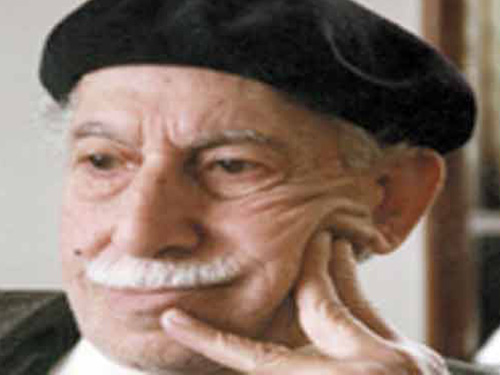

Hijrat al-Shawam (Levantine Migration) by Lebanese historian Massoud Daher focuses on the trajectory of Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian families who have migrated to Egypt since the mid-1700s. It is a recent release from the Egyptian publishing house al-Shorouk.

Daher conducted archival research to trace Levantine migration and the result is an account that depicts stories through various types of documents. Daher’s work has been deemed “scientific” and methodical because of its use of documentary material to create a social history. Hirjat al-Shawam brings to mind past works about Levantine migration, notably Robert Sole’s novel Birds of Passage. But unlike Sole, Daher refrains from romanticizing the stories’ of migrants.

Daher’s archival research focused on the registries of various churches that housed Levantine Christians, such as the Armenian Catholic church, the Maronite church, the Greek Orthodox church, and the Melchite church. The focus on the church’s archives points to the central role that the religious institutions played in the Levantine diasporas, but Daher also explored other sources to locate traces of those communities’ lives in Egypt. Letters, memoirs, and university registration documents provided Daher with a glimpse into how these communities lived. His research also took him to published memoirs and newspapers’ advertisement about Levantine artists and intellectuals and documents of Levantine student unions.

Daher used the archives systematically and in his book they become central to telling the histories of Levantine communities in Egypt. The author stopped at each archival depository, dissected its content, and suggested possible readings into the lives of Levantine communities in light of this content. For example, in the archives of a Greek Orthodox church in Cairo, Daher looked at the marriage registries and used the information he found to identify trends of marriage within and outside the community. Daher read into the baptism and marriage registries of a Greek Catholic church in Port Said to understand the breadth of Levantine communities outside of Cairo. He went to the head of the Lebanese Students Association in Egypt who shared documents that showed how present and past-days Lebanese, Syrian, and Iraqi notables and state officials studied in Egypt.

This archive-based third of the book both contains information about Levantine communities in Egypt and at the same time showcases ways of using archival material to understand history. The work reminds readers of the power of archives to construct an image and shape a historic account. This information, however, could have been better integrated into a documentary or argument-based account of the lives of Levantine communities in Egypt, thus making for a more interesting read.

In another section of the book, Daher switches to memory as a way to look at history. This section compares memory and archival documents as sources of history. In doing so, Daher puts forth questions about veracity, details, the significance of information, as well as others. Daher interviews Levantine migrant families and presents their stories. The only classification Daher uses in this section is the family name. For example, in a section about the Kanaan family, which originated in the Mount Lebanon area, Daher interviewed Naguib Kanaan to learn about his family’s migration to Egypt. Through Kanaan’s account, the reader is exposed to a family genealogy that brings to light the fact that Youssef Kanaan, the great grandfather, was a prominent merchant in Cairo who financially supported the Egyptian king Muhammad Ali in his fight against his Mamluk predecessors. Although the Kanaan family’s migration to Egypt stopped and started across generations. Said Kanaan, the great grandson of Youssef Kanaan, studied medicine in Beirut and Istanbul, where he graduated from a military medical school that sent him to service in Cairo. The story continues, chronicling the lives of Said Kanaan’s offspring, while telling the history of a nation on the margins, with some intimate details about the relationship between Ottoman colonies, the balance of power during Muhammad Ali’s rule within the Ottoman context, and the breadth of the latter’s attempts to form a "modern state."

This section could not be described as anything other than a series of family histories. Daher leaves a space for readers with different historical interests to read small slices about a much bigger picture. Daher, celebrated as the “scientific historian” during the book signing, can also be called an avid aggregator.

At the book signing event at St. Cyril Church, panelists made suggestions about the larger context of Daher’s work. Politician Mustafa el-Fiqi spoke about the openness of late 1800s and early 1900s Egypt as a main element in why migrant populations came here as they tried to escape stifling colonial regimes. Khaled Ziyada, Lebanon’s ambassador to Egypt, referred to Levantine migration to Egypt as an interesting facet of Christian north to south migration, which is an uncommon trajectory today. Patriarch Gregorios III of the Greek Melchite Catholic church spoke about the interesting landscape of Arab countries, a pillar of which was the openness of borders to migrants. For Gregorios, a lesson from this past could be the need to work towards an area of open borders between Arab countries "through which we can come and go and trade and develop."

But for the crowd of generations of Levantine descent who attended the book signing, the mere mention of the names of their families and friends was enough to create enthusiasm about Daher’s book. As Daher presented his work, family names were picked from among the audience and audience members told their part of the story in a gossiping fashion. In a sense, they showed how gossip could become another means of constructing a social history. But more importantly, they showed a sense of community, of collective memory, and of collective experience.