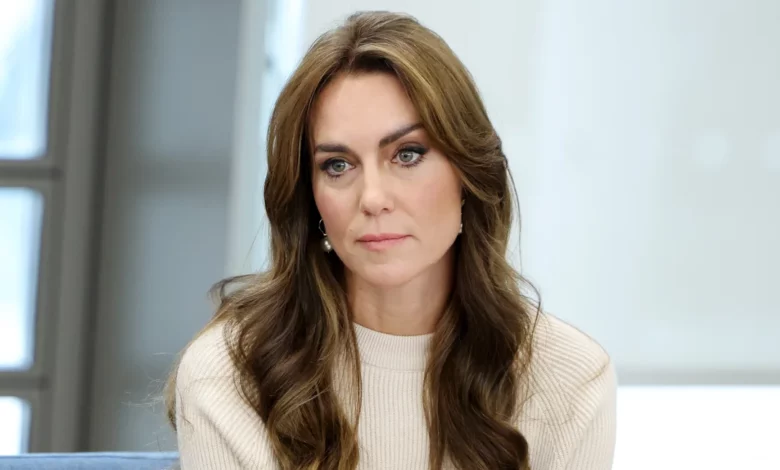

The truth, as it often is, was less strange than many had thought. After weeks of frenzied conspiracies about why Catherine, Princess of Wales, had been so long out of the public eye, she revealed the reason: She had been diagnosed with cancer, was in the early stages of treatment and had taken time to tell her young children.

For Kate and her family, the past three months have been a crisis. But for others, they may have brought opportunity.

“You had a swirling mess of speculation, which provides a great place if you’re a foreign actor and you want to get involved,” Martin Innes, a disinformation expert at Cardiff University in Wales, told CNN. “It’s the ideal situation, really.”

Innes and his research team linked 45 social media accounts posting bogus claims about the princess to a Kremlin-affiliated disinformation campaign which has previously peddled conspiracies about Russia’s war in Ukraine and French President Emmanuel Macron. The motive of such campaigns, Innes said, is to “destabilize” Russia’s Western antagonists and “undermine trust” in their institutions.

The United Kingdom’s relationship with Russia has long been mixed. The Brits have been happy to provide services for – and welcome in the wealth of – oligarchs from the former Soviet Union, despite hostilities between London and Moscow. A 2020 UK parliamentary report found “plenty of evidence of Russian interference” in its democratic processes, saying Russian influence had become “the new normal.”

The Cardiff researchers have run a large research program into disinformation since 2018, but began investigating the Kate conspiracies after seeing “unusual patterns in the traffic data” and “spikes coming out of nowhere.”

“The accounts were not making original posts themselves, but were reply-commenting to posts about the Princess of Wales story, introducing material about the Ukraine war, denigrating Ukraine, or celebrating the integrity of the Russian elections,” Innes said.

The pattern of behavior was one his team recognized from a group of Russian actors his team had studied before.

The group is referred to as “Doppelganger,” a Kremlin-linked operation that has targeted audiences in the United States and Europe, including Ukraine. It is a commercial firm contracted to run disinformation campaigns, Innes said. In late 2022, Meta – the owner of Facebook and Instagram – warned Doppelganger had been mimicking major news outlets and creating spoof articles.

Meta said it disrupted the group, but its disinformation campaigns have since grown more sophisticated. Last week, the US Treasury sanctioned two Russians and their companies believed to be part of Doppelganger, accusing them of running “a sprawling network of over 60 websites” stoking disinformation on behalf of the Russian government.

Some conspiracies may be created afresh. Earlier this month, the British Embassy in Moscow was forced to deny insensitive rumors about King Charles III which had begun to circulate wildly on Telegram and in the Russian media.

But often the group seeks to foment stories already causing division. The Kate rumors were particularly easy for the campaign to target, Innes said, because much of the Western public was already in a conspiratorial “mindset.”

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, director of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, told CNN that disinformation campaigns “always jump on issues that are engaging and divisive, and that lend themselves to making people question the credibility and trustworthiness of the information they see.” But how effective the campaign may have been, he added, is another question: “Most people come across a lot of nonsense on the internet anyway and are generally quite skeptical of all of it.”

When Kensington Palace announced in January that Kate had undergone planned abdominal surgery, the initial reaction in Britain was more shock than suspicion. But, with every week she spent out of the public eye, speculation swirled further.

But amateur sleuthing on social media only tipped into full-blown conspiracism when the palace released a photograph of Kate and her three children on Mother’s Day. The photo, which should have put an end to the rumors, instead fueled them. Members of the public swiftly clocked several discrepancies in the image including blurs on a sleeve cuff and a zipper out of joint.

Within hours, multiple global news agencies had recalled the image from circulation, citing manipulation concerns. The following morning, Kate issued a mea culpa: “Like many amateur photographers, I do occasionally experiment with editing.”

Anna George, who researches online disinformation at the Oxford Internet Institute, told CNN, “Russian disinformation campaigns like to sow confusion about who to trust,” and suggested the debacle may have provided the Kremlin grounds to accuse British institutions of spreading fake news.

The Yale historian Timothy Snyder has long argued that Russian President Vladimir Putin’s way of maintaining power is through “strategic relativism.” Unable or unwilling to make his own country better through domestic policy, he settles instead for making other countries look worse, bolstering Russia’s standing by weakening others.

The Russian Foreign Ministry leapt on the faux pas with Kate’s photo, saying the British media and political system had “merged” to create “an ecosystem of lies.”

In a barbed statement, the ministry said the princess’s prolonged absence from public life “once again highlighted the rotten nature of the British political establishment, based on its desire to completely control public opinion… through mass media manipulation and fake news.”

In the days after the Mother’s Day photo, Kate was seen with her husband, Prince William, at a farm shop in Windsor near their home on March 19.

Innes said he and his researchers saw a sudden flurry of activity the same day – primarily on X, formerly Twitter – in a way he said was “absolutely consistent with Doppelganger.” All of the accounts his team identified had similar names, were created at the same time, had very few followers and acted in a coordinated way, he said.

“The 45 accounts all either had this naming convention of either a letter A start or a letter B start, like ‘Aardvark56,’” he said, which was “sufficient to be able to validate the claim that we know who is behind this.”

The timing of the Kate conspiracies was also propitious for the Kremlin – coming just as Putin secured a fifth term in power in a stage-managed election devoid of credible opposition. The bots, Innes said, piled onto posts about Kate’s health with comments talking up the legitimacy of the Russian vote.

A conspiracy striking at the heart of the British establishment coming at a time beneficial to Russia created a “goldilocks zone” for Kremlin-linked actors, Innes said.

“Tactically, what they were trying to do was to get their messages about the Russian elections and Ukraine into the Western media ecosphere. But why this was such a good story for them was because it allowed them to hit their strategic aim… to destabilize the UK and its Western allies.”