Its main battlegrounds are far away and its true influence hard to judge, but the Islamic State's black banner is attracting the attention of jihadists in Africa, particularly in Nigeria.

IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi's so-called caliphate is based in Syria and Iraq and draws most of its recruits from the Middle East, North Africa and Europe's immigrant communities.

But the group's rapid rise to the top of the global jihadist movement, displacing Al-Qaeda as a source of inspiration, has had an echo south of the Sahara, where several insurgencies are underway.

Outside observers see the Islamic State's influence, for example, in the tactics, rhetoric and even online media presence of the Boko Haram rebels of northeast Nigeria and neighboring border areas.

"There are no direct operational contacts," said Peter Pham, head of the Africa Center at the Atlantic Council, a Washington think tank.

"But it is quite clear that Boko Haram is paying attention to the IS and the IS is paying attention to Boko Haram."

Jacob Zenn, an African specialist at the Jamestown Foundation, said Boko Haram had initially received backing from Al-Qaeda's regional offshoot Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.

"It has more recently begun to model its ideological and military doctrine after the Islamic State and, in turn, has started to receive recognition from the Islamic State," he told AFP.

Both experts cited public statements from Baghdadi and Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau showing direct inspiration and even a cross-fertilization of ideas.

One month after Baghdadi declared his caliphate in Iraq and Syria in July, Shekau pledged his support.

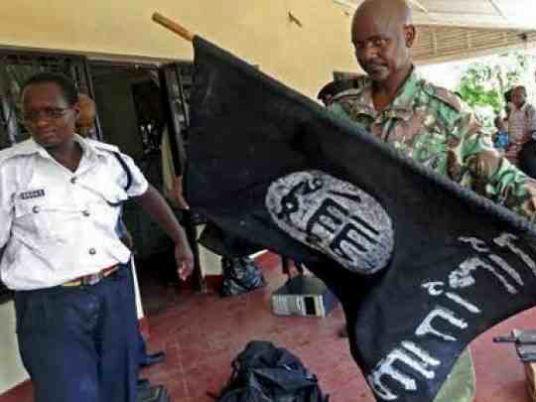

– Jihadist banner –

"Boko Haram kidnapped those famous schoolgirls," Pham said, referring to the 276 teenagers captured by the group from their school in Chibok, in an attack that triggered global outrage.

"When IS kidnapped the Yazidi girls, if you look at their statements, they actually cited Boko Haram kidnapping the Chibok shoolgirls," Pham said, citing the jihadist persecution of an Iraqi minority group.

"Boko Haram controls now between 20,000 and 40,000 square kilometers (7,700 to 15,400 square miles), 10 local governments. They feel strong," he said.

"They use heavy equipment, they parade with tanks taken from the Nigerian army flying the black flag, like they saw on IS videos. IS presents a compelling model. Al-Qaeda is the brand of yesterday."

Just as the IS has adopted the trappings of a state on its territory — a first stage in its goal of uniting Muslim lands under its jihadist banner — Boko Haram is moving on from raids to holding ground.

And a new generation of jihadists have turned away from the lengthy online sermons of Osama bin Laden's successor Ayman al-Zawahiri and to the slick propaganda videos of the Islamic State.

"These supporters of IS are not necessarily taking orders from IS central," said Zenn.

"But they may justify their own attacks and operations on the grounds that the IS organization is doing the same, and vice-versa."

For example, he said, a Boko Haram attack on a Shiite religious procession in the Nigerian town of Yobe was an attempt to stir Iraqi-style sectarian strife and appeal to Sunni supporters.

Former CIA officer Michael Shurkin, now with the Rand Corporation, said the IS state-building agenda would win more support in Africa than Al-Qaeda's bombing campaigns.

"It's governing a place," he said. "As a symbol, it's very powerful and very dangerous. IS itself, I don't know exactly how dangerous they are, except for people who live in Syria, Iraq or Lebanon.

"But… they can inspire and motivate perhaps to a greater extend than AQ has ever motivated people. Al-Qaeda is negative, about smashing thing, IS is also smashing things, but building something.

"IS has effaced the colonial boundaries, in a very concrete way."

Groups like Nigeria's Boko Haram or Mali's Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) already have local recruiting grounds. The IS model could make them hard to beat.

"If the US war on terror has accomplished anything, it's stuffing Al-Qaeda into a box. It's very different with IS," said Shurkin.

"You can go after a specific organization. The United States is very good at that. You can collect phone calls, hit them with Predator drones.

"But if it's more than an organization, if it's something larger than that, a movement, what can you possibly do to stop it? I don't know. That's the real power of IS… How do you fight an idea?"