Abdel Rahman Yusuf faces a unique political challenge: how to mount a Western-style grassroots political action campaign under traditional Arab-style restraints that make independent political activity a risky prospect.

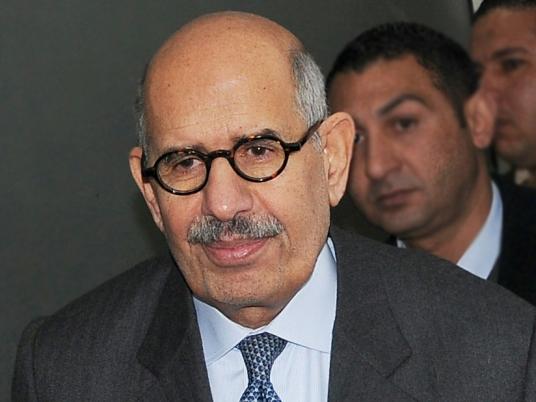

Yusuf, the son of popular television imam Sheikh Youssef el-Qaradawi (although he doesn’t advertise the fact), is one of the main point men for the next stage of Mohamed ElBaradei’s campaign for sweeping constitutional and democratic reform.

In the coming months, Yusuf and “several thousand volunteers” plan to carry out the crucial grunt work, gathering signatures for a nationwide petition aimed at demonstrating ElBaradei’s massive popular appeal.

The signature campaign is “our number-one priority right now,” said Yusuf, coordinator of the Popular Independent Campaign to Support the Nomination of Mohamed ElBaradei–otherwise known by the moniker "ElBaradei 2011."

And while he’s careful not to make any predictions, or state definitively how many signatures would be considered a success, Yusuf is quick to stress how important the signature drive is to the future prospects of the ElBaradei reform campaign.

“How we do on that will, to a large extent, determine what comes next,” he said. “There’s a big difference between 20,000 signatures and half a million.”

The signature campaign centers around the National Association for Change’s seven-point list of reform demands. These include ending Egypt’s longstanding state of emergency; establishing electoral supervision by both local judges and international monitors; allowing Egyptian expatriates abroad to vote; setting limits for presidential terms; and eliminating official obstacles to an independent presidential candidacy. All told, the changes demanded would require three separate articles of the Constitution to be rewritten.

Sitting behind the desk in his modest downtown office, Yusuf waves around several pieces of white printer paper containing the latest draft of an instruction manual he plans to distribute to volunteers. The final version should be printed and passed out by the end of the month–which, he says, is when the full-scale signature drive will begin in earnest.

Topping the list of instructions will be guidelines on how to gather signatures without being arrested or provoking confrontations with the authorities. In a Western political context, none of that would be necessary–volunteers would be able to operate freely on public streets, in social hubs or at work places. But Yusuf seems keenly aware that none of these options will be available for this particular signature drive.

While the regime has so far been reluctant to directly attack ElBaradei or restrain his activities, Yusuf and his young volunteers represent much softer targets. Already, one publisher who put out a pro-ElBaradei book has spent a night in police detention. As Yusuf puts it, “The streets belong to [the regime].”

That’s why he’s including detailed instructions on how to gather signatures while staying off the radar.

“If you show up on the factory floor asking for signatures, two things will happen,” he said. "You [will be fired or arrested] within two days, and everyone else will see what happens to you and will become more afraid to get involved."

Another crucial instruction: how to politely and persuasively respond when a citizen says they support ElBaradei’s ideals but are afraid of getting into trouble. Yusuf said he’s already warning his volunteers not to criticize or belittle people’s fear of the government.

“We respect the fear of the people. Their fear is justified. After 30 years under martial law, they’re right to be afraid,” he said.

As the signature campaign heats up, ElBaradei and his organization are already fending off critics eager to declare it a failure, or to paint his campaign to rewrite the rules of Egypt’s political game as a Quixotic pipedream.

“His campaign is populist so far, because he does not have a solid program for change and depends only on his resume,” said Khalil al-Anani, a political scientist at the semi-official Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies who is currently serving a fellowship at Durham University in England. “I think he will lose a lot of his prestige with time.”

And while Anani doesn’t believe the campaign will succeed, he does see ElBaradei’s ultimate impact on the Egyptian political arena as positive.

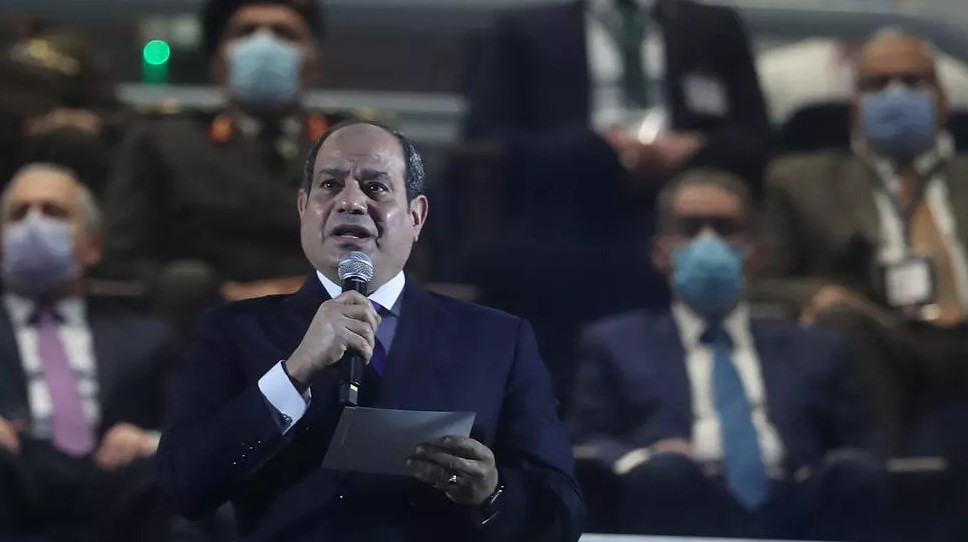

“I doubt that ElBaradei will be the savior for Egyptians from the Mubarak regime,” he said. "However, he is playing a vital role in pushing the wheel of change forward."

Mostafa Elwi Saif, chairman of Cairo University’s political science department, said ElBaradei remained an “elitist” phenomenon and is “not well known in the countryside.”

Saif, a member of the ruling National Democratic Party and the Shura Council (the upper house of parliament), said he doesn’t believe ElBaradei had time before next fall’s presidential elections to gather sufficient support for a constitutional rewrite that would allow him to run as an independent.

“It seems the door to an independent candidacy is not open,” he said. “Dr. ElBaradei will have to take a decision whether to join one of the established political parties or not.”

But that’s exactly what ElBaradei and his supporters have vowed not to do.

According to Yusef, the entire message of ElBaradei’s campaign is that the current political game is rigged. Joining a licensed party, “would be the biggest favor [ElBaradei] could do for this regime,” he said. “Once you join a party, you’re on the stage. Well, who built the stage? Who wrote the script?”