Shizugawa, Japan — An American helicopter crewman shouted above the din of the rotor: "What do these people need? Do they need food? Do they need medicine?"

The answer — one week after an earthquake and tsunami wiped out much of Japan's northeast coast — is: They need everything.

Aid has started trickling in, but much of it appears ad hoc and many survivors remain isolated and cold and are fending for themselves.

Two American military helicopters touched down on a hilltop above this flattened town Friday with boxes of canned beans and powdered milk for a community center that has become a shelter for those who lost their homes.

But blustery snow, fuel shortages and widespread damage to airports, roads and rails have hampered delivery of badly needed assistance to more than 400,000 survivors trying to stay fed and warm, often without electricity and running water in hastily setup shelters in schools and other public buildings.

A magnitude-9.0 earthquake struck offshore on 11 March, creating a tsunami that swept over low-lying areas, carrying boats, cars and even buildings with it and destroying nearly everything in its path. More than 6500 people are confirmed dead so far, and another 10,300 are missing.

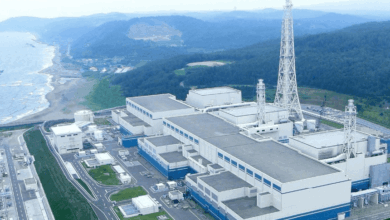

The disaster also damaged a seaside nuclear power plant, which remains in crisis as workers struggle under dangerous conditions to prevent a meltdown and major radiation leaks.

In Hirota, survivors at one shelter are getting water from wells and mountain rivers. Helicopters have delivered some food, but not much. So far, they have instant noodles, fruit and bread. Companies and residents unaffected by the disaster have donated bedding and blankets.

Kouetsu Sasaki, a 60-year-old city hall worker, said the survivors still need gas, vegetables, socks, underwear, wet wipes and anti-bacterial lotion. There is some medicine, but not enough.

"We could be living like this for a long time, so all we can do is stay in good spirits," he said. "People here aren't angry or frustrated yet…But it's a big question mark whether we can keep living like this for weeks or months. I try to concentrate on what I need to do this morning, this day, and not think about how long it might last."

The community has been left largely to fend for itself.

When a fire broke out in the rubble, survivors ran from the shelter to put it out with seawater, said Hiroyoshi Murakami, 64, a retired tuna boat radio operator who is volunteering at the shelter.

"The thing we need most is gas," he said. "It's all going to official vehicles. Without gas, we've got no cars. Without cars, we've got no way to go to the hospital. We can't go to places where we could use the phone and communicate with the outside world."

The US military, with 50,000 troops based in Japan, is helping the relief effort, but snow has limited helicopter flights, and American aircraft are also under orders to skirt the area around the nuclear plant to reduce the risk of radiation exposure.

"It's frustrating," said US Navy rescue swimmer Jeff Pearson, 25, of Amarillo, Texas. "But we're doing all we can do. I think we are going to be able to get much more involved very soon."

His helicopter crew, based on the southern Japanese island of Okinawa, was heading farther north from Japan's Jinmachi Air Base in Yamagata city.

A 24-vehicle US Marines convoy reached the base Friday, where the Marines will run a refueling hub, move supplies by road and provide communications support.

Also Friday, Sendai airport was declared ready to receive aid deliveries on jumbo C-130 and C-17 military transport planes. The tsunami had flooded the tarmac, piling up small planes and cars and leaving behind a layer of muck and debris.

"The airport in Sendai is now functional," said Japanese Lt. Col. Hiroya Goto, a military doctor acting as a liaison for the US-Japan military mission. "That's the biggest city that was hit, and now that the runway has been cleared, we expect a lot of help to start coming in."

At the community center in Shizugawa — an area of Minamisanriku town — food is coming from the local government and area volunteers and groups. Survivors eat twice a day. A mobile operator set up a cell phone tower on a truck outside the center.

Koji and Yaeko Sato, husband and wife, sat on the floor of the shelter beside a window where the names of the dead and missing are listed. Their home is gone; the tsunami left only a few large buildings standing. Their car is undamaged, but they have no gas.

Koji, 58, is a carpenter. He usually builds homes. This week, for the first time in his life, he is making coffins — 30 in all working with three others.

Asked what difficulties they are facing, he said: "I haven't had time to think about it. All I have been doing is making coffins."