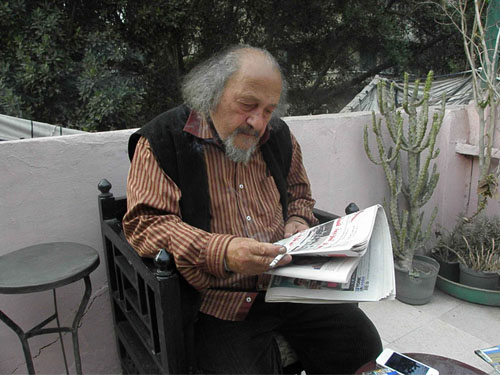

“Missing Pieces,” Karim Bakry’s project on exhibition at Mashrabia Art Gallery this month, began as a response to a request from a gallery in Gothenburg, Sweden that he, as an Egyptian artist, create a work to comment on the political tumult barreling through his home country.

“They invited me there for a show, and they said that I should do something related to the revolution, because I am Egyptian,” says Bakry.

Such demands have exhausted Egypt’s artists with their essentializing premises and lack of interest in what it actually means for an artist to respond to a political event. But Bakry met the challenge, and perhaps unsurprisingly created something slight and gimmicky, constructed of a collection of one-to-one metaphors that come together to re-present familiar imagery in an only vaguely unfamiliar way.

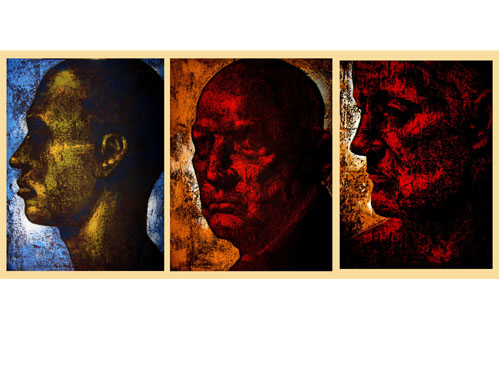

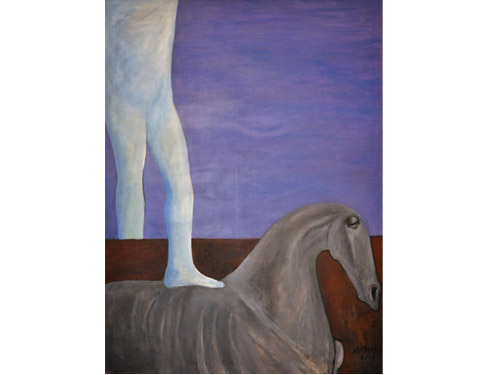

Bakry’s installation, which forms the core of the exhibition, recreates what he originally constructed in Gothenburg on a smaller scale. It is composed of cardboard boxes, stacked together in a dark room to appear reminiscent of a cityscape. Images of protest and street violence from the past year that Bakry himself captured are projected onto the cardboard boxes, which form an unorthodox screen. The images cycle through a slideshow and appear on the boxes in a fractured and refracted form, random elements of the images pulled out momentarily: a hand or a face lifted from a jumble of people, a scene of fire or flags turned abstract.

Although it is interesting to see the way in which the images and their three-dimensional screen interact, the work is not put together with any sense of selection or intention. The images are not chosen for the way they interact with the boxes, for their specific visual effect, but simply because they are the images that Bakry has of street protest and unrest in Egypt. Sometimes the effect is surprising and interesting, and sometimes it is simply a jumble of projection and cardboard.

But a viewer is unlikely to spend much time looking at these images in any case, because Bakry presents his work as such a simple, straightforward metaphor, that it makes the piece itself feel like an afterthought. As the title, “Missing Pieces,” suggests, this construction is meant to represent the fractured and incomplete nature of the revolution itself.

“In the beginning, in January, there was great continuity, and then everything fell apart,” says Bakry.

Marwan El Gamal writes in the text accompanying the exhibition, “Familiar images are projected on an unfamiliar format; unlike a screen, these boxes cannot display a whole image, leaving unmarked spaces between each, such as the missing pieces for a successful revolution.”

The statement has the unfortunate effect of making the work itself seem irrelevant, so completely does it explain away every formal element of the installation into a forgettable conceptual framework.

Bakry’s work is a hodgepodge of ideas, offered up somewhat unceremoniously via a random selection of aesthetic constructions that directly represent them. The boxes, in their blocky brownness, effectively recall the jumbled Cairo skyline. But there are other ways to achieve this formal similarity.

Why did Bakry choose cardboard boxes if his primary intention was to present images broken into pieces? The artist could have employed pedestals or hanging panels, which would neutrally create the same effect, without introducing the connotations of a cardboard box. The material is specific but not in a way that contributes to the piece, creating a sense that the installation was assembled without significant reflection. Bakry says that he intentionally chose this material in order to reference “consumerism and waste,” but even within the confines of the work’s limiting conceptual framing, it is unclear what commentary is being made on consumerism, except for recognizing that it exists, or how this has anything to do with the representation of the unfinished and fractured revolution.

But, speaking of consumerism, Bakry’s installation takes up only one section of Mashrabia’s space, and the remaining space is filled in with a collection of photographs of Bakry’s previous installation in Gothenburg. The images do capture how a larger, more carefully assembled version of the installation at Mashrabia can create some very interesting and even beautiful visual moments. But the images, mounted on heavy frames so that they have the heft of paintings, are clearly on display for only two reasons: to fill space, and to present the public with something they can buy.

While there is nothing wrong with a gallery finding a way to make money while exhibiting the kind of work that cannot be sold, it does not seem necessary to present these works as though they are independent artworks themselves, when they are quite clearly simply documentation of an installation.

While it has its redeeming moments, what generally plagues this exhibition is an inherent laziness in both concept and form, and it is unfortunate that this kind of trite, politically opportunistic work is still appearing in Cairo, particularly in such a generally consistent gallery as Mashrabia.

"The Missing Pieces" runs until 18 June at Mashrabia Art Gallery, 8 Champollion St., Downtown, Cairo.

Photos courtesy of Mashrabia Art Gallery