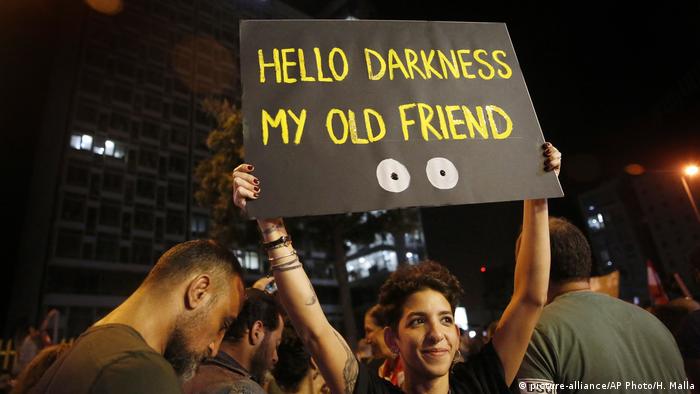

The first signs of Lebanon’s coming collapse appeared when its banks started limiting withdrawals amid nationwide protests late last year. By May it was clear the country’s financial system was crumbling. The currency was in free fall and with it the nation’s economy. Demonstrators responded with typical dark humor, carrying the Lebanese lira off in a coffin, echoing Ghanaian pallbearers.

“When people want to laugh about something, that’s because oftentimes they probably can’t do anything to change the reality,” Hussein Yassine, a writer at the Lebanese outlet The961, told DW. “It’s not just ridiculing an idea without understanding its dire consequences, but it’s one way to cope.”

#Lebanon's currency lost more than half its value since last fall. Bring in the pallbearer meme.#WorkersDay

h/t @LyesAbouJaoude

Link to original video: https://t.co/VYo6ag0P0P pic.twitter.com/fUjJGUMTgE— Kareem Chehayeb | كريم شهيب (@chehayebk) May 1, 2020

That humor has long been a marker of resilience in a country where the lira has now lost around 80 percent of its value. Food, fuel and medicine are all disappearing from the market as foreign currency to buy vital imports has evaporated.

As well as the impact of business closures due to the new coronavirus, unemployment has skyrocketed, the poverty rate is nearing 50% and the middle class is being wiped out.

French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian visited Beirut this week to discuss reforms that might have enabled a bailout, including changes to the ailing electricity sector, the modernization of some laws and a reduction the country’s public debt. But the talks appear to have failed.

This led to another joke among finance observers — that blackmailing French President Emmanuel Macron by threatening an invasion of hummus was now one of the government’s plans to end the crisis.

People have protested the Lebanese electricity company headquarters over allegations of corruption and power cuts

Lebanese barter baby formula for blankets

As well as humor, people are finding other ways to show solidarity. Supermarkets have been forced to constantly change the prices of the few goods they can still stock, and some customers hoard what food is available. In response, Facebook groups like “Lebanon barters,” set up to help facilitate the exchange of household goods such as blankets, watches and shoes for food, diapers and baby formula, have seen a massive increase in members.

By bartering, people are able to get what they need without being forced to sell belongings below their value, said Nour Haidar, one of the volunteers running the group. Users are asked not to post just requests, but also to make an offer, in order to protect their dignity.

With some hospitals and pharmacies reporting a scarcity of medicine, many group members are offering what they have for free.

“People are trying to stand up for each other. Solidarity has shown very clearly in this situation,” Haidar told DW.

‘Hunger is heresy’

But a rise in “hunger crimes” shows others aren’t coping as well.

Police are seeing “a new kind of theft that involves mainly baby milk, food, and medicine,” an unnamed security official told news agency AFP last week.

Last week, one Beirut resident said a man who wanted food for his family robbed him at knifepoint but then turned around, apologized and tried to return the stolen money, explaining he had lost his job and couldn’t pay rent, according to AFP.

“I told him that I forgave him, and then he went away,” Zakaria al-Omar told AFP. “I was scared but I also felt sad for that man breaking down in front of me.”

Two weeks ago, a man killed himself on Beirut’s main shopping street after reportedly posting his clean criminal record and a note to a tree that read: “I am not a heretic.” The quote comes from a popular song that continues, “but hunger is heresy.” A relative of the man blamed the country’s rulers for the hardship that led to his death, according to Reuters.

Refugees trapped as Lebanese look for exit

Similar tragedies have struck the most marginalized in Lebanon.

Foreign domestic workers have been forced onto the streets as employers cancelled their contracts, sometimes without pay, and many cannot find the funds to travel home. Some find shelter with charities, while others camp out in front of their embassies.

Some 50 percent of Lebanese people worry they will not have enough to eat for the month, but that number rises to 63 percent for Palestinians and 75 percent for the roughly 1.5 million Syrian refugees in the country, according to a June report by the World Food Program. While many Lebanese are trying to leave the country if they can, most refugees have no such option.

“The first opportunity I get, I’m going to leave for sure,” said Hussein Yassine in the southern city of Tyre. “It’s not easy to cope because there’s no solution on the horizon.

“It’s a very harsh reality that we’re living in right now and it’s probably going to get worse in the coming months. This is what really scares me.”

But the dark jokes will remain a staple. “In any conversation there has to be humor, otherwise it’s just considered a bad conversation by our standard,” Yassine said. “You’re always going to find humor while Lebanese are suffering.”