India’s foreign minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar on Monday said the agreement on military patrolling in certain areas brought the situation back to where it was in 2020 prior to a deadly border clash that year, thus completing the “disengagement process” with China.

Beijing later confirmed on Tuesday that the two sides had “reached a solution” following “close communication on relevant issues of the China-India border through diplomatic and military channels.”

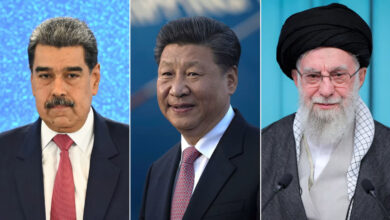

The announcement has been widely seen as setting the stage for talks between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who are attending a three-day summit of BRICS nations in southwestern Russia’s Kazan.

India’s Ministry of External Affairs confirmed the leaders would meet on Wednesday. The sit-down is expected to be Xi and Modi’s first formal talks since before the 2020 clash, which has left a lasting strain on the countries’ relationship. Beijing has yet to confirm the meeting.

In their statements on the border arrangement earlier this week, neither side released full details of what was agreed or details of how it would be carried out.

Both India and China maintain a significant military presence along their 2,100-mile (3,379-kilometer) de facto border, known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC), which has never been clearly defined and has remained a source of friction since a bloody war between the two countries in 1962.

The clash four years ago along the disputed border between Indian Ladakh and Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin brought the first known fatalities in more than four decades – with at least 20 Indian and four Chinese soldiers killed.

In a rare, informal meeting at last year’s BRICS summit in Johannesburg, Xi and Modi agreed to “intensify efforts” to deescalate tensions at the contested border. Chinese and Indian negotiators held the 31st round of border talks in late August.

While an agreement on further disengagement on the border appears poised to be a significant step in what has been a sore point among other frictions in the China-India relationship, observers said more details were needed to understand the scope of the arrangement and what concessions may have been made.

‘A positive development’

The violence in 2020 was followed by a process of disengagement and border talks, but friction points have remained, including areas where both sides previously patrolled but have since become so-called buffer zones.

Within India, the situation had also raised questions over whether the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was using the buffer zones to further push back the areas within which Indian forces can patrol. India’s Ministry of Defense has previously denied the loss of any territory during the standoff.

Speaking about the new agreement at an event hosted by Indian broadcaster NDTV Monday, India’s Minister of External Affairs described how after the 2020 clash the two sides had “blocked” each other in certain areas.

“What has happened is, we have reached an understanding which will allow the patrolling … the understanding, to my knowledge, is that we will be able to do the patrolling which we were doing in 2020,” Jaishankar said.

“It is a positive development. I would say it is a product of a very patient and very persevering diplomacy,” he said, adding that the consequences of the agreement on the two nations’ relationship had yet to be seen.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian on Tuesday said Beijing “positively evaluates” the “solution” reached and would “work with India to implement the above solution,” without providing further details. Lin’s comments were made during a regularly scheduled media briefing.

It’s not clear why the two sides did not release a joint statement on the issue, and observers say the governments need to release more details of the arrangement before it can be fully evaluated.

Manoj Kewalramani, who heads Indo-Pacific studies at the Takshashila Institution research center in the Indian city of Bangalore, said a restoration of patrolling rights would be a “significant starting point” for normalization.

However, even with that restoration, there are other steps that would need to be taken in a long process along the disputed border.

“There are many other issues of de-induction and de-mobilization of troops on both sides; infrastructure that has been built, etc. These issues will take time,” he said.