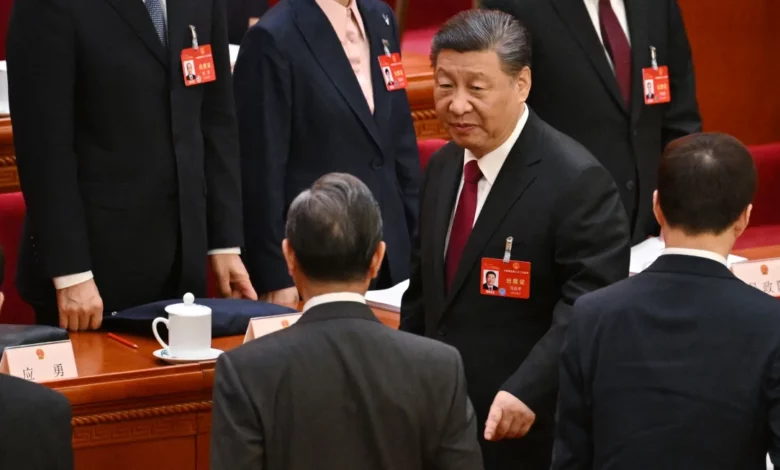

No more face masks or social distancing rules. For the first time in four years, thousands of delegates attending China’s biggest political event of the year were able to mingle and sip tea like the old days in the sprawling foyer of Beijing’s Great Hall of the People.

While some Covid testing requirements remain in place, on the surface, everything else seems back to pre-pandemic normal at the annual meetings of the rubber-stamp national legislature and China’s top political advisory body.

But this year’s event also provides a fresh window into persisting controls and increasing opaqueness of the political system under leader Xi Jinping, who has prioritized security and strengthened the ruling Communist Party’s grip over everything – including the so-called “two sessions” itself.

More than ever, Xi is looming large over the gathering, which had traditionally been a stage for the Chinese premier and the central government to shine.

Beijing sent what observers say was a strong signal of that a day ahead of the opening of the National People’s Congress earlier this week – announcing that it was scrapping an annual press conference led by the premier – a three-decades-old political tradition that has long been a key landmark of the meeting, typically televised and highly anticipated.

A government representative claimed the change was due to other opportunities for interviews.

But observers saw one fewer chance for the world’s media, international observers, and Chinese citizens to get first-hand insight into the thinking of the country’s nominal No. 2 official, who is charged with running its economy – and one more move for Xi to cement his control over the official narrative.

“The press conference is typically the only channel for any senior official in China to have a direct communication with the outside, especially with foreign media,” said Liu Dongshu, an assistant professor focusing on Chinese politics at City University of Hong Kong.

“If you think about our image of past premiers, a lot of our understanding of their personality, reputation, authority is actually based on what they said in the press conference … removing this channel for the premier is consistent with the change that Xi Jinping is the only one that they want to signal to the outside (and) everyone else … is to some extent just a follower,” he said.

While the press conferences themselves are carefully stage-managed, they have in the past provided moments for premiers to inject their own persona and views – or make departures from official lines, providing rare insight into thinking or even debates among China’s elite leaders.

Former Premier Li Keqiang famously noted in his 2020 conference that, as Xi hailed China’s efforts in in poverty alleviation, 600 million people in the country still had a monthly income of just 1,000 yuan ($137).

Current premier and Xi protégé Li Qiang, who was expected to lead the closing event this time, however, has not appeared to have such an inclination. He used his first and likely last press conference last year to highlight the prominence of the Communist Party over the state government.

And on Tuesday, Li mentioned Xi’s name 16 times when delivering the government’s work report to delegates. “We owe our achievements in 2023 to General Secretary Xi Jinping, who is at the helm charting the course, and to the sound guidance of Xi Jinping Thought,” Li said.

That only makes it all the more telling that the conference has been scrapped, especially in an environment when Beijing is aiming to bolster business confidence, observers say.

“It is a gesture to show that the government cares about the perception of the outside and trying to establish an image of being open, being transparent,” said Liu in Hong Kong. “Keeping the press conference may not give us something new, but removing it is a bad signal … in terms of transparency and keeping outsiders confidence in China’s commitment to its opening up.”

Changhao Wei, a fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center of Yale Law School, noted an NPC spokesperson had strongly implied that the premier’s presser wasn’t necessary because the news conferences attended by other government officials would be adequate substitutes.

“I don’t find this reason particularly convincing because this year the NPC scheduled only 3 themed press conferences, compared to 13 themed press conferences in 2019 attended by not only administrative officials, but those from the courts and the legislature as well,” he said.

The axing of the premier’s press conference came alongside a shortening of the “two sessions” overall – first imposed during the pandemic to prevent the spread of Covid.

The move also reduces opportunities for journalists to ask questions of delegates or government officials, either in designated briefings or doorstepping them as they enter and exit the building.

But even the nature of those encounters, which in recent decades saw reporters able to grab telling comments from officials, has changed – as delegates are widely seen by reporters as much less willing to say too much in the current political climate.

Heavy security

Meanwhile, even as Covid-19 curbs were lessened, signs of heavy security, though typical for the “two sessions” period, were visible throughout the political heart of the city.

For event attendees, usual security checks at certain entry points were augmented by facial recognition scanners that determined if people were cleared for entry.

In Tiananmen Square’s subway stations and nearby streets, where security is tight regularly, police presence was heavy, with security vans parked roadside and officers holding muzzled police dogs monitoring crowds of people making their usual commutes.

Traffic slowed due to checkpoints on surrounding streets, with security officials even stopping and checking IDs of some cyclists riding on a major throughfare along the square. In surrounding neighborhoods, red-clad community “volunteers” were also out in force keeping an eye out for any suspicious activity.

Even mail was getting a stricter treatment, with China’s postal authority issuing a notice late last month outlining a system of double inspection for incoming packages during the two sessions period – with residents taking to social media to complain of delays.

Tightened security is typical of the political gathering and many around the world – but apart from concerns about safety, Chinese authorities during major events are typically on high alert for showings of dissent and are known to ramp up repressive measures to ensure that dissidents or people petitioning the government stay silent.

As public frustration mounts around financial hardships linked to an ailing economy – and the Communist leadership seeks to block negative narratives and project confidence, officials this year may be particularly wary of any showing of discontent.

Xi’s government already had to face large-scale demonstrations once – when rare protests broke out across the country in late 2022 as anger boiled over about on-going Covid-19 controls.

That movement followed a single act of protest in Beijing before a major Communist Party meeting, when an unidentified person hung a banner from a highway bridge protesting Xi and his Covid-19 policies – prompting heighted security on overpasses throughout the city in its wake.

Many measures around Tiananmen this week were expected to last only for the gathering.

But when asked whether open access into an area near the square would return following the event’s close, one security guard responded: “you’ll have to see.”