Franziska Kohler, Tages-Anzeiger, AC Immune, Zurich, Switzerland

There is a long story and a short story to be told about Andrea Pfeifer. The short story goes like this: The 60-year-old businesswoman forgets nothing. She remembers every instruction she has given – until it has been fulfilled. Forgetting and not forgetting are central to her work: Pfeifer and her company AC Immune are fighting against Alzheimer’s disease, the biotech company is searching for a cure for memory loss. By 2020 it wants to have an effective therapy against the disease ready for distribution.

To understand the long story, one has to travel to Lausanne on the banks of Lake Geneva in Switzerland. At this time of year, fog envelops the city, icy rain washes the last patches of snow off the streets. During the weekend, Pfeifer was in the sun high above the clouds in Crans Montana, the alpine ski resort not far from Lausanne where the Alpine Ski World Cup for Women was taking place. She loves skiing, says the scientist of German origin. “But I would never launch myself down a slope the way these athletes do.” Much too risky.

In fact, Pfeifer herself has taken high risks of her own. With her company she is active in an area of research that has been waiting for a breakthrough for many years. Pfeifer is sitting in a meeting room in the Innovation Park of the Federal Technical University of Lausanne (EPLF), one of the leading research institutions in Europe. More than 160 startup and spin-off companies born out of research at the university have their offices here, including AC Immune.

Pfeifer founded the company 15 years ago. Before that, she was vice president of Nestle, the global food and beverage conglomerate. She was head of research, in charge of hundreds of employees – one of the top people at the company. She led the discovery of LC1, a joghurt that is reputed to regulate digestion. It became a global success, not least because of clever marketing. As a result, she was in contact with the press more than 200 times within a single year in Germany alone, Pfeifer said later.

But she gave up the comfortable position at Nestle to found her own business. She wanted to return to her roots in medical research. Pfeifer has a doctorate in pharmacology and worked for many years on cancer research at the National Institutes of Health in the United States.

From joghurt to Alzheimer’s – a huge change. Alzheimer’s disease is scary. It is estimated that in Switzerland alone 150,000 people suffer from various forms of dementia, of which Alzheimer’s is the most common. Until 2040, this figure is likely to double to 300,000 because Swiss society is ageing rapidly.

For decades, the big pharmaceutical companies have been looking for drugs against the disease. Several of them have now given up. Recently, US-giant Pfizer announced that it is withdrawing from development of drugs against Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s. It wanted to concentrate on areas of research that promised better success and commercial prospects. Eli Lilly, another US pharmaceutical giant, announced in January that its latest tests with a drug against Alzheimer’s had ended in failure.

But AC Immune is continuing with its research. One of its drugs, on which the company is cooperating with Roche, the Swiss pharmaceutical multinational, is in the final stages of clinical testing. For these drugs to be effective, they need to be used much earlier than has been common practice until now, Pfeifer says. Ideally even before the disease manifests itself. Which is why the company is also working on methods for an early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. “This year, we want to test a new method for detecting harmful deposits in the brain,” Pfeifer says.

Pfeifer has a vision: In seven to ten years it should be possible to predict whether a 40-year-old is likely to develop Alzheimer’s. If there is an increased risk, people would be treated with drugs which prevent the outbreak of the disease.

Still, the attention her company gets despite the fact that it has not yet produced a marketable drug is significant. There’s hardly a business or scientific publication that has not talked to Pfeifer. That has to do with the subject of its research: Alzheimer’s is scary. But it also has to do with Pfeifer herself, who does not fear publicity. She presents herself as a woman who knows that she stands out. Wearing a black leather jacket and a colourful top, she forms a marked contrast to the grey scientists in grey rooms which surround her. Casually, she talks about meeting Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, and asking him how he became so successful at public presentation of his products. “His answer: practice, practice, practice. He practiced his presentations thousands of times.” Pfeifer does the same. She leaves nothing to chance.

Whether her vision can be realised is still unclear. Certainly, AC Immune could do with some good news. In 2016, it listed on the Nasdaq Stock Exchange in New York and raised 70,5 Million Dollars. But since then, the stock has lost a third of its value. According to Pfeifer, that is at least partly due to the expiry of the lock-up period during which new investors are prevented from selling their stock. “And we have to publicise our brand more effectively in the United States”, says Pfeifer.

In addition, setbacks suffered by other companies in Alzheimer’s research have affected the value of AC Immune. In 2016, the company suffered a loss of one million Swiss Francs (1,06 million US Dollars), in the first nine months of 2017 the loss mounted to 25 million Francs (26,6 million Dollars). But she is not worried about that. “Our financial results are not that important. They will remain irregular until our drugs come to market”, she says.

As a woman at the head of a company, Pfeifer automatically stands out. In Switzerland, only 12 percent of top management is made up of women. “In my career, I have often been in situations where I was the only woman”, Pfeifer says. It was not easy, and she is convinced that young women today need to be assisted to reach the top. “Above all, they need one thing: positive role models.” She herself never had such a role model – and initially did not want to be one. “It went against the grain for me to be declared a role model”, she says. “But now I have realised how important that is for other women.” One of the women working for once said that she believes in her own prospect of a successful career because she can follow Pfeifer’s example.

Pfeifer is married, has no children. But she is convinced that even with a family she would have made it to the top. And that this should also be possible for women working in her company. “The times when women had to make a choice between work and family are over.”

But her decisiveness on the issue probably ignores some of its complexity. Not all women have bosses who want to promote a balance between work and family life. And Pfeifer herself had to make many sacrifices during the course of her career. “I work hard, travel a lot. My social life has suffered as a result.” But her family always had top priority, she says: “I always have time for them.”

When she was 11 years old, Pfeifer’s mother fell seriously ill. When she was 17, her father was also struck by disease. “During practically my whole childhood I was surrounded by chronic illness”, she says. “It was really scary.” Even as a teenager, existential questions had to be answered: “What did that mean for my future? Would I be able to study? How would I afford it if something happened to my parents?” At the time, she could not heal her parents. But one day, she might be able to help other people. That would be a fitting end to a long story.

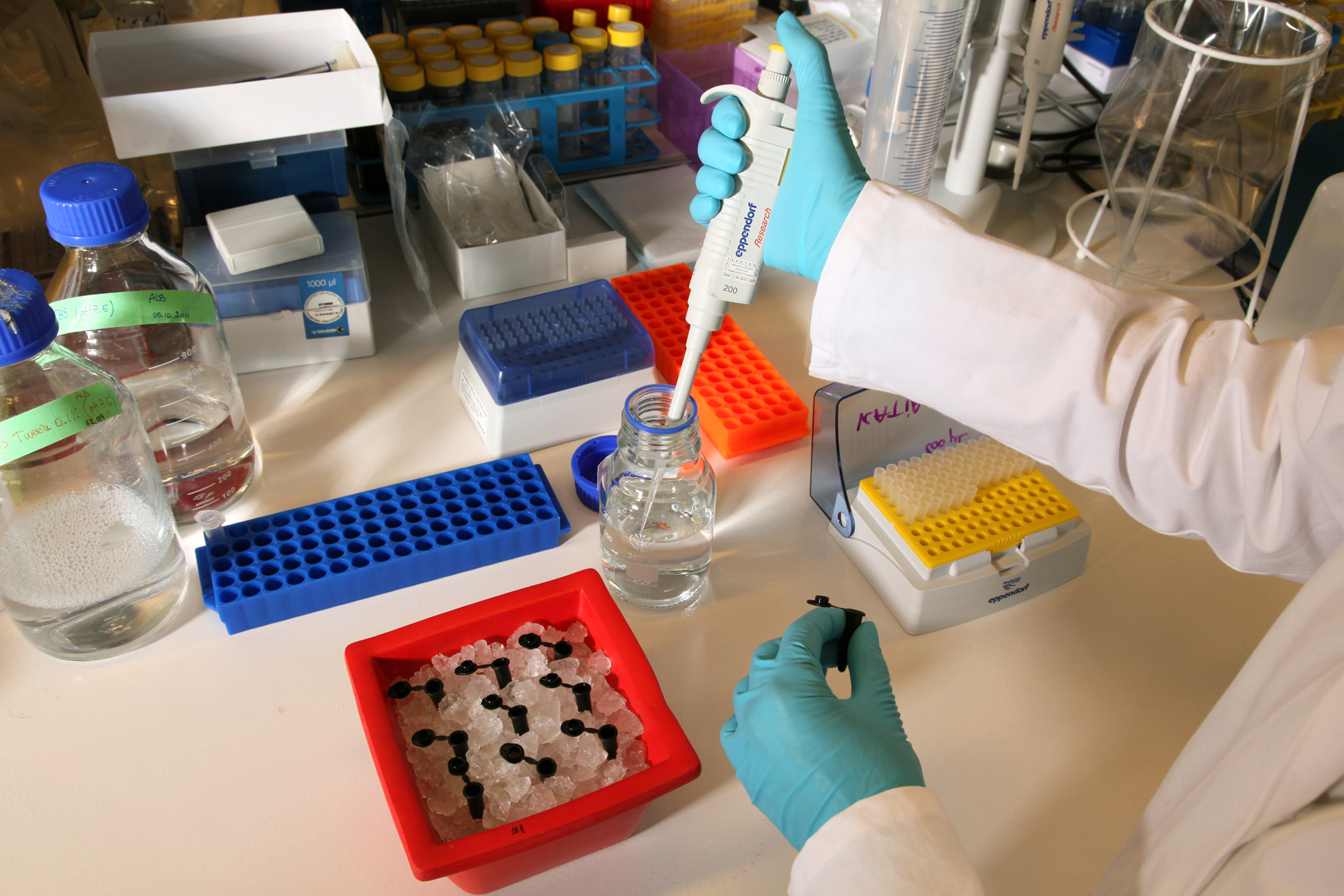

Photo: Researchers at work in the AC Immune Laboratories in Lausanne, Switzerland, where the search for a cure of Alzheimer’s Disease is in an advanced stage.

Photo Credit: AC Immune